The Memorial Day Massacre--American Tragedy, 1937, by Philip Evergood was based on a press photograph.

Eighty seven years ago today it was hot and muggy in Chicago. But the Sun was shining brilliantly. Due to a week old strike and the Memorial Day holiday,

the giant steel mills nearby were not

belching their customary heavy smoke. Maybe those unaccustomed dazzling

skies contributed to the air of a holiday outing as steel workers, their wives in their finest summer dresses,

and their children converged by bus,

trolley, auto, and foot on Sam’s Place, an erstwhile dime-a-dance hall, turned into a makeshift soup

kitchen and strike headquarters on

the Southeast Side less than a mile

from the Republic Steel mill.

It was May 30, 1937. The

Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC),

the pet project of John L.

Lewis’s Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), had shocked the nation earlier in the year by bringing industry behemoth U.S. Steel under contract by infiltrating the company

unions and having them vote to affiliate. Faced with rising demand from an apparent recovery under way from the depths of

the Depression on one hand and a popular,

labor friendly administration

in Washington on the other, the

nation’s dominant steel company quietly surrendered.

Buoyed by the success, organizers

turned their attention to Little Steel,

the smaller, independent operators

in Pittsburgh, Youngstown,

Chicago and other grimy industrial

cities. But the bosses of Youngstown Sheet and Steel,

Republic, Bethlehem, Jones and Laughlin and

others were a tougher bunch than the Wall

Street stock manipulators that

ran the huge rump of the old Steel

Trust. In fact they had nothing but contempt for the

monopolists, their old business enemies, and their “weakling”

attitude toward unionization. Little

Steel vowed to fight.

Tom Girdler, President of

Republic, had said that he would go back to hoeing potatoes before he met the strikers’ demands.

The ferocity of the opposition to

unionization was not just empty rhetoric

either. They had shown they meant

business in blood on more than one occasion.

Famously in Youngstown,

Ohio back in 1916 strikers

accompanied by their wives and children marched from the slums to the gates

of the Sheet and Tube mill to keep strike breakers from reporting to

work. Inside the gates a small army of private security forces responded by throwing

dozens of tear gas bombs. As the thick, poisonous haze hung over

the workers obscuring their vision, guards unleashed volley after volley of rifle fire directly into their ranks.

The exact toll may never be known as workers were afraid to bring the

wounded to medical attention. At least three were killed, probably twice that many including women. Twenty-seven injuries were confirmed,

but strikers made oral reports of

more than a hundred. Enraged as the dead

and wounded lay bleeding on the ground the strikers attacked the guards with stones

and bricks and perhaps a pistol shot or two before retreating

to town.

In rioting over the next two days, workers burned much of the town’s

business district only to be eventually crushed by Ohio National Guard troops.

The memory of those events

was still fresh to workers more than twenty years later. Especially when Little Steel bosses quietly let

it be known that they had been stockpiling

armories for years and were ready, even eager to repeat the carnage.

The USWOC called their national

strike against Little Steel a week earlier.

In Chicago it had been marred by predictable violence,

particularly on the part of the Chicago

Police Department which had a long history of being used as armed strike breakers. Beatings and arrests on the

picket lines were occurring daily. Some

strike leaders had been kidnapped

and held incommunicado. For their part senior police officers were “subsidized” by corporate bosses who

also bought political clout with the

usual campaign contributions and bribes to local officials. They also pledged to reimburse the city for police overtime

during the strike. In addition the

still largely Irish Catholic force

was kept inflamed by homilies preached

in their parishes deriding USWOC as

“Godless Communists.”

Despite this, morale among the strikers was high.

After only a week out, families had not yet felt the full pinch

of lost incomes and strike soup

kitchens kept them fed.

Organizers made a point of engaging workers’ wives from the beginning,

including them in planning and giving them important support roles.

This was critical because many a strike had been lost in the past

when families went hungry, and the women urged their men to return to work.

As the large crowd gathered at Sam’s

Place for the first mass meeting of the strike, vendors plied the crowd with ice

cream, lemonade, and soft drinks. Meals were passed out from the soup

kitchen. Other families munched on sandwiches wrapped in wax paper

brought from home. Many of the men

passed friendly bottles as they settled into a round singing—mostly old Wobbly songs including Solidarity Forever and Alfred Hayes’s I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night.

Then came the rousing speeches. Joe Webber, USWOC’s main organizer pointed his finger at

the distant plant. The plan was to establish the first mass picket at the gates

of the Republic Works. Some workers

carried homemade signs. Organizers passed out hundreds of pre-printed placards stapled to lathing emblazoned with slogans.

With a sense of a gay holiday

parade the strikers marched away from Sam’s Place behind two American flags singing as they went one

block up the black top and then turned into the wide, flat prairie that separated them from the

distant plant.

Many of the surviving press photos--the police confiscated and destroyed

as much film as they could lay their hands on--was damaged. Still,

they tell an unmistakable story. Police continue to beat the helpless

in the pile while launching more tear gas as firing at those still

fleeing.

Historian/novelist

Howard Fast later described the scene.

…snake-like, the line of pickets

crossed the meadowland, singing at first...but then the song died as the

sun-drenched plain turned ominous, as five hundred blue-coated policemen took

up stations between the strikers and the plant. The strikers’ march slowed—but

they came on. The police ranks closed and tightened… now it was to unarmed men

and women and children that a police captain said, “You dirty sons of bitches,

this is as far as you go!”

