|

| A painting of Billy the Kid, Dick Brewer, and the Regulators by Andy Thomas depicts Bonney in the outfit he wore in the only totally confirmed tintype image of him. |

Note—The tale of Billy the Kids career grew like Topsy and will be told in two entries, stretching series to four posts.

A cradle Gaelic speaker, the real Billy the Kid spoke English with a decided New York slum accent—imagine a Bowery Boy on a horse. Once in New Mexico he quickly learned Spanish and soon spoke in the local dialect almost like a native. Unlike many Gringo adventurers he held the Mexican community in high regard, made many close friendships, romanced the senoritas—and may have left a son born after his death by one of them. That community returned the affection and often offered him protection when he was on the run from rival gunmen or the law.

In fact he was said to be unfailingly polite, soft spoken, noted for seldom cursing in a country where every second word was often a profanity. Of course he was also a remorseless killer.

Henry McCarty was born on or around September 17, 1859 to Irish immigrants Patrick and Catherine McCarty in New York City and suitably baptized at the historic Church of St. Peter in Southern Manhattan. After Patrick died the family moved to Indianapolis where Catherine met and took up with William Henry Harrison Antrim, an American of Scotch-Irish lineage. The family moved with him to Witchita, Kansas in 1870 and on to Santa Fe, New Mexico in 1873 where his mother married Antrim in a Presbyterian service. It is unclear if they ever had a legal civil marriage before that. About that time the boy began using the name Henry Antrim—the first of several monikers which have confused his identity over the years.

The following year his mother died leaving him as an orphan to shift for himself. He put up at a local boarding house in exchange for doing chores but was apparently so poorly fed he was arrested for stealing food. Released from that petty offense, he and a pal knocked over a Chinese laundry ten days later and made away with clothing and a pistol—likely the first firearm he ever had. He was quickly caught and jailed but managed to escape. An item on the escape in the local paper was the first press notice he ever got. He found his stepfather, who had left Santa Fe, and stayed with him for a short while until the two quarreled and he ran away taking Atrim’s clothes and gun.

Henry was soon in southern Arizona where

like many homeless lads he took up cowboying. After learning the necessary skills, he fell in

with former Cavalryman and horse thief, John R. Mackie and the

pair began stealing horses on and around Camp

Grant. Still too young to raise a beard and not yet full grown, the boy got to be called Kid Atrim by his confederates

and those to whom he sold his stock.

With

money in his pocket now to spend, he took to hanging out at saloons. Not

a heavy drinker, he spent his time gambling with the usual mixed results. On August 17, 1877 found

himself being bullied by a hulking blacksmith named Francis “Windy” Cahill in an

establishment at Bonita near Camp

Grant. In a tussle the two fell to the

floor with the larger man on top

of Henry as they wrestled for his pistol.

The Kid got it first and shot Cahill who died of his wounds two days later.

It was the boy’s first known kill.

Everyone agreed it was self-defense but

a local Justice of the Peace arrested

him for trial by Territorial authorities. He was held, briefly, in the Camp Grant stockade but once again managed to

escape on a stolen horse.

He

headed across the rugged, mountainous

dessert country hoping to get to New Mexico. But he rode into Apache territory where he was stopped,

relieved of his horse, stripped of his boots and weapons and set free to walk to safety if he could survive. He barely did. After days in the wilderness suffering hunger

and thirst, his bare feet bloody stumps he stumbled into the remote ranch of John Jones in the Pecos Valley near Ft.

Stanton. Jones was a member of the Seven Rivers Warriors, a gang of horse

thieves working both sides of the border.

Jones’s wife Barbara tenderly

nursed him back to health. For which

he was eternally grateful. When he recovered sufficiently he slept on the ranch house roof to keep

watch against Apaches who were raiding

in the area. He loved the family and his

attachment even continued when John Jones ended up on the other side of the Lincoln County War. Jones’s murder at the hands of a fellow gang

member would be bloodily avenged by

the Kid in yet another escape.

