|

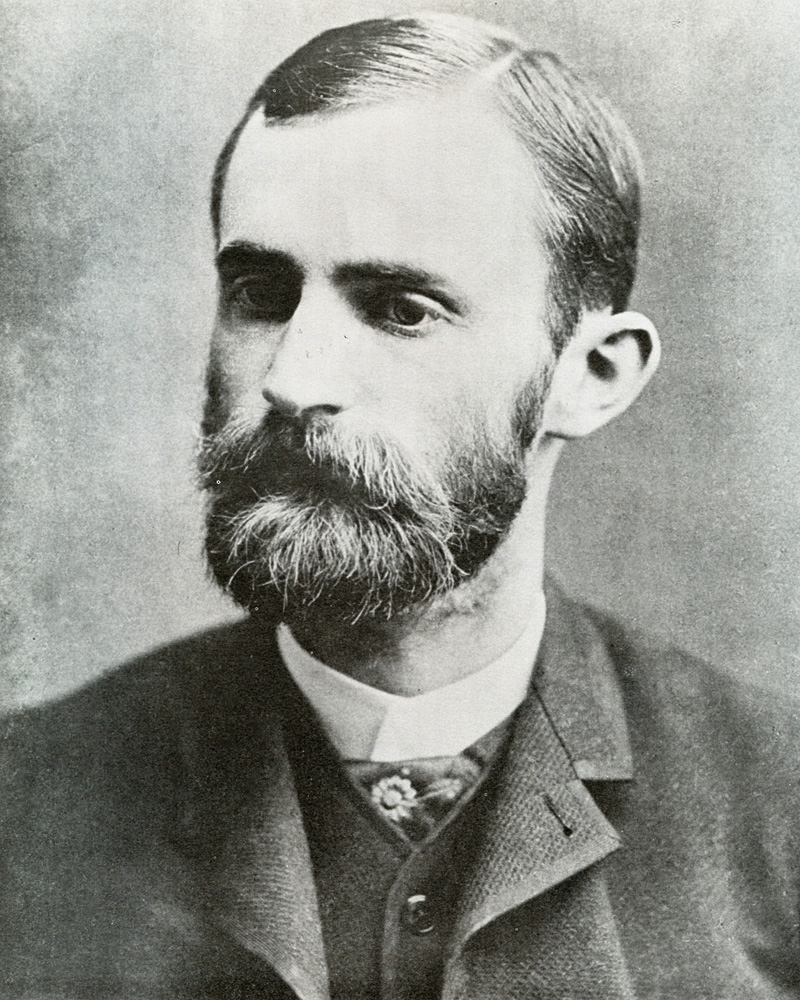

| Young George Eastman around 1880.. |

Until

George Eastman came along photography was a cumbersome process with bulky

equipment which required as much skill

at chemistry as on focusing the lens. It was reserved for professionals and very wealthy amateur dilettantes. Although the process fascinated the

public, each individual print image

was expensive. An individual or family

might sit once or twice in their lifetimes for a stiff portrait which became an

instant priceless family heirloom. Eastman changed all of that on September

4, 1888 when he was granted a patent for a box

camera that used the revolutionary

roll film that he had developed and patented in 1884. The same day he was granted a trademark his products—Kodak, a name developed by his mother to feature the letter K, “a strong, incisive sort of letter”

using an anagram generator. His instructions to his mother were that

he name be “short, easy to pronounce, and not resemble any other name

or be associated with anything else.”

Like

his inventions, Eastman’s trademarking and

marketing was groundbreaking and a

harbinger of a new era.

Eastman

was born on July 12, 1854 on a small, ten

acre farm near Waterville, New

York. He was the third and final

child and only son of George Washington

Eastman and Maria Kilbourne. The farm was essentially a summer get-a-way

place. His father had founded the Eastman Commercial College, a business school in the industrial boom town of Rochester in the 1840’s to train clerks, bookkeepers, and managers for the flourishing companies

in the town and region.

George

Sr.’s health began to fail and the family gave up the farm to move into

Rochester full time. The younger George

was educated at home by both parents until his father died in 1862. The school was forced to close and his mother

had to take in borders to support

the family. She eked out, a considerable

sacrifice, enough cash to send young George to a local private academy for his first and only formal education.

Eastman

was 16 when his middle sister Katie died

of polio. He left school to go to work to help support

the family. He was devoted to his

mother, who he viewed as having sacrificed her youth and life to support and

sustain the family. She in turn became

reliant on him and did nothing to discourage the devotion. Eastman would never marry, devoting himself

to his mother until she died in and then lavishing attention on his surviving

sister’s family.

In

the early 1870’s young Eastman found work in a local photography shop. He soon mastered the essentials and set up

his own successful studio. Like many young Americans of his era, he was

a tinkerer, always looking to find

ways of improving equipment and processes. He became obsessed with developing and alternative for heavy glass plates which were cumbersome and

limited the potential for the, e medium.

