On

September 19, 1881 President James A.

Garfield died in agony on the Jersey

Shore 78 days after being shot in

the back by a disappointed office

seeker in a Washington train station. He had only been in office a total of 199

days, almost half that time incapacitated

by his injury.

One

of the bullets fired the

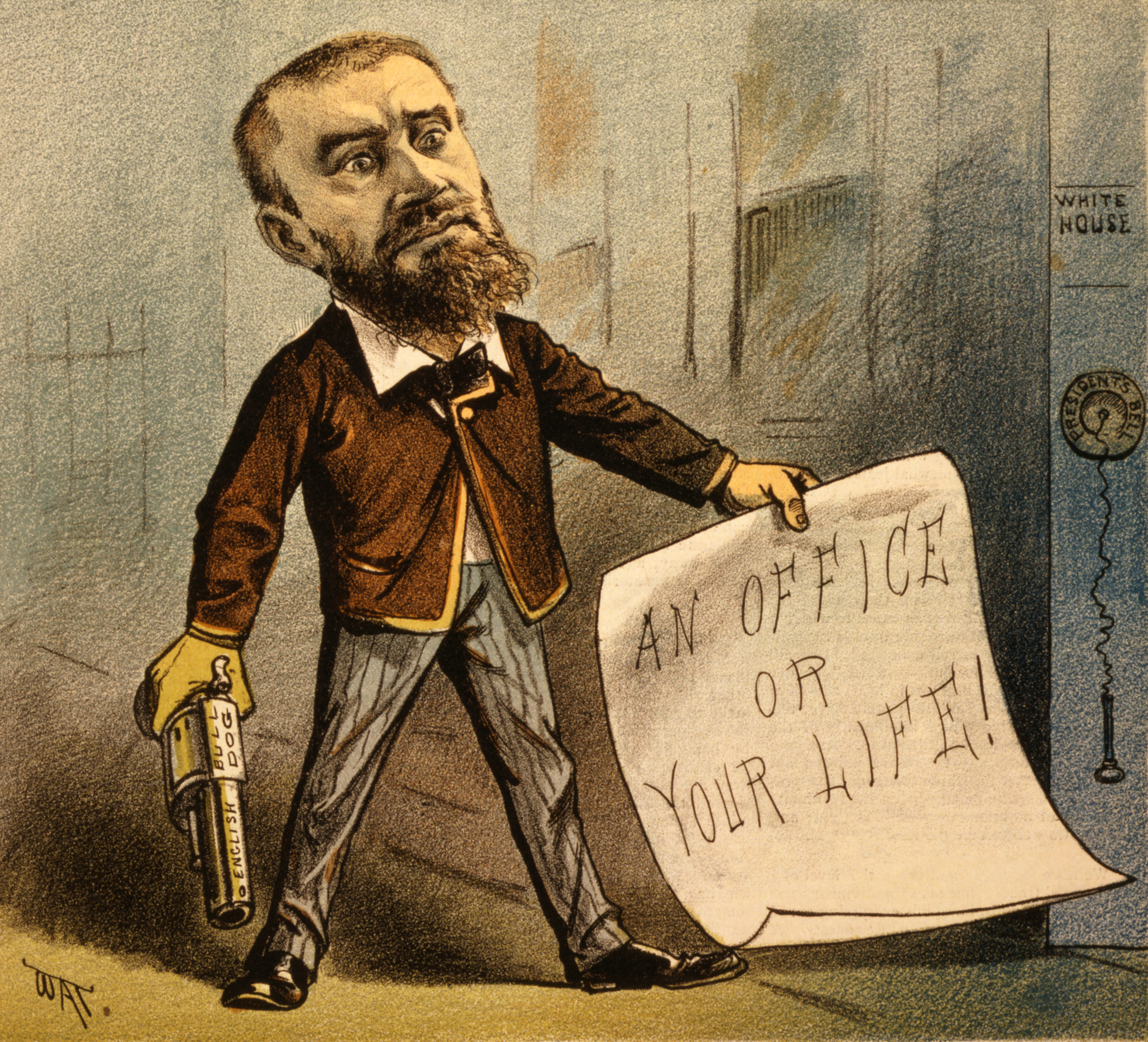

morning of July 2 by Charles J. Gateau grazed

the President’s arm. The other lodged in his back near the spine. It could not be found. But the search

for the bullet, rather than missile itself ultimately cost Garfield his

life.

Taken

back to the White House several doctors over the next few days probed for the bullet with instruments, and with their own unwashed hands—a bad practice even in those days.

One doctor even managed to pierce

his liver. The resulting infection, probably caused by Streptococcus, resulted in “blood poisoning,” untreatable in the days before antibiotics.

| Alexander Graham Bell tried to locate the bullet--it was lodged in the Presiden't spine--with his metal detecting magnetic devise. He was foiled by metal bed springs. |

Still

desperate to find the bullet, inventor Alexander

Graham Bell was called in. He had developed

a magnetic device to locate the

projectile. It would have worked,

too. But neither he nor the other

doctors realized that the bed on

which Garfield was lying had a metal

frame and springs—relatively

uncommon at the time—rendering the magnetic devise useless. Even if the bullet had been discovered,

however, the infection had already taken hold and it was probably too late to

save the President by surgery.

On

September 9, Garfield was taken by train to a beach home in Elberon

(now Long Branch) New Jersey in hopes that the sea air would revive him. It didn’t.

Garfield

was born in Moreland Hills, Ohio on

November 19, 1831. His father died when

he was small and he was raised by his mother.

A gifted student, he attended college

in nearby Hiram at a school maintained by his family’s Church of Christ (The Christian Church) denomination

before going east to complete his education at Williams College in Williamstown,

Massachusetts from which he graduated with distinction in 1856.

