Note—This post required extensive

research to refresh my once solid knowledge of this history. Time erodes things.

Last Sunday, May 25, was the 200th anniversary

of the founding of the American Unitarian Association in Boston by ministers

serving mostly in and around the Hub of the Universe in 1825. The ministers all served self-governing congregations

that were affiliated with the New England Standing Order, the former

state church of Massachusetts, Maine, Connecticut,

and New Hampshire.

The Rev. Sofía Betancourt, President

of the Unitarian Universalist

Association (UUA) wrote:

…we celebrate 200 years of

the American Unitarian Association at a time when Unitarian Universalism is

badly needed in our nation and in the world. We should be proud of the

accomplishments and impact of liberal thought and the theology that grows from

that thought. Yet too there is trouble born of comfort in thinking that we know

best when it comes to restoring justice and building a world and an Earth

community that allows all to fully thrive.

So how do we proceed as

authoritarianism is on the rise both domestically and around the world? We must

remember that we are a sanctuary people—not only in collaborating around the

work of justice, but also in providing nourishment and shelter for our own

spirits so that we do not give up in the face of all that is.

Happy anniversary, beloveds.

May this milestone year be one that galvanizes us in all the ways we are called

to live into this moment and organize around our shared values in community.

Liberal preachers had been drifting away from the

rigid orthodoxy of hell-fire-and-damnation Calvinism that arose

from Puritanism since before the American Revolution. Inspired by the Enlightenment these

ministers were increasingly skeptical of the Doctrine of Predestination,

the literal as opposed to symbolic or poetic absolute truth of every Bible

story, proof by miracles, and finally even the divinity of the

man named Jesus and the Doctrine of the Trinity.

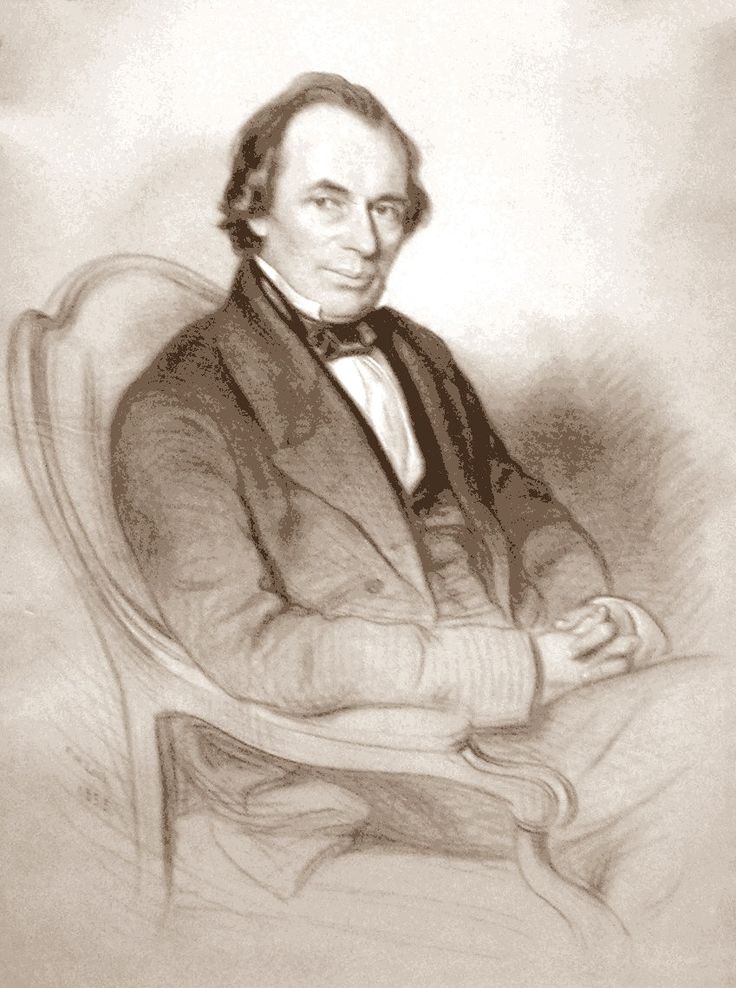

Rev. William Ellery Channing defined Unitarianism in his Baltimore ordination sermon in 1819 and was a prime mover in establishing the American Unitarian Association.