His

own experiments were not successful but in 1881, reviewing recent photographic patents, he found the work of Peter Houston, a Wisconsin farmer. His

brother David had filed and been

granted a patent for Peter’s development of roll film and a crude camera

to use it. The brothers did not have

the capacity to develop their invention.

He quickly bought the licensing

rights along with improvements to

the film and to a camera to use it which Houston developed later. In 1889 he would buy the Houston patents outright

for $5000. In the meantime Eastman made

his own improvements leading to his own 1888 patent.

Roll

film mounted photo-sensitive celluloid

strips with an opaque paper backing. The film was loaded onto a reel and then pulled across the back of the camera and fitted into a take-up reel. This allowed the film to be loaded in a lighted room or outdoors instead of in a dark

room or under a black-out hood

like a glass plate. After each exposure, the film was advanced on the

take-up reel until it was full of images.

The take-up reel could be removed and then developed and printed.

Kinks

had to be worked out in the camera, the most significant being reliably

advancing the film at set intervals to avoid double exposures and to prevent mishandling of the film to prevent

exposure while loading or unloading. It

wasn’t until four years later, in 1888, that Eastman perfected a camera to use

roll film.

|

| The first Kodak box camera complete with original packaging, carrying case, and instructions. Note the felt plug used to cover and protect the lens. |

His

box camera was elegantly

simple. It featured a single, fixed aperture lens and a single shutter speed. Film was advanced by turning a key on the top of the box attached to

the take-up reel between shots. There

was no view finder and the operator

was encouraged to line up shots by peeking over the top of the box. The simple lens and fixed shutter speed

eliminated complicated adjustment for amateur users and kept the cost of production to a minimum but that meant subjects needed

to be within a fixed focus length for maximum clarity, had to be relatively still—although nothing like the minute

long exposures of some glass plate cameras, and need to be shot in daylight, the brighter the better.

Eastman’s

target audience was not sophisticated

professional users—although he would develop cameras using roll film for them

in various size formats over time. He

was aiming directly for middle class

consumers and his business model was borrowed from safety razor baron King Gillette—sell the hardware cheaply at, near, or even below production costs and make

money on a monopoly on selling film

for the camera and for developing and making prints.

He

flooded the country with print advertising

touting his new product and sold the cameras for one Dollar. In an era when the

public was becoming enamored of new inventions and innovations including the telephone, electric light, gramophone,

and bicycles consumers were eager to

adopt modern gadgets.

Despite

brisk sales, a certain cumbersomeness of the Kodak system limited growth. The box cameras were sold pre-loaded with film sealed

inside. When the user finished the roll in inside he or she had to mail the entire camera back to the

Eastman plant in Rochester where the film would be removed, processed, and

prints made. The camera was reloaded

with new film and sent back to the customer along with their negatives and prints. That meant that the

camera was out of the users hands and unavailable for use for weeks at a

time. Wealthier families sometimes had

two or three so one was available.

The

cost of processing and film was fairly steep.

Users initially were very conservative in using their film. They also mostly modeled what they shot on

the work of professional photographers—stiff,

often grimly posed formal portraits of

loved ones. A user might take a year or

two, or even longer to fill a roll. The

era of the informal snap shot had

not yet arrived.

Still,

there were enough customers to rapidly make Eastman Kodak, formally established

in 1892, the largest manufacturer and employer in Rochester. His expanded line of more professional

equipment took off. In 1889 Eastman

developed and patented flexible

transparent film which the French Lumière

Brothers and their American competitor Thomas

Edison adapted for motion picture

film. Eastman was soon supplying the

rapidly expanding and booming new industry.

Eastman

also took advantage of an explosion of camera companies, each touting their own

specialties and improvements. Instead of

battling these potential competitors for

possible patent infringement in

court as Edison was constantly doing with film

and phonograph companies, Eastman

quickly produced film for each camera quickly turning his competitors into his

customers and unintentional business

partners.

|

| This Brownie model from the 1920's is the same one I used as a child. Note the two view finders to accommodate shots taken vertically and horizontally for the rectangular prints. |

Then

in 1901 Eastman introduced a major upgrade to his consumer box camera. He called it the Brownie after the popular fairies in magazine cartoons by Palmer

Cox. In fact Cox illustrated the

initial advertising for the cameras which Eastman promoted with the slogan, “You

push the button, we do the rest.” The

new cameras were still simple boxes, but customers now loaded their own film

and sent the finished reels to Rochester for processing, not the whole

camera. A simple view finder was added

so that shots could be more effectively lined up. 120,000 Brownies were shipped

in the first six months of production and sales continued to rise year by year

until by the time of the Great

Depression it seems that almost every American family had one and scrapbook albums of family photos were treasured keepsakes.