About two hundred and fifty yards

from the plant, the police closed in on the strikers. Billies and clubs were out already, prodding,

striking, nightsticks edging into women’s breasts and groins. It was great fun

for the cops who were also somewhat afraid, and they began to jerk guns out of

holsters.

“Stand fast! Stand fast!” the line

leaders cried. “We got our right! We got our legal rights to picket!”

The cops said, “You got no rights.

You Red bastards, you got no rights.”

Even if a modern man’s a

steelworker, with muscles as close to iron bands as human flesh gets, a pistol

equalizes him with a weakling—and more than equalizes. Grenades began to sail

now; tear gas settled like an ugly cloud. Children suddenly cried with panic,

and the whole picket line gave back, men stumbling, cursing, gasping for

breath. Here and there, a cop tore out his pistol and began to fire; it was

pop, pop, pop at first, like toy favors at some horrible party, and then, as

the strikers broke under the gunfire and began to run, the contagion of killing

ran like fire through the police.

They began to shoot in volleys. It

was wonderful sport, because these pickets were unarmed men and women and

children; they could not strike back or fight back. The cops squealed with

excitement. They ran after fleeing men and women, pressed revolvers to their

backs, shot them down and then continued to shoot as the victims lay on their

faces, retching blood. When a woman tripped and fell, four cops gathered above

her, smashing in her flesh and bones and face. Oh, it was great sport,

wonderful sport for gentle, pot-bellied police, who mostly had to confine their

pleasures to beating up prostitutes and street peddlers—at a time when Chicago

was world-infamous as a center of gangsterism, assorted crime and murder.

And so it went, on and on, until

ten were dead or dying and over a hundred wounded. And the field a bloodstained

field of battle. World War veterans there said that never in France had they

seen anything as brutal as this.

Because workers were afraid to bring

their injured to hospital, the exact casualty count may never be known

for sure. Ten men were confirmed dead.

All shot in the back. More than 50 gunshot

wounds were reported. At least a hundred were badly injured, many more with

scrapes, bruises, and turned ankles from police clubs

and the panicked stampede to escape.

Many reporters and photographers

were on the scene. Police confiscated most of their film. Newsreel

cameras caught the action, but the companies were pressured not to show the footage.

The next day, led by the rabidly

anti-union Chicago Tribune, most of the press dutifully recorded that the

police had come under attack by fanatic Reds and had acted in

self-defense.

The rabidly anti-union Tribune spread the lie that Communist radicals had attacked police. They threatened their own reporters who knew better.

Although covered in the labor press, the nation as a whole was

kept in the dark about what had happened.

Even the workers supposed friend Franklin D. Roosevelt,

pretty much accepted the official account and told reporters that “the

majority of people are saying just one thing, ‘A plague on both your houses.’”

A Cook County Coroner’s Jury ruled the deaths that day as justifiable homicide. Not only was no action taken against any of

the police involved that day, but senior officers were commended and promoted.

The truth about what happened was

very nearly suppressed, as so many atrocities committed against working

people had been. But a single newsreel

cameraman saved the footage he shot

from the roof of his car. Some of the

photographers on the scene retained their shots. The stills and the moving pictures were placed on exhibit during the hearing on Republic Steel Strike held by a subcommittee of the Senate Committee on Education and Labor almost a year later. A shocked nation saw for itself the

senseless, unprovoked brutality of

the police.

The Ladies Day massacre outside of the Youngstown

Sheet and Tube plant later in July showed that Little Steel Bosses were

still committed to smashing the strike with brutal force.

As for the strike, it dragged on

through the summer, as did regular violence on picket lines. Then on July 19th it was Ladies Day on the picket line in front of the Republic Steel mill

in Youngstown. After company guards

assaulted one of the women, they were pelted with rocks and bottles. Retreating into the plant, in an eerie replay

of the 1916 violence, guards let loose with tear gas and then opened fire, many

firing down on the crowd from virtual

snipers’ nests. At least two were

killed and dozens wounded. Once again

the National Guard was called in and the town became a virtual occupied territory. The strike was crushed, and workers went

back.

But the Steel Workers turned to the

new National Labor Relations Board

for help. They complained of unfair labor practices by the Little

Steel companies. The case took years to

resolve. But in 1942, with another war

on and the need for industrial peace,

the NLRB ordered the companies

to recognize what had become the United

Steel Workers Union.

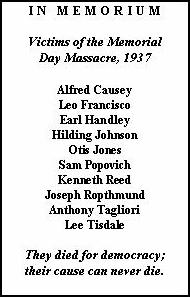

The Memorial Day Massacre victims remembered.

Today a local union hall stands on the site of Sam’s Place. The Republic Mill and other Little Steel

plants are closed and pad-locked eyesores or have been torn

down for largely undeveloped parkland.

The City seeks desperately to find some way to redevelop what are now called

simply Brown Fields. At one time the site was suggested as one

possible future home for Barack Obama’s

Presidential Library, but it was passed over. USW members and the Illinois Labor History Society sometimes gather in remembrance of

that terrible day. And the last aging

survivors, including some of the children present, fade away one by one, their

stories untold.

This year again there will be scant

mention of the Memorial Day Massacre or coverage of commemorations. Seems like Chicago is still eager to forget.