When

he recovered his health The Kid made

his way to an abandoned Cavalry

post, Apache Tejo where he joined a

large and well organized group of rustlers preying mostly on the vast herds owned by John Chisum in Lincoln County. Chisum was not a man to be crossed. After Kid

Atrim was recognized and his name associated with the gang in a newspaper

in Silver City, he drifted away from

that gang and began using the name William

H. Bonney to throw off his enemies. Kid Atrim was on his way to becoming Billy the Kid.

|

| English born rancher and businessman John Henry Tunstall became young William H. Bonney's employer and surrogate father figure. |

Back

in Lincoln County, Billy hooked on with English

born rancher and merchant John Henry Tunstall who on multiple fronts was challenging a trio of Irish businessmen

ranchers—Lawrence Murphy, James Dolan, and John Riley—who had dominated

the County economically and via a political machine for ten years.

|

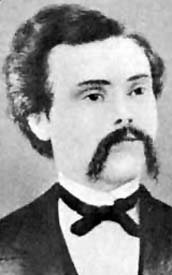

| James Dolan and Lawrence Murphy, to of the triumverant of Irish ranchers and businessmen who largely controled Lincoln County. |

Tunstall was assembling a number of tough

young cowboys and adventurers known to be handy

with their guns and fists as a

defense from the large number of hands his rivals could muster and the corrupt sheriff, William J. Brady who

they controlled. Tunstall apparently took a special shine to William Bonney and treated him with not only kindness, but respect. Billy, always intensely loyal to those who gave him a hand quickly grew to love

Tunstall who he came to regard as a father

figure.

|

| Alexander McSween took over after Tunstall's murder. |

Tunstall

had a partner, lawyer Alexander

McSween,

who was also a close associate of

John Chisum. So just a few months after

Kid Atrim

was raiding his herds, the powerful Chisum became a de facto ally of Tunstall

and while not an active participant

in the feud the cattle magnate offered quiet support and sometimes safe

haven for Tunstall followers. It is

unclear if he ever knew that Kid Kid Atrim and Billy the Kid were the same person, but a man like Chisum tended to know everything he needed to know and then some.

What

had been a political feud, a few dust ups between the hands on either

side on the range and in the saloons, and maybe a few long lariats tossed over the wrong steers, took a far deadlier turn when James Dolan

claimed that McSween owed him $8,000 but convinced a corrupt judge to order the attachment

of $40,000 of Tunstall’s livestock and property to secure it. As Tunstall got

word that Sheriff Brady and a posse

was ready to move he sent his most

trusted hand—Billy—to hide eight prize horses on the ranch where they could

not be found. Meanwhile he rode out to personally intercept the Sheriff.

On

February 18, 1878 Tunstall and the posse found each other. One of Brady’s men shot him in the chest, knocking him wounded to the ground. Another walked over the prostrate man and executed

him with a bullet to the head.

When

he heard the news, Billy was inconsolable

and vowed revenge. But he did not immediately act. On the advice of McSween, a lawyer, Bonney and his close friend Dick Brewster swore affidavits against

Brady and his posse for murder and

obtained warrants for their arrest

from Lincoln County Justice of the Peace

John B. Wilson. On February 20 the

pair and others attempted to arrest

Brady but instead were surprised and

themselves arrested by the posse.

Deputy Federal Marshal Robert A. Widenmann, a friend of Tunstall and Bonney, accompanied by troopers from

Ft. Stanton, arrested the jail guards and freed the prisoners. Billy and Brewster organized other

Tunstall employees and friends at that time into the Regulators who

considered themselves legitimate lawmen enforcing a legal order. Some of them, including Bonney, apparently

even obtained Territorial bailiff badges.

On March 9 Billy and the Regulators nabbed

Frank Baker and William Morton, the men accused of firing the shots that wounded and killed Tunstall. The Regulators claimed that the two men were

then shot and “killed while trying to escape.”

On April 1 Sheriff Brady and his men were ambushed

by the Regulators firing from behind an adobe wall in Lincoln. The Sheriff and Deputy George Hindman were

killed—the Sheriff was punctured by a dozen bullets—and Bonney was wounded

in the thigh.

Three days later on April 4 the Regulators led by

Brewster and Bonney were in Blazers Mill between Lincoln and Tularosa

looking for other members of the posse.