The

Brownie was improved many times over the decades. In 1928 a synchronized electronic flash attachment was added enabling indoor

and limited night time photography. In

the ‘30’s the old leatherette covered

box became a streamlined Bakelite case

with art deco touches. In the mid-‘50’s a built-in flash was

added. There were variations in size and

style, but the camera was still the main recorder of American home and family

life, and had been taken to war by GIs from the trenches of World War I to

Vietnam.

I

shot hundreds of pictures with the same box Brownie my mother had since the

‘20’s and my brother used an up-dated Brownie

Hawkeye, our pictures added to and filling new albums that my mother

carefully kept up as the official chronical of our family.

In

the ‘50’s the Brownie came under competition from the instant gratification of

the Polaroid. However novel, the Polaroid and its film were comparatively expensive and

you could not easily get duplicate

prints. Kodak competed with the

introduction of cartridge cameras—the

Instamatics that began to replace

the old Brownies in the late ‘60’s and ‘70’s.

The introduction ubiquitous Fotomat

kiosks in shopping center parking

lots which exclusively sold Kodak film and supplies, meant that customers

could have prints in 24 hours or often the same day instead of waiting a week

to “get back from the lab.” Automated photo labs or mini-labs that could be placed on-site

at pharmacies, groceries, and Big Box, cut typical processing time

to about 20 minutes in most stores in the ‘80’s.

In

the ‘90’s the introduction of the cheap pre-loaded cardboard disposable camera boosted Kodak sales while ironically

harkening back to the earliest days of the Box Camera when the whole thing had

to go to the go back to the lab.

But

rapid technological change was about to doom film cameras for all but specialty

and professional use. The rapid

introduction and improvement of digital

cameras, accelerating when cameras became a standard feature of almost all cell phones was a nail in the coffin of Eastman Kodak’s long successful business model. And as the market dwindled the shrinking

share of film was being hijacked by the Japanese

competitor Fuji Film which undercut Kodak’s prices across the board.

By

2010 Kodak had effectively exited the camera and film business to concentrate

on digital imaging and printing technology. It filed for bankruptcy in 2012, sold many of its business lines and patents,

and slashed its domestic manufacturing payrolls

to the bone. The company emerged from

bankruptcy last year after shedding

almost all of its consumer products. At

this writing it is desperately trying to save its one remaining film line—commercial motion picture stock by negotiating

new deals with the major Hollywood

studios and production

companies. Wall Street is betting

against them. Almost all of the shrunken

company’s business is now in printing equipment and services for business.

As

for that shrew businessman who started it all George Eastman, he prospered

mightily. By the early 20th Century he was one of the richest

men in America and an admired inventor/captain

of industry in the league with Bell,

Edison, Westinghouse, Firestone, and

Ford.

Unlike some of them, he operated his business on a high ethical standard, and was noted for his

fair treatment of his employees and rewarding them with relatively high pay. He

also started, at an early age, giving away more of his wealth than just about

anyone this side of Andrew Carnegie.

In

1901 as the Brownie was taking off, Eastman gave $625,000—the equivalent of

more than $17 million today—to the Mechanics

Institute, now the Rochester

Institute of Technology. In 1916 he

paid for the cost of the construction of the second campus for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He also generously endowed the Tuskegee Institute and Hampton University, both Black institutions in the South and several schools for the poor in major European

cities. In honor of his beloved mother and his own

passion for music—he was an accomplished pianist—he

created and endowed the Eastman School of

Music at Rochester University

and the schools of medicine and dentistry.

In fact public health was another passion, particularly often

neglected dental health. He opened

dental clinics for the poor in U.S. cities and in several European cities.

| George Eastman as a mature industrialist and philanthropist. |

On

a personal level, his life was not a happy one after the death of his mother,

for whom he grieved deep and long. As

noted he never married and made his sister’s children a surrogate family. His health began to deteriorate in the late ‘20’s

and he cut back his commitment to Eastman Kodak, leaving the Presidency to become Treasurer and concentrating on the firm’s

finances and investments.

In

his final years Eastman suffered from some sort of degenerative spinal condition which left him in great pain and

reduced his mobility until he was confined to a wheel chair. Even desk work became almost impossible and

he sank into a depression. On March 14, 1932 George Eastman put a bullet through his heart at age 77 leaving behind a note that read simply “To my friends, my work is done—Why wait? GE.”

Among

the generous gifts in his will, he

left his Rochester mansion where he

had frequently entertained friends with

concerts to the University of

Rochester. In 1949 the University opened

it as the George Eastman House

International Museum of Photography and Film, now an international famed

institution and the home important photography and cinema scholars.

Wonderful article. Thank you!

ReplyDelete