These differences became more

profound after The Rev. William Ellery Channing preached an ordination

sermon for Rev. Jarred Sparks at the First Independent

Church of Baltimore on May 5, 1819.

The speech published in pamphlet form as Unitarian Christianity

outlined a broad platform of belief and gave the movement an identity and a name—unitarianism. Unitarianism was once an epithet used against

non-Christian monotheists including

despised Jews and Muslims and a handful of heretic

anti-Trinitarians. Channing threw it

in the face of the descendants of Cotton Mather—Sinners in the Hands of

an Angry God—who dominated the Standing Order. Asserting unitarianism was not even the main

focus of the address. The right to read

and interpret scripture using individual consciousness and reason

was.

An open breach of the old Standing

Order became inevitable. The

traditionalists became the Congregational Church and dominated outside

the environs of Boston and port cities.

The fiercely independent liberals resisted any form of ecclesiastical,

Presbytery, or other denominational structure. They adhered to the Cambridge Platform of

totally independent and self-governing congregations. Aside from voluntary reciprocal cooperation

of neighboring congregations and informal cooperation among ministers the newly

define Unitarians lacked any cohesion.

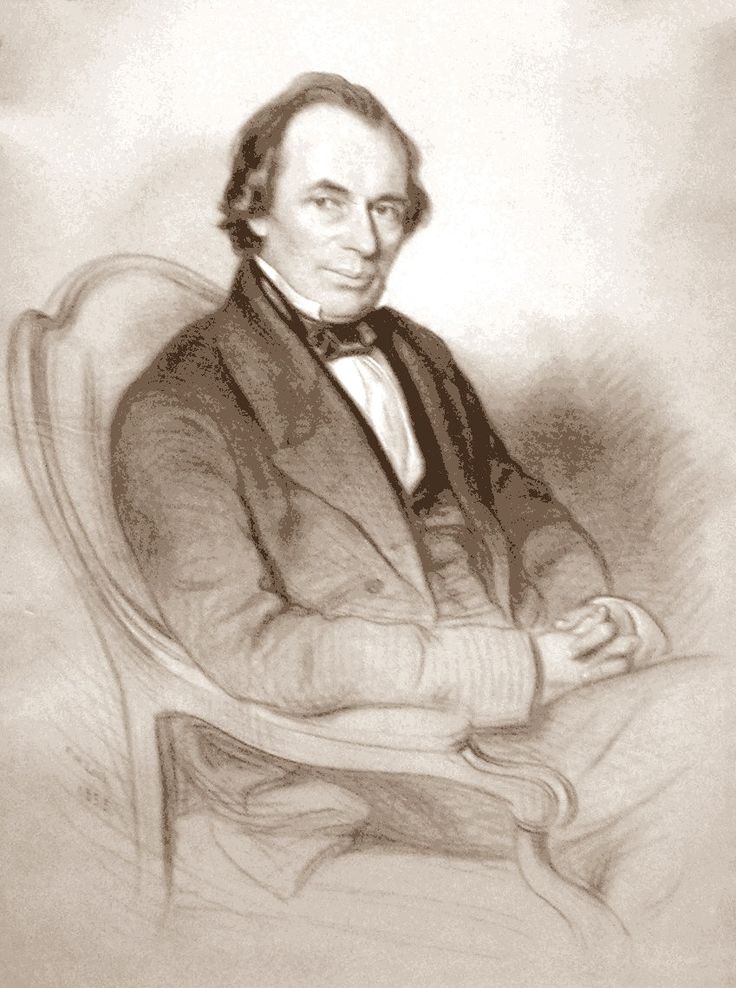

Andrews Norton, influential Harvard scholars was among the insurrectionists who founded the AUA but within a few years the so-called Unitarian Pope--was the leading voice for suppressing dissent from a new orthodozy.

The need to compete with the

Congregationalists, Episcopalians, Quakers, Universalists and

other denominations with well-established national and regional press and

resources for publishing tracts, pamphlets, and sermons. After private conversations and letter

exchanges William Ellery Channing; Andrews Norton, Harvard Professor

of Sacred Literature known to

friends and enemies alike as “the Unitarian Pope;” and Henry

Ware, the senior along with wealthy and influential laymen like convened

a semi-chaotic meeting in January 1825.

The meeting call stated they were to consider “the practicality and

expediency of forming a Unitarian convention or association, to consist of

clergymen and laymen, to meet annually or oftener.”