They encountered Andrew “Buckshot” Roberts a former buffalo

hunter and a rancher allied with the Doolan/Murphy faction. He had not been a member of the posse and

seeing how things were playing out was trying to sell his stock and

ranch and leave the Territory.

When the Regulators attempted to arrest him, he opened fire with a

Winchester rifle. In a quick, chaotic

gun fight Roberts was badly wounded in the stomach but managed to wound

four Regulators including Charlie Bowdre.

When he emptied his rifle, Bonney rushed him with the intention

of finishing him off, but the tough old hunter managed to knock

the Kid senseless with his empty weapon.

Buckshot retreated into a mill building where he found a single

shot Springfield 1865 Army rifle, a weapon of choice of old

buffalo hunters. Despite his grievous

wound from behind the thick walls of the adobe building Roberts was able to

pick off his attackers. When Dick

Brewer was shot through the eye and killed, the stunned Regulators broke off

the attack and fled. Roberts

died two days later of his wound.

|

| Dick Brewer, co-leader with Billy the Kid of the Regulators until he was killed by Shotgun Roberts. |

It was the first major setback to the

Regulators and with Brewer’s death Bonney became the clear leader of the

riders now loyal to McSween.

A county warrant was sworn out for Bonney and two others

for the murder of Sheriff Brady, but the Regulators now controlled Lincoln

where their numbers swelled to as many as sixty.

Newly appointed Sheriff George Peppin

enlisted members of two rustler gangs, including the Jesse Evans Gang and

began attacking Regulators he found outside of Lincoln. Regulators Frank

McNabb

and Ab Saunders were seriously

wounded during the gunfight at the Tunstall’s old Fritz Ranch. On July 14

Peppin felt confident enough to open a siege

of the Regulators who were hold up in several Lincoln buildings including McSween’s home. On the 16th Charles Crawford a posse sharpshooter assigned to pick off men

in a saloon, was killed by a better

sniper, Regulator Fernando Herrera.

A tense stand-off continued

for three more days.

On

July 19 Deputy Sheriff Jack Long and

posse member Buck Powell managed to

set McSween’s home on fire with the

lawyer, Bonney, and several others inside.

The defenders erupted with gunfire and they kept up until fire consumed

all but one room of the house. In the

scramble to escape the burning building McSween was shot and killed by Robert W. Beckwith, who was then shot

and killed by Bonney.

On

the run, Bonney and three other Regulators along with some Mexican freinds were

on the Mescalero Apache Agency on August 5 intent on steeling horses. While Bonney and the Regulators stopped to

water their own horses three of the Mexicans including former constable Atanacino Martinez

riding ahead were seen and attacked by tribal members who figured out

what they were up to. The gunfight

attracted the attention of agency bookkeeper

Morris Bernstein rode out and exchanged fire with Martinez who killed

him. Meanwhile Bonney and others at the watering hole came under attack and in the confusion he lost his horse. George

Coe hoisted the Kid behind him on his mount and the two of them rode around

the other gun fight and raided the Agency coral

making off with a fresh mount for Billy and most of the rest of the stock. The Regulators and Mexicans scattered.

Bonney

and the other three Regulators were indicted for Bernstein’s murder even though

Martinez turned himself in and made

a full, detailed confession alleging

that he shot only in self-defense. Authorities backed by the Dolan/Murphy

faction were not interested in a Mexican renegade—they

were out for the Regulators and particularly Bonney and knew that the murder of

an Agency employee would mean the Federal

Marshall and Army troopers would be on their case.

The

boys high tailed it to Fort Sumner, the abandon Cavalry post

that was now a Mexican village, which became their refuge for the next

months. Relatively safe from the

Sherriff’s posse pursuing them, they drank and gambled in the local cantinas and romanced the señoritas. It was a welcome

respite and it was during this time that the only absolutely authenticated

tintypes of Billy the Kid were taken. But during this time the Regulators began to

break up. The Coe cousins and Fred Waite left the group. More marginal members melted away.

