|

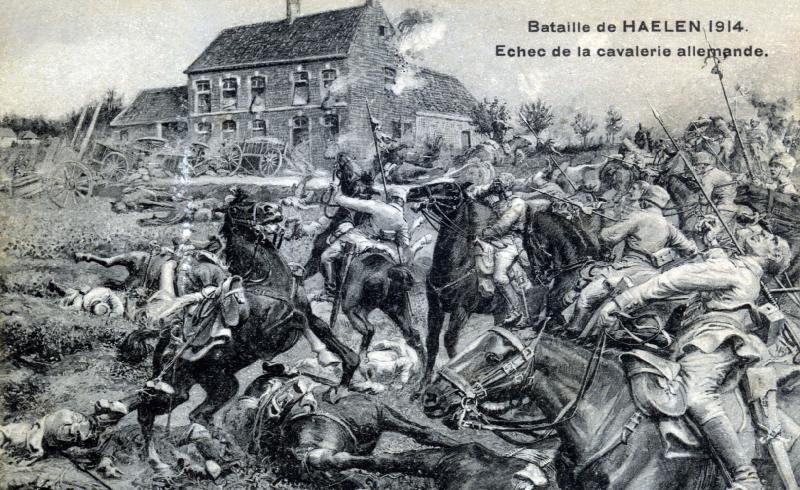

From a German postcard: "Battle of Haelen 1914, Defeat of the German Cavalry.

|

It

should have been a perfectly splendid affray

at the onset of what all sides seemed to think would be a glorious war providing for noble spectacle and opportunities for gallantry and honors sadly missing from Europe

for generations. The Great War was all shiny and new and

all of the powers leaping madly into

the melee were sure of rapid victory and Christmas at home. And what

could be a more fitting opening chapter than a clash between the dashing cavalry of two opposing armies, each still fitted out

in splendor as if for a victory parade down a broad avenue. It happened near a river ford town named Haelen in Belgium on August 12,

1914.

Thing had moved

briskly in Europe since the assassination of an Austrian Archduke in his

comic opera uniform and his wife in Sarajevo on June. July was wasted on a complicated series of

threats, ultimatums, and rejection that spread complex patterns to countries

far removed from the original clauses.

On July 28 Austria-Hungary finally

declared war on Serbia and three

days later Germany declared war on Russia for mobilizing to intervene on behalf of its ally and client state

Serbia. The three great Central and Eastern European empires were now committed, but the contagion could not be confined.

On August 2 Germany invaded Luxembourg, obviously intending to move on Russian ally France.

The next Belgian government refused a German ultimatum to open its

borders to the passage of German troops and Britain government guaranteed

military support to Belgium should Germany invade. Contemptuously ignoring the

warning Germany immediately entered Belgium and formally declared war on

France, the British government ordered general mobilization and Italy declared

neutrality. The British mobilized and

sent another ultimatum to Germany then quickly declared war on Germany at

midnight on August

4 Central European time. The

Belgium declaration of war was a final formality as the German army moved on Liège.

The

problem was that huge armies of the major powers, each calling millions of men

to arms, dwarfed anything before it in both complexity and the relatively short

periods of time available. The notoriously efficient Germans with their highly

trained, professional and largely Prussian

General Staff and senior officer

corps were able to get their large army on the move more quickly than

France, which was still scrambling, and Britain which had to mover an expeditionary force from the home

islands.

But

even the Germans, like everyone else, were rusty.

They had not been in major combat since the Franco-Prussian War in 1870.

Only a handful of the most decrepit

senior generals had even been lieutenants

in that conflict. The French, who were

mad to revenge their humiliating defeat in 1870, had fought rebellions in their North African possessions but had

mostly used their mercenary Foreign

Legion troops who by law could not serve on French soil. The British had been very busy with a

seemingly endless succession of colonial

wars in India, the Sudan, Afghanistan, and of course the Boer Wars in South Africa. They had many combat seasoned officers and highly professional regiments in

addition to reasonably trained reserves—and,

of course, unchallenged world naval

superiority. But naval superiority

would not immediately mean much in a land war in Europe and the British had not

engaged a modern European army since the Crimean

War which had ended way back in 1856.

And that had gone very badly for the British whose troops were poorly equipped,

clothed, and supported and who were pounded in a relentless and brutal trench warfare campaign which should

have been taken as lesson, but was, instead treated as an aberration.