After a day of wrangling the meeting

adjourned with the intent of forming a committee or commission to study and

make recommendations. Like many such committees

it never really got together. According

to an account in short play by Nancy McDonald Ladd in UUWorld:

….on May 25, 1825, an energetic group of younger

ministers led by James Walker, Henry Ware Jr., and Ezra Stiles

Gannet, all of whom had been present for that historic debate, went rogue.

They arrived at the Berry Street Conference in Boston and personally

presented their own plan for a new convention of Unitarian clergy. Met with

affirmation from certain members of that body, on the very next day—May 26,

1825—they chartered the American Unitarian Association.

Henry Ware, Jr. was among the young ministers who got the AUA going.

By an amazing

coincidence the very same day that the British and Foreign Unitarian

Association was chartered across the puddle establishing an official body

for radical dissenting congregations in Britain and Ireland after

restrictions on their worship were lifted by Parliament. The kissing cousins were somewhat different

in theology and Christology and significantly different in governance. The Brits adopted a Presbyterian structure.

The new AUA was not

an organizations of churches or parishes.

It was strictly a voluntary association of Ministers individual laymen

with an interest in fostering the spread of Unitarianism. It was governed by a Board and

employed a part time secretary essentially someone to take notes, open

the mail, and assist the elected Treasurer in the banking details of

collecting and spending money. He was

also tasked with maintaining an annual roster of Ministers who were understood

to be Unitarian in theology and preaching.

Within a few years the annual list became considered a more or less

official recognition.

Trouble began because

it was subject to the whims, prejudices, and the reliability of information

available to a clerk. Some who wished

to be included were turned down with no explanation, but usually because of

some variation from an unexplained “norm” or because of scandal and perceived moral

defects. Andrews Norton became the

champion of a Unitarian Orthodoxy while many younger ministers were drawn into

the orbit of Transcendentalism or were influenced by Free Thinking. Applications were turned down from the suspected “heretics”

and even from those who were suspected of any association with them.

Conversely, some enrolled

ministers demanded to be removed mostly in protest to Nortons heavy hand.

Although ostracized by Unitarian traditionalist because of his outspoken abolitionism and militant support of Fugitive slaves, Rev. Theodore Parker became the inspiration for the first new minister members of the post-Civil War AUA.

There were many

subsequent challenges that the barely organized AUA struggled with—divisions over

slavery and the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act, how close

to adopt radical abolitionism or distance itself from it, and especially

the inability to plant new congregations outside of New England and to recruit

and support missionary ministers.

Unitarians seemed doomed to be just a local tribal sect rather than a

vital part of the American religious rights.

Brilliant radicals like the Rev. Theodore Parker showed a

new way but were ostracized by the previous generation of rebels.

The Civil War and

its aftermath demanded a new organization of congregations rather than

individuals with denomination like authority—the National Conference of

Unitarian and Other Christian Churches.

A special meeting of the AUA was

held on December 7, 1864 which, recognized the

need of enlarged denominational

activity with a resolution calling for “a convention, to consist of the pastor

and two delegates from each church or parish in the Unitarian denomination, to

meet in the city of New York, to consider the interests of our cause, and to

institute measures for its good.”

Rev.

Henry Bellows, prime mover and first Chair of the Board of the General Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian Churches.

The Convention was

held in New York on April 5 and 6, 1865

and organized the National Conference of Unitarian and Other Christian

Churches. The name was changed to General Conference of Unitarian and Other

Christian Churches at Washington, D.C. 1911. There was resistance by Cambridge Platform purist

congregations and ministers who did not, at least immediately, join the new

Conference. The prime mover was the Rev.

Henry Bellows, a practical second generation Transcendentalist with

immense organizations skills honed as the leader of the United States

Sanitary Commission which supported sick and wounded Federal troops

during the Civil War. From 1865 to 1880

was chairman of its council.

The General Conference

did not replace the AUA, which continued to be active as an individual

membership organization and a continuing support for Unitarian outreach. The National Conference, and after about 1875

the semi-independent Chicago based Western Unitarian Conference provided

direct support for member congregations and their ministers. The WCA under the leadership of the Rev.

Jenkin Lloyd Jones was the more social justice and labor friendly as

well as embracing humanism, Free thought, and inspiration by non-Christian

world religious traditions. The General

Conference wanted to keep Unitarianism in the Christian orbit for respectability

among the “better classes” of people.