After

a brief foray back to Lincoln to test the waters Bonney and his

remaining compadres rustled horses of the Fitz ranch and drove them to the Texas Panhandle town of Tascosa

where he sold them for good hard money which financed another period of wild

nights. Despite being known to be wanted

in New Mexico, he was apparently welcome

in Texas. The Kid even took time to compete in local shooting matches and horse races.

Meanwhile

U.S. Marshal John Sherman was frustrated in his search for the Regulators. On October 5 he reported to newly appointed Territorial Governor Lew Wallace that he had warrants for several

men involved in the Lincoln County War including “William H. Antrim, alias Kid,

alias Bonny” but was unable to execute them “owing to the disturbed condition

of affairs in that county, resulting from the acts of a desperate class of men,”

|

| A few years after his term as New Mexico governor, General Lew Wallace made the cover of Harper's Weekly when his novel Ben Hur became a sensation. |

Wallace

was a lawyer and a distinguished Civil

War Major General now best remembered as the author of Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ which

he completed during his occupancy of

the Governor’s Palace in Santa Fe. After considering

Sherman’s report Wallace declared a general

amnesty to participants on both sides of the Lincoln County War since the murder of John

Tunstall. But he excluded those, like Bonney, who had been convicted or indicted for

a violent crime.

The

offer precipitated the final break-up of the

Regulators with many returning to Lincoln County and others leaving the

territory. Although Bonney had been excluded, he had hopes that things had cooled down and that he might succeed in getting the pardon extended to

him. He dared return to Lincoln to see

what might develop.

He

had some reason to hope. Parties on both sides were tiring of watching their backs. On February

19, 1879 surviving members of both sides met in Lincoln, including Sheriff George Kimball, the latest in a

string of men to hold that precarious office,

met to parlay for peace. Jesse Evans, the former rustler gang

leader almost ended things before they began when he reached for his gun to

shoot Bonney on the spot but was restrained

by his friends. Both sides agreed to

stop shooting each other or friends or allies and to refuse to testify against each other at any trials. To seal the deal everyone went drinking together in a round-robin of local saloons—everyone but

Sheriff Kimball who slipped away to go to Ft. Stanton for troops to assist in

arresting the Kid.

It

will come as no surprise that bitter

enemies drinking together was bound to turn out poorly.

With everyone well in their

cups they encountered Alexander

McSween’s widdow’s lawyer Huston Chapman who was pursuing an indictment against the men

who killed her husband. James Dolan,

leader of the Dolan/Murphy faction and the principle

target of Chapman’s efforts, and a gaggle of his men accosted the lawyer and tried to taunt him into action. One

drew and fired at his feet. Bonney and his pal Tom

O’Folliard tried to get

away from the scene but were held by Jesse Evans at gunpoint and forced to

watch while Dolan and Bill Campbell

both shot Chapman and then lit his body on fire with kerosene where it lay in

the middle of the street.

In the confusion that followed Bonney and O’Folliard slipped away on

horseback before the Sheriff arrived to arrest him.

The

senseless brutality of the Chapman murder outraged Gov. Wallace. On

March 13 Bonney sent a note

to the Governor offering to testify

against Campbell’s killers in exchange

for having the indictments against him vacated

which would make him eligible

for the amnesty. Wallace replied, “I have authority to exempt you from prosecution if you will testify to what you say you know…If you could trust Jesse Evans, you can trust me.”

Two

days later Bonney slipped into the Governor’s office for a three hour

meeting. In exchange for his testimony

Wallace promised, “A pardon in your pocket for all of your misdeeds.” Two days later he and O’Folliard surrendered

to Sheriff Kimble as arranged.

Both

testified fully at several trials that followed. But both trial

judge Bristol and District Attorney William Rynerson were

members of the Dolan/Murphy political machine.

Predictably the trials either ended in acquittals or the accused were pardoned under the amnesty

proclamation. O’Folliard was granted his

pardon but Rynerson refused to honor Governor Wallace’s pledge to Bonnie. For his part the Kid expected the Governor to

intervene. But after days of delay it became apparent that Wallace would not act. Billy made yet another of his jail breaks and

disappeared into the desert.

Tomorrow—The

End of the Trail