These

armies had modern weapons—bolt action rifles that gave individual

soldier and units many times the firepower

of their Napoleonic Era counterparts,

machine guns whose death dealing

capabilities had not yet been fully understood as rendering old fashion mass maneuver and the gallant charge obsolete, light-weight

and mobile mortars that could move

and advance with infantry, and breach-loading and rifled cannon that could heave explosive

shells far beyond the range of smooth

bore cannon with greater accuracy. But they still moved by horse power. No European army yet had more than a relative

handful of trucks. Civilian automobiles were in use as staff cars and a few were being tried

out for scout vehicles, but since

they could not operate reliably off roads were of limited use. Motorcycles

competed with bicycles and horses as messengers where telephone lines were down or

unavailable. The Germans were using some limited radio communications as well, but the equipment was too bulky to

accompany units in the field. While in

the mobilization phase, internal railway

systems could deliver men and materiel to marshalling points, but

after that—and certainly after entering enemy territory—artillery, ammunition, and baggage was all horse-drawn

greatly limiting the speed with which any army could advance even under

ideal conditions with little or no armed opposition.

So,

despite light opposition by the Belgians who were scrambling to get their small

army in place and hopping for the early arrival of the French and English in

large numbers, the Germans were not exactly slicing through the small country at lightning speed. You are

thinking of the highly mechanized Panzer

Divisions that enabled the Blitzkrieg of the next war. The Germans were plodding to Liège slowly and behind the detailed plans of the General

Staff.

|

| German Cavalry on the move early in the war. These are Hussars--note the distinctive jackets worn draped over the left shoulder, the hallmark of this kind of cavalry. |

Which

is where the cavalry came in. All of the

European armies still carried large forces of cavalry, many still carrying lances for use against tightly packed

infantry formations. All of these forces

were now also armed with rifles, carbines,

and horse pistols. They were to be used as cavalry had been

deployed for centuries—for scouting and

reconnaissance, for screening the flanks infantry to prevent ambushes or surprise

attacks, for rapid movements ahead of the main army to seize strategic points like cross-roads

and river fords, to harass the enemy rear and disrupt baggage

trains, over-run artillery positions, and finally in pitched battle as shock troops to shatter enemy infantry

formations. In the course of such

operations it was to be expected that cavalry of opposing sides would discover

each other resulting in that most glorious of all actions, a mounted cavalry

battle with the blare of bugles, charges

and counter charges, sabers slashing.

Like

many units of most armies, the Cavalry was still outfitted in the splendor

befitting old Napoleonic glory, or an only moderately subdued version of

it. Even infantry was not immune—the French

Poilus

marched to war in bright blue coats,

red trousers, and kepis.

The Germans already preferred their gray uniforms, but many troops

still wore patent leather spike helmets. Only the British who had learned from bitter

experience in all of their colonial wars that their traditions scarlet coats only made their troops

easy targets, had adapted to dun brown woolens

and a variety of soft caps and hat to provide regiments with

distinctiveness. But the cavalry, the

glorious cavalry were still in their gleaming silver helmets, or some other elaborate headdress, knee-high polished boots with spurs, cut-away jackets with split tails or waist-length tunics, gauntlets, and scabbered sabers still cut

dashing figures. Uniforms, including the

colors of coats and breeches, might vary between types of

horsemen—Hussars (light cavalry), Dragoons (multi-purpose assault and reconnaissance, frequently used as mounted infantry to fight on foot), Lancers (assault against infantry and artillery), and Cuirassiers (heavy cavalry with rifles

or carbines and assault troops—and between regiments.

| Representative uniforms of Belgian cavalry units in World War I. Some of those at Haelen also wore silver helmets, but they never got to fight from the saddle. |

The

German generals decided to deploy their gaily bedecked cavalry—they had two

whole divisions organized as the II Cavalry Corps under General Georg von der

Marwitz. Cavalry scouts

sent ahead to reconnoiter along the routes to Antwerp, Brussels

and Charleroi reported on August 7 a

gap in the Allied line between Deist and

Hay.

On August 11 Belgian cavalry scouts reported a large movement

of troops, including infantry, cavalry, and artillery were rumbling on the

move. Anticipating an attempt to breach

the gap before more French reinforcements could arrive, the Belgian cavalry

division under Lieutenant-General Léon de Witte was dispatched

to secure the bridge over the River Gete

at Haelen and either block the German advance or delay it long enough for

the gap in the line to be filled. De

Witte was also pointedly ordered to use his cavalrymen as infantry and not to

challenge the Germans on horseback.

