My

old home state of Wyoming has a lot

of memorable, iconic sights—the Yellowstone geyser Old Faithful, the

front range of the Grand Tetons,

Independence Rock on the old Oregon

Trail. But nothing is more unusual or more recognized than the formation

that looks like a giant tree stump

rising high above the winding Belle

Fouche River in a remote corner

of the state—Devil’s Tower.

After

10 years of futile efforts by the Wyoming

Congressional delegation to have a much larger area including the formation

declared a National Park on

September 24, 1906 President Theodore

Roosevelt, proclaimed Devils Tower as a National Monument. It was the first ever use of that designation. Only 1,152.91 acres of the originally

proposed park were protected.

Two

years later the rest of the abortive park in the drainage, including the nearby Little

Missouri Buttes, were opened for public use—a victory for both timber interests and cattlemen seeking yet more open range grazing.

No

one is exactly sure when the imposing feature was first seen by Whites.

Likely early trappers caught

a glimpse of it but accounts have not been found. In 1857 Lt.

G. K. Warren’s expedition to reach the Black

Hills from Ft. Laramie was

turned away from the area by a large party of hostile Lakota. Warren’s log

mentions seeing the Bear Lodge—one

of several indigenous names for the rock—and the Little Missouri Buttes in the

distance through a powerful telescope.

But some scholars believe, because he did not remark on it unusual

configuration, that he was probably referring the Bear Lodge Mountains also

nearby.

On

July 20, 1859 topographer J. T. Hutton and a Sioux scout, Zephyr Recontre

reached the formation. They were a small

party from the larger Capt. W. F.

Raynolds Yellowstone Expedition. But

once again neither Hutton nor Raynolds left a detailed account.

| |

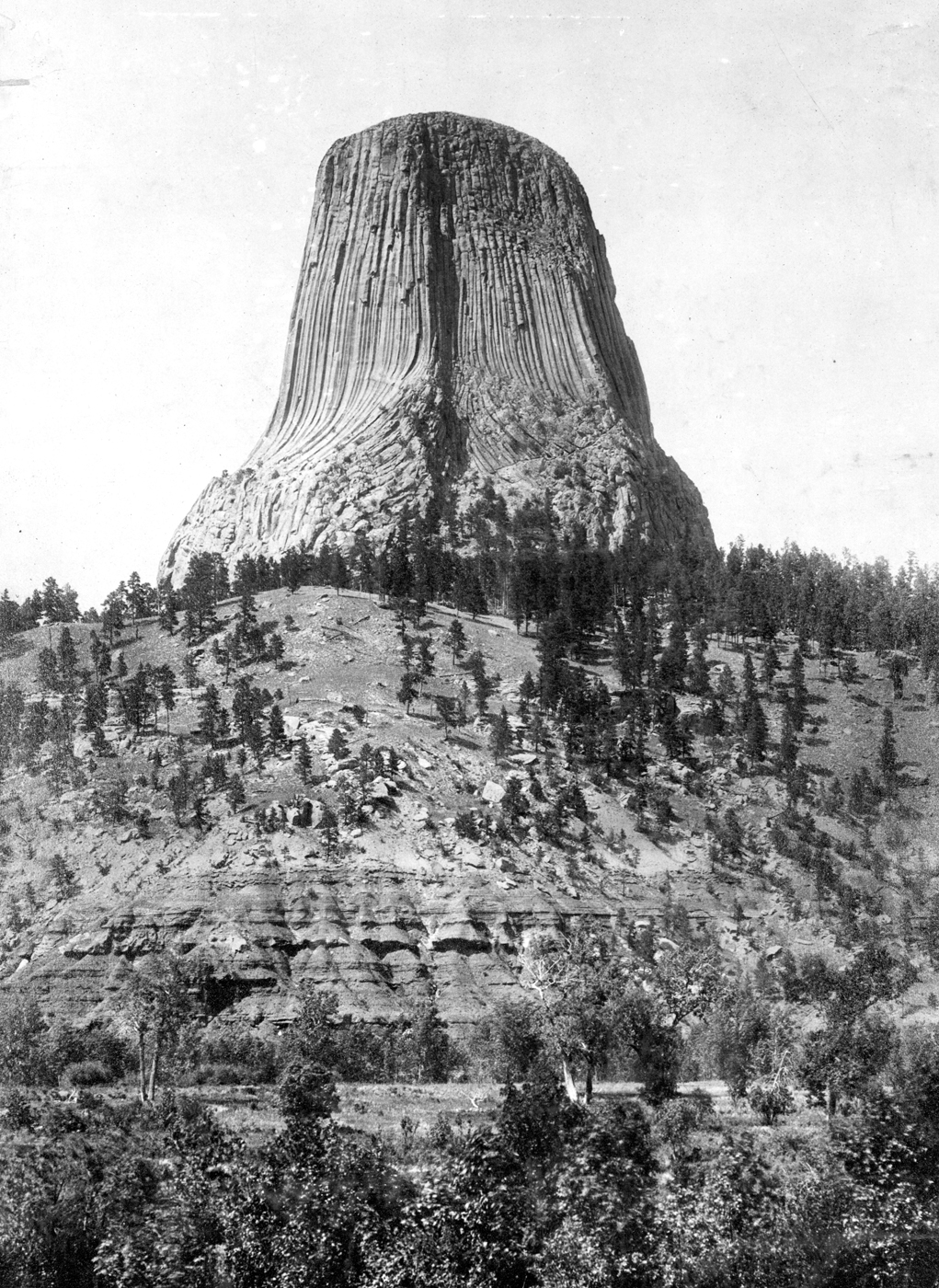

| An early photograph of Devils Tower circa 1900/ |

It

wasn’t until 1875 that a U.S. Geological

Survey expedition and its military escort under Col. Richard I. Dodge the formation was studied and described in

detail. Expedition member Henry Newt wrote:

