Note—Until this year’s Coronavirus shortened season, the 1981 Major League

Baseball strike caused the longest disruption of games in history. .

On July 31, 1981 a strike against Major League Baseball (MLB) ended after the loss of 713 games—38% of the regular season. Negotiations between the owners and the Major League

Baseball Players Association (MLBA) were so bitter that MLB negotiator Ray Grebey and Players Association representative Marvin Miller refused to shake hands and pose with each other

for a customary bury the hatchet

photograph. Each would have rather

buried a hatchet in the other’s skull.

The relationship of Baseball to its employees had been bitter almost from

the very beginning of the National

League. Owners regarded players as virtual chattel bound indefinitely by iron-clad

personal service contracts that forbad players from seeking higher pay

at other teams. The result was an abnormally low pay scale which kept all

but a handful of stars in near poverty and gave the stars not much

more. Bitter players sporadically struck

individual teams without success, usually the so called ringleaders were banned for life from the sport.

As a result the Players’ League was formed in 1890 with most of the National League’s top stars. Although the league had a successful

season, it was under-funded and collapsed sending most of its

players back to the NL with their tails between their legs and worse off than

ever. Would-be rivals of the NL

like the American Association, American League, and Federal League took

advantage of player discontent to lure stars to their start-up challengers. Only the AL

A fall out of the Federal League collapse left the players in worse shape

than ever. The owners of the former

Federal League franchise in Baltimore Sherman

While the case was winding its way slowly through the courts, members of

the stellar Chicago White Sox team

chaffing under the notoriously tightfisted

rule of Charles Comiskey

demonstrated how damaging to baseball could be the players’ resentment. The team, or at least key members of it, accepted a bribe

from gambler Arnold Rothstein to throw

the 1919 World Series against the Cincinnati

To resurrect the tattered reputation of the game,

the owners appointed Federal Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis as the Tsar-like

Commissioner of Baseball. From the

owners point of view Landis was the perfect candidate. He had won national acclaim for heavily

fining Standard Oil of Indiana for attempting to fix freight

rates, and was a rabid opponent of unionism, Socialism and radicalism

in any form. He had presided over World

War I and Red Scare era trials of dissidents handing

out draconian sentences and frequently stretching the law to do

it. He presided over the trial of

101 members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) leadership

for sedition, sending all to prison for long terms. He was also a devoted baseball fan who had

maneuvered to avoid an earlier attempt to challenge organized baseball on

anti-trust ground in a 1914 suit brought by the Federal League. Most significantly he was the presiding

judge at Federal trial of the disgraced White Sox players.

Although Landis theoretically represented the

interests of all baseball, including players and fans, in fact at least

on issues surrounding player salaries, working conditions, and ability offer

their services freely to any team, he was steadfastly the owners’ man. He ruled the game until his death in 1944

blocking all reform.

It wasn’t until Landis was dead and Ford Frick

was Commissioner that players tried to form their first organization since

Landis crushed the National Baseball Players Association back in

1922. In 1952 the MLBPA was formed with

highly respected Cleveland Indian pitcher Bob Feller as its

first—and as it turned out—only President.

Under Feller the MLBPA attempted to function as a

professional association advocating for improved conditions attempting

to set up programs for retired and destitute members. However the owners flatly refused to deal

with them or modify any of the terms of employment that bound players to the

whim of the teams that literally owned them.

In 1959 the organization decided it was time to

get more aggressive. It

eliminated the executive presidency and brought in a professional Executive

Director to lead it. They really

took the plunge to becoming a real labor union seven years later in 1966

when Marvin Miller, a former United Steelworkers economist, lead

negotiator, and business agent was brought on board.

Miller meant business and set about to make the

MPBLA one of the strongest unions in America.

Broadcaster Red Barber would later categorize him with Babe

Ruth and Jackie Robinson as one of the most important figures in modern

era baseball. Certainly he shook

things up.

In just two years Miller obtained the first collective

bargaining agreement with the owners which raised the minimum pay—usually

for rookies and journeymen utility players—for the first time in

twenty years from $6,000 per season to $10,000.

That won the players’ undying loyalty and built unshakeable

solidarity.

Next, in 1970 Miller won arbitration. Previously when a player and his owner failed

to reach agreement on terms for a new contract, the dispute would be referred

to the Commissioner, the owner’s creature, who naturally tended to always side

with them. Arbitration took it to an independent

arbiter who picked between the two sides final offers. Increasingly the arbitrators found for

underpaid veteran players. And the

owners seeing that they had a lot to lose in the winner-takes-all system

became more flexible in their negotiations. Salaries for veteran players started to rise.

Arbitration paid off in a big way in 1974 when Oakland

A’s owner Charles Finley refused to honor a contractual agreement

to pay a $50,000 insurance premium for his star pitcher Catfish

Hunter. The arbiter ruled

that Finley had thus voided the contract and allowed Hunter to become a free

agent. The pitcher then was able to

sign with the New York Yankees for a then astonishing 5-year, $3.5

million contract. That whetted the

appetite of plays for effective free agency.

|

| Curt Flood and Players Association Executive Director Marvin Miller. |

Curt Flood had famously sued MLB

with the support of the players union claiming that the reserve clause which

kept the “owning team” in control of a player for a solid year after his

contract was up, meaning that the player could be kept from playing with any

team without the original team’s consent, was an anti-trust violation. The Supreme Court ultimately upheld the

admittedly shaky ground of the anti-trust provision.