Those

are disappointing orders for any

cavalry commander, but de Witte complied speedily. His mounted forces could move quickly to Haelen

and had time to take up defensive

positions with excellent cover. His

force consisted of five mounted regiments with 2,400 men, bicycle company with 450 riflemen, and one company of pioneers (armed engineers). He

concentrated his forces at the rear of the village and spread some along canceled

positions on his flanks should he be overwhelmed.

Also

on the 11, the German 2nd Cavalry Division under Major-General von Krane was ordered ahead towards Spalbeek and the 4th

Cavalry Division under Lieutenant-General

von Garnier was to advance via Alken to Stevoort.

But neither force moved until August 12 because their horses and men

were exhausted from a forced march in intense summer heat and sufficient oats for the horses had not caught up

to them.

Before they could move, however, the Belgians intercepted an encoded

radio message that revealed the German force and its destinations—one of the

first such instances in modern war and a red-flag

warning to secure messages

floating in the airways for anyone to pick up.

Belgian headquarters quickly dispatched the 4th Infantry Brigade to reinforce de Witte at Haelen

Germans from the 4th Division attempted to cross the Gete

behind a screen provided by members of two Jäger battalions (literally hunters but elite specialized ranger units used as advanced skirmishers often in conjunction with

the cavalry.) The movement was detected

and 200 advanced Belgian skirmishers set up defensive positions in the building

of the town inflicting a whiting fire on the attackers. Belgian pioneer blew the bridge but it failed to completely collapse. German artillery rousted the defenders from

the village sending them back across the river.

Von Krane managed to get about 1000 of

his mounted troopers across the bridge and into the town. He must have been confident that he could scatter an inferior enemy. He was

wrong. There was soon hell to pay.

The main Belgian line stretched west from the

town and was hidden behind copses, hedges,

and farm building. Attacks there were repulsed because the

attackers could not, in most cases even see the defenders or make out how they

had deployed their line making traps likely.

Haelen and to the south the Jägers and the 17th and 3rd Brigades of

the 4th Division tried to advance through some corn fields. Here they met

disaster despite support from artillery and from a machine gun company. The

dismounted Belgians poured vicious fire into repeated charges by the cavalry,

cutting the advance units to pieces as men and horses got tangled in barbed wire farm fences and floundered

in a sunken road where they were

picked off by sharpshooters and raked with machine gun fire.

|

| The grim aftermath of the battle. |

At the end of a long

afternoon of sharp fighting the German retreated, the battered 4th Division

toward Alken and the 2nd Division

toward Hasselt. It was a stunning victory for the plucky and

outnumbered Belgians and a devastating loss in pride and prestige for the

German cavalry. Both side sustained

heavy casualties—the Belgians lost 160 dead and 320 wounded and the Germans

lost 150 dead, 600 wounded, 200–300 prisoners. But 4th Division alone lost a combined 501

men dead and wounded and 848 horses—casualty rates of 16% for men and 28% for

horses. That far exceeds the classical definition

of decimation. Far from expected glory, the German

cavalry was given a grim preview of the relentless war ahead.

Despite the valiant stand, which is still celebrated by the

Belgians if forgotten by everyone else, the action at Haelen barely slowed up

the German advance across the country. Germans

besieged and captured fortified Namur, Liège, and Antwerp and were not stopped until the Allies could mass enough

troops along the Yser in late

October of 1914 leaving the Germans in control of most of Belgium. Then the war began to settle down into the

grinding years of trench warfare so etched in the popular memory.

|

| All that's left of glory--a gleaming helmet of a member of the German 2nd Cuirassiers found on the field of battle. |

At home German propagandists turned the defeat of the Cavalry

at Haelen as a gallant but futile loss, much as the English had romanticized the doomed Charge of the Light Brigade in the

Crimea and the Americans had lionized Custer

and the 7th Cavalry after the Little Big Horn. Allied propagandists made hay of the Rape of Belgium by the inhuman Huns, but their German counterparts

vowed vengeances for the slaughter of their Knights in the Silver Helmets.

Such is the way of war.

No comments:

Post a Comment