Returning

to Ohio he took up preaching at the Franklin

Circle Christian Church. He decided

against making a career in the ministry, but was ordained as an elder, making him the only clergy person ever elected

President. He remained a devoted church member the rest of his

life.

Garfield

married in 1858 and began supporting

his growing family as a teacher. Meanwhile he privately studied law and entered politics. He was elected to the Ohio State Senate as a Republican in 1859 and passed the bar the following year.

Garfield’s

rise to prominence began as a youthful officer in the Civil War.

He helped raise the 42nd Ohio

Volunteer Infantry Regiment and

was named its Colonel. Major

General Don Carlos Buell gave him a command of a mixed brigade of Ohio and Kentucky

Volunteer infantry and Virginia loyalist

cavalry. He helped clear Confederate forces out of western Kentucky and was promoted to Brigadier.

He was a brigade commander

at Shiloh and at the Siege of Corinth, Mississippi.

Pleading

health concerns Garfield asked for leave from the Army and was elected to

the U.S. House of Representatives. He returned to active duty until the new Congress was sworn in and served as Chief of Staff for William S. Rosecrans, Commander of the Army of the Cumberland.

After the Battle of Chickamauga

he was promoted Major General. In December, 1863 he resigned his commission to take his seat in Congress.

Garfield

quickly rose to prominence in the House

as a hawk on the war and for a harsh Reconstruction policy. He was handily re-elected every two years,

despite having been brushed by the Crédit

Mobilier scandal in which members of Congress were alleged to have taken

bribes to support the Union Pacific

Railroad.

In

1876 he was one of the appointed Republican

Special Commissioners that handed the Presidency

to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes

despite lagging Democrat Samuel Tilden in

the popular vote. The same year he became Republican Floor Leader of the House.

In

January 1880 Garfield was elected to the Senate

by the Ohio Legislature, which had just returned to Republican hands. He went to the Republican National Convention later that year pledged to support

the candidacy of fellow Ohioan John

Sherman. At the convention the

leading candidates, former President Ulysses

S Grant and Maine’s James G. Blaine,

were hopelessly deadlocked after multiple ballots. Grant’s partisans, the so-called Stalwarts represented a return to business-as-usual and an aggressive use of political

patronage. Blaine and Sherman represented,

to one degree or another advocates of Civil

Service Reform and were nick-named the Half

Breeds. On the 36th ballot, Blaine

and Sherman threw their combined support behind a surprised Garfield who won

the nomination.

The

election campaign, against another Civil War General, Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock,

was close fought. In addition the perennial issues of the pace

of Reconstruction and Civil Service,

Chinese immigration was a hot button

issue in California, a crucial swing state. Both candidates publicly opposed further

Asian immigration. A handwritten letter purporting to be from Garfield to an H.L. Morey of Massachusetts indicated

he supported unrestricted immigration. The firestorm

threatened to effectively derail his campaign until Garfield proved that the

letter was a forgery and that no H.

L. Morey existed. Public sympathy swung to the wronged Candidate. The popular

vote was tight—Garfield won by only 2,000 votes out of 8.89 million

cast—but he handily won the Electoral

College.

Garfield

spent the first months of his term trying to put together a Cabinet in the face of opposition from

Stalwart leader Senator Roscoe Conkling of

New York. Conkling had succeeded in

getting his protégée, former Collector

of the Port of New York Chester Allan Arthur on the ticket as Vice President, but he could not get the

Cabinet posts he desired for his faction, particularly the patronage rich

position of Post Master General. Garfield nominated Blaine as Secretary of State and Robert Todd Lincoln, son of the martyred President as Secretary

of War. He gave the Post Master

General job to a New York state rival of Conkling. Conkling and the other New York Senator

resigned in protest to the affront to Senatorial

privilege, but were surprised when the New York Legislature did not promptly re-elect them. After month of struggle, Garfield had

consolidated his power and defeated the Stalwarts. He finally was ready to turn to his

agenda—the passage of Civil Service Reform and the defense of suffrage for Freedmen

in the South. He never got to either

task.

On

the morning of September 19 Garfield entered the Sixth Street Station of the

Baltimore and Potomac Railroad for a trip to his alma mater Williams College where he was slated to

make a speech. He was accompanied by Blaine and Lincoln and

two of his young sons. He was shot in

the back by Gateau, who had fruitlessly been pursuing an appointment as a U.S. Consul in Paris, a job for which he was manifestly

unqualified. After he was subdued by

onlookers, Gateau told police that, “I am the Stalwart of Stalwarts! Now Arthur is President!”

That

led to brief speculation that the horrified Arthur or other Stalwarts

were somehow involved in an assassination plot.

Gateau, however, was quickly proven to have acted alone. After the President died, his lawyers tried

to defend him on the charge of murder by saying that the bullets he fired did

not kill the Garfield, his doctors did.

Fair enough, but the doctors could have never botched their treatment if

Gateau had not fired. A jury quickly found him guilty and he was hanged on June 30, 1882.

The

new president surprised everyone, including himself, by successfully pushing

Civil Service reform through Congress.

Arthur signed the Pendleton Civil

Service Reform Act into law on

January 16, 1883, a fitting memorial

to Garfield.

Robert

Todd Lincoln, who had endured the assassination of his father and was at

Garfield’s side when he was shot, was also in Buffalo, New York at the Pan-American

Exposition at the invitation of the President when William McKinley was shot in 1901.

He understandably felt he was something of a jinx and declined all

invitations to appear with other Presidents until the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in 1922. And that day, he was looking over his shoulder.

No comments:

Post a Comment