Its remarkable structure, its symmetry, and its prominence made it an

unfailing object of wonder. . . It is a great remarkable obelisk of trachyte,

with a columnar structure, giving it a vertically striated appearance, and it

rises 625 feet almost perpendicular, from its base. Its summit is so entirely

inaccessible that the energetic explorer, to whom the ascent of an ordinarily

difficult crag is but a pleasant pastime, standing at its base could only look

upward in despair of ever planting his feet on the top.

Dodge was credited with giving the formation its

now familiar English name. As was so often the case, it came from a misunderstanding about a native name. An interpreter mistranslated one of the native names—most of which were some

variation of Bear’s Lodge in several different Plains tribe tongues—to Bad

God’s Tower. Expedition members

converted this to “Devil’s Tower.”

Following standard topographical

practice, the apostrophe was dropped from the official name given the

formation. We can be fairly certain that

the translation somehow went awry because none of the many native legends

associated with the rock have anything remotely to do with a “bad god.”

Of course Native tribes had been aware of the

Tower. It was considered magical or

sacred by many tribes—in addition to the Lakota and other Sioux the Arapaho, Cheyenne,

Crow, and Kiowa. The Lakota, the dominant tribe in the area

since their arrival from the East in the late 18th Century and spectacularly

successful adoption of the horse

centered Plains Indian culture,

regarded the Bear Lodge—Matho Thípila—as a sacred location second only to the Black

Hills.

The various tribes have

different origin stories for the great rock and many associations with mythic

figures or great heroes. Many

used the Tower as the site of individual cleansing rituals, group

spiritual practice such as the Sun Dance and Sweat Lodge purifications,

and as a sacred burial ground for heroes and great shamans. The Lakota associated it with one of their

most sacred objects, the White Buffalo Pipe, a gift of White Buffalo

Woman, a great spiritual mythic or semi-mythic presence.

Among the many legends

associated with the tower, the National Park Service, custodians of the

Monument, heavily promoted one story in their literature. In this tale, shared in slightly different

forms by the Kiowa and Lakota, seven Indian girls were playing or

gathering food near the river when a giant bear attacked them. The girls fled and ran to a large stump. They jumped on it and began to pray to the Great

Spirit (this language is a tip-off that the story has been laundered

through Whites and not collected directly from the people) for help. Hearing their prayers he began to raise the

stump to the heavens. As it grew and

grew, the enormous Bear tried to climb the stump leaving his claw

marks on the side and littering the base with the shredded

bark. The Bear could not reach the girls

and went away. But by then the stump had

grown so high that the girls could not climb down. Taking pity on their plight, the Great Spirit

transformed the girls into seven stars directly above the tower,

stars known to Europeans as the Pleiades. It is

difficult to tell know exactly how much of this popular story—I was entranced

with it as boy—are from authentic tradition, and how much grafted on similar

tales in Western mythology.

Today members of several tribes continue to hold

ritual observances at the Tower, although burials are now forbidden by the Park

Service.

It is also a popular tourist attraction,

although it takes a fairly determined tourist to get there. Located hours away from the nearest

attractions in the Black Hills, far from any town of even modest size, well

away from major highways, most visitors have to dedicate an entire day to

seeing just this one sight. There is

only one café at road junction miles away and a Park Service concession

stand on site for food. There are a

couple of 1950’s style motels nearby, a couple of dude ranches in

the area, and camping at Monument.

|

| Devils Tower became an alien landing place in Stephen Spielberg's Close Encounters of a Third Kind sparking new waves of visitors to the remote location. |

Yet people come.

Visits took a dramatic jump when Steven Spielberg featured the

Tower as the alien landing spot in Close Encounters of the Third Kind. And it has become a Mecca for the

growing sport of rock climbing.

Hundreds make the climb every season, as many as a dozen a day, using

several well established routes to the top on every side.

Native tribes, for home the site is sacred, objected

to any climbing. White climbers and the

tribes were at odds for years until the Park Service brokered a “voluntary”

compromise. Since most tribes hold their

holiest ceremonies at the Tower in June, the Park Service asked climbers to voluntarily

refrain from ascending the rock in that month. They estimate that 85% of climbers honor that

agreement. But authorities are powerless

to stop those who do not. And a climbing

group and local tourist interests have sued the Park Service for even

suggesting self restraint.

I visited Devils Tower several times as a boy. A few years ago when my daughters were

still children my wife and I made the long trip from the Black

Hills to show it to them. It was one of

the few natural wonders that they saw on the western trip that actually

impressed them. They even managed to

hike the trail that encircles the rock, quite an achievement for kids allergic

to walking.

No comments:

Post a Comment