After the victory with Hunter, Miller encouraged

two other players, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally to play out the

succeeding year without signing a contract. Then both players filed grievance

arbitration. The players won the arbitration with a ruling that both had

played out their obligations to their teams and were free agents. The notorious reserve clause was dead

and the era of free agency was ushered in.

With victory after victory under his belt, Miller

was cordially hated by the owners, but they seemed powerless

against the union. These years were

punctuated with short work stoppages—strikes in 1972 which lasted 13

days and in 1980 plus two spring

training two lockouts, in 1973 and 1976.

So the table was set for an epic confrontation in

1981. The owners sought protections from

the effects of free agency. In

particular they sought compensation for losing a free agent player to

another team—a player selected from the signing team’s roster not including

12 protected players. The union held that any form of compensation would

undermine the value of free agency.

With negotiations at an impasse the union Executive

Board set a May 31 strike deadline.

This was extended while a union complaint of unfair labor practices was

heard by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Finally, on June 15 the players walked

out.

Owners were stunned when most of the sporting

press and fans seemed to take the side of the players. They could not believe that they were not

viewed as beloved community leaders instead of as flinty hearted

capitalists. A Sport Illustrated cover screamed

“Strike! The Walkout the Owners Provoked.”

|

| These two New York Post stories reflected the heavy economic impact of the strike and the disappointment of fans. |

But as the strike wore on, fans became restless. And cities took a big economic hit. An estimated $146 million was lost in player

salaries, ticket sales, broadcast revenues, and concession

revenues. The players lost $4 million a week in salaries while the owners

suffered a total loss of $72 million.

Faced with the possible loss of the entire season

a compromise, which most considered favorable to the players, was

finally reached. Teams that lost a premium

free agent could be compensated by drawing from a pool of players left

unprotected from all of the clubs rather than just the signing club and players

agree to restricting free agency to players with six or more years of major

league service. Miller had never really

wanted unlimited free agency anyway fearing that a glut of players

on the market would drive compensation down.

|

| Pirate picher Luis Tiant reads about the end of the strike. |

Play resumed with the delayed All Star Game in

Cleveland on August 8. Because the game

was moved from its traditional mid-week slot to a Sunday, a record attendance

of 72,086 led owners to hope that fans would return to the game. They were wrong. Bitter fans stayed away in droves through the

rest of the season and TV and radio audiences shrank. Newspaper letter columns were filled

with fans declaring that they were done with the game. It took some years for the game to recover

from fan disillusion.

Some of that disillusion was stoked by the

slapped together play-off system used to determine teams for the World

Series. The leaders of the first

half of the season would face the leaders of the second half of the season in a

playoff. In case the same team won both

halves, it would face the team with the second best record. But the system produced anomalies. The Cincinnati Reds of the National

League West and St. Louis Cardinals of the National League East

each failed to make the playoffs despite having the two best full-season

records in the National League that season.

On the other hand, the Kansas City Royals made the postseason

despite owning the fourth-best full-season record in their division and

posting a losing record overall.

Miller retired in 1982 but the union he

built remained strong.

The MLBPA continued to frustrate the owners,

particularly when they successfully proved in court that the owners and

Commissioner were in collusion in attempting to circumvent the

free movement of players under free agency.

The collusion may also have affected the outcome of both the regular

season series and World Series of 1985, ’86, and ’87. Owners were fined a staggering $64.5

million and had to compensate player for losses related to multi-year contracts

and lost bonuses which eventually cost them another $280 million.

There was a one day strike in August of ’85 and

owners locked out player for early spring training in 1990.

In 1994 players struck on August 12 wiping out

the rest of the season and the World Series.

The strike only ended the next spring when a U.S. District judge issued

an injunction restoring terms and conditions of the expired agreement. That

traumatic event did even more damage to baseball.

Eventually fans came back and baseball also

bounced back from the steroid scandal that damaged the reputations of

stars like Mark McGuire, Sammy Sosa, and Roger Clemens.

Since then contracts have been renewed without

strikes or lockouts, despite some bluster. The union remains strong. Baseball remains the only sport without an

effective salary cap. Player

incomes and team profits are at an all-time high. Meanwhile the other major American sports—Football,

Basketball, and Hockey have all had substantial labor turmoil—largely

due to weak unions.

|

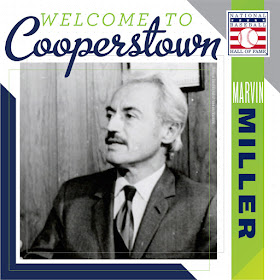

| The Baseball Hall of Fame's Twitter announcement of the election of Marvin Miller in December 2019 on his eighth appearance on the ballot. |

And what of Marvin Miller? He died on November 27, 2012 in New York

City at the age of 95. Owners successfully

fought repeated efforts to put him in the Baseball Hall of Fame

despite his undisputed impact on the game until a re-organized Modern

Baseball Era Committee finally elected him in December 2019, his eighth

appearance on the ballot. He was

slated to be inducted with the Class

of 2020 this summer but the ceremony has been indefinitely

postponed due the Coronavirus.