Felix Adler, the ethnic German Jew who was founder of the Ethical Humanist Movement, a close ally of Jenkin Lloyd Jone's Unity Movement, and a prominent figure in the Free Religious Association.

Many of those

rejected who rejected explicit Christian identity formed the alternative Free

Religious Association in the 1870’s which flourished for a few years

before gradually being reabsorbed by an evolved AUA and General Conference

Former President and

Chief Justice served as President of the Conference during World War

I and the Red Scare after. He

also purged pacifist ministers and those with connections to radicals in

the Socialist Party and Industrial Workers of the World.

The post-Great War

period matched accelerating technical and industrial innovation and pervasive

shock and disillusion over the carnage. The

AUA and Conference were riven over demands by traditionalists for explicit

identification as Christian and demands for or limits on freedom of

conscience protections. Compromises,

unacceptable to the most passionate on each side, were made.

Humanism became the dominant tendency of Unitarian and later Unitarian Universalism in the second half of the 20th Century.

Unitarian ministers,

and some Universalists who were going through similar struggles, were prominent

signatories to the first Humanist Manifesto in 1933. The Manifesto gained more support during the Great

Depression and another looming World War.

In 1941 the American Humanist Association was formed. Many ministers and prominent lay people

retained affiliation. Their influence

grew and by the mid-1950s Humanism was the dominant strain of Unitarianism. They continued dominance into the early 21st

Century.

Along the way the

divided rolls and authority of the AUA became cumbersome and expensively

duplicative. In a major reform and reorganization

the AUA subsumed the Conference but adopted much of its structure and

governance including being an association of congregations. The AUA continued to honor and accept

individual members, but those members would not have much voting power at annual

May Meetings (conventions) compared to representatives of congregations

who cast important votes based on their membership numbers.

The post-war AUA

sought to broaden to include other progressive bodies into a new Council of

Liberal Religion. Outreach went out

to liberal Quakers, progressive Congregationalists, Ethical Humanists,

and others. The Congregationalists had

similar goal but instead formed the new United Church of Christ with

some Reform churches, and independent congregations. Relations between the cousin organizations

remained cordial and they collaborated especially on social justice issues.

The 19th Century seal of the Universalist General Convention.

While the Council

never really took off, relations with the Universalist General Convention (later the Universalist Church in America) did. Universalists had deep roots in New England

and a semi-mythological origin story.

Believers in universal salvation by a loving God and

radical egalitarianism in this life, they were organized by mostly self-taught

preachers and began forming regional conferences

after the Revolutionary War. The

Universalists in the early years tended to be farmers, local merchants and

trades people, some respectable if not wealthy gentry, and even laborers and

(in some cases) Black Freemen.

The class divide with Unitarians, especial the old Boston Brahman

elite, was intense. But over the next century and a half each

group evolved, theological divisions blurred, and shared a general liberal

religious outlook.

The interesting and

complex story of the Universalist is too long to consider here. Another day perhaps.

Prominent Unitarian Minister Rev. Dana McLean Greeley (center) at his inauguration as first President of the new Unitarian Universalist Association flanked by Rev. Harry B. Scholefield (left) and Lawrence G. Brooks. The dynamic leader committed the new Association and its resources to the Civil Rights movement and anti-war protest. He was often on the streets and front lines of the struggle and was arrested. He set a pattern of UUA leaders as outspoken social justice activists.

In the 1950s the two

faiths began sharing religious education materials, curriculum, and even a

youth group—Liberal Religious Youth (LRY). Then they began cooperating on publication. Serious talks about a possible

merger heated up culminating in the consolidation

(never say merger) into the Unitarian Universalist Association (UUA) on May 15, 1961. The Universalist had to adopt Unitarian congregational polity.

Regional conventions, stripped of any real authority, were allowed to

meet but slowly faded away. Unitarians

ended individual membership except for Life Members, the last of

whom passed in the early 21st century. A

statement of principles was largely adapted for Universalist practice and

eventually became the Seven

Principles which were the closest

to a statement of faith. After a lengthy

discussion those Principles were replaced by a set of guiding values centered

around Love.

The current Unitarian Universalist logo in Pride Month rainbow colors.

The UUA’s continued evolution as the most visible and influential liberal

religious voice in North America is also

another story on a long and winding path.