|

| William Goebel's assassination at the Kentucky State Capitol in Frankfort. |

Kentucky Democrat William Goebel holds the dubious distinction of being the only American state governor to be assassinated in office. But even that claim to fame merits an asterisk. In the disputed

election of 1899 Goebel’s Republican

opponent, William S. Taylor had

been declared the winner in the official canvas by a scant

1,200 votes. Democrats alleged fraud and the matter ended up before the General Assembly which they controlled. That body declared Goebel the winner. Taylor refused

to accept the result. On January 31 as he was approaching the State Capitol in Frankfort on foot to be inaugurated

he was wounded in the chest by shots believed to be fired from inside the building. As the

State teetered toward actual civil war he was sworn in as governor on February 1, 1900 then died of his wounds on February 3.

Despite

the fact that many governors served during perilous

times and periods of social upheaval,

and despite the fact that more than a

few over the years have been scamps,

rascals, and outright thieves,

all the rest escaped with their lives if

not their reputations or freedom from prosecution. But in 1968 Alabama Segregationist George Wallace was shot and paralyzed from the waist down while campaigning

for the 1972 Democratic presidential

nomination. Survived and served out his term, was re-elected and then returned to the governor’s mansion for the third time

in 1983. When he died in 1998 his injury

was listed as a contributing cause.

A handful of governors were victims of

assassination or attempts after they

left office. Idaho’s Frank Steunenberg who was blown up with a bomb in

1905 in an infamous case in which Western Federation of Miners President

William D. “Big Bill” Haywood and union

associates were unsuccessfully

prosecuted. In 1935 Populist Democrat and/or demagogue Huey Long of Louisiana, then serving in the U.S. Senate and a thorn in the side of Franklin

D. Roosevelt and the New Deal was

shot in the ultra-modern capitol

building he had built in Baton Rouge

and died a few days later.

By contrast it seems to be much more dangerous to serve as President of the United States. Abraham Lincoln, James A. Garfield, William

McKinley, and John F. Kennedy were

all shot and killed in office. Andrew Jackson, Franklin D. Roosevelt (as

President Elect), Harry S Truman, and Gerald

R. Ford—twice—all survived assassination attempts un-injured. Ronald

Reagan was not so lucky and

suffered serious wounds when shot in 1981 just a little more than two months

into his first term but recovered.

Former

President Theodore Roosevelt was

shot in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1912 while campaigning to return to

the White House on the Progressive Party/Bull Moose ticket. The .32

caliber bullet fired at his chest at close

range was slowed by a folded 50 page typescript of the speech he was scheduled to deliver that

night and lodged in a rib. At his insistence, he made the speech talking for well over an hour before

finally seeking medical attention.

Today

assassination threats against the First

Black President, Barack Obama, come in daily—far

more than received by any other Chief

Executive. Most are hot air but an alarming number—the Secret

Service will not reveal how many—are considered serious or credible. Which is why many supporters feared and

many enemies hoped that he would not

live out two complete terms.

By

my calculations of the 43 men who

have served as President 10, nearly

a quarter were assassinated,

wounded, or targeted in verified

assaults before, during, or after their terms.

That

puts in perspective how unique Goebel’s case was.

|

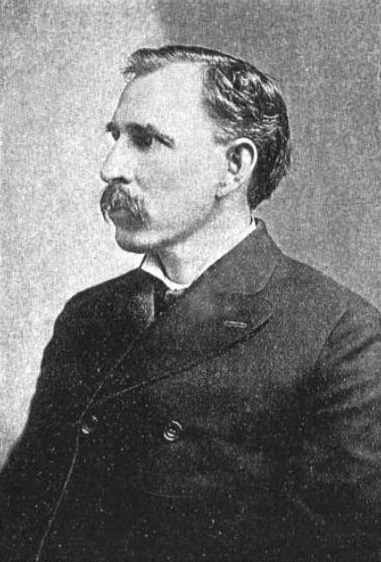

| The controversial William Goebel. |

Goebel

was a man of immense contradictions. Despite coming from hard circumstances and having little early formal education, he was regarded by his peers as a brilliant lawyer and

political tactician. Personally he was cold and aloof with

almost no true friends and never

known to have a relationship with a

woman. His stern, angular features were

described a reptilian. In an era that valued florid oratory

he could only be loud, hammering his points home with intellectual conviction. Despite utterly

lacking the talents of personal

connection to voters or charisma of any kind, he built a solid political career as a reformist populist, defender of working people, ally of labor, and ferocious opponent of railroad monopolies, political fixers, and the old conservative and aristocratic Bourbon Democrats who had dominated the state since

the Civil War. He could be highly principled but also ruthlessly

ambitious and Machiavellian. He abandoned

friends and betrayed allies for

political advantage. He was

simultaneously one of the most hated men

in Kentucky and had a large, devoted following among the common people.

He

was born Wilhelm Justus Goebel on

January 4, 1856 in Albany Township, Bradford County, Pennsylvania in the northeast part of the state not far from the New York border. His parents were immigrants from Hanover,

Germany and spoke only the mother

tongue at home. Wilhelm was the sickly and premature eldest of four children.

During his early childhood his father served for nearly two years as a private in the 82nd

Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry which saw hard service including the battles of Fair Oaks, Malvern, Antietam,

Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg.

After

the elder Goebel was honorably

discharged in 1863, he moved his family to Covington, Kentucky on the Ohio

River. Here the boy began his rapid assimilation as an American getting his first regular elementary education in English and Anglicizing his first name

to William. As a teen ager he apprenticed himself across the River in Cincinnati to a jeweler. But he had far higher aspirations.

After

taking classes for a brief time at Hollingsworth

Business College Goebel began reading law in the successful firm of John W.

Stevenson, who had served as governor of Kentucky from 1871 to 1877. Stevenson became a professional mentor and powerful early political

sponsor to the bright, hard-working,

and earnest young man. The young man pursued his formal

education at Cincinnati Law School

in 1877, then took classes at Kenyon

College in Gambier, Ohio.

For five years he was law partner to Kentucky state representative John G. Carlisle before rejoining Stevenson as

a full partner. The two were so close that Goebel was the executor of Stevenson’s estate when he

died in 1886.

Stevenson

was a conservative Bourbon Democrat who also served in the U. S. Senate, as the Chair of

the 1880 Democratic National Convention,

and was President of the American Bar Association when he

died. Despite this, after Stevenson’s

death Goebel began his steady rise in the Democratic Party as a populist

reformer.

In

1887 Goebel ran for State Senate on

a platform of railroad regulation and championing

labor causes. Despite this, he had the

backing of Stevenson’s old Bourbon associates.

He seemed destined to coast to an easy

victory until some labor leaders

created and backed the new Union

Labor Party with much of the same platform.

Goebel’s base was split. He eked out a meager 67 vote victory over the Union Labor Party and Republican candidates.

Once

in office he aimed at consolidating support of the Union Labor people by a

vigorous attack on the much hated, rate fixing Louisville & Nashville

Railroad. Shortly after his

election, the House of Representatives passed

legislation to abolish the already feeble state Railway Commission which had at least attempted to hold down ruinous freight rates. When the bill reached the Senate Goebel was

appointed to a committee to investigate railroad lobbying in the House which uncovered bribery, blackmail, and other irregularities. Armed with that scathing report, Goebel

led the successful defeat of the

bill in the Upper Chamber.

It

made him a hero and secured

re-election in 1889 and 1893 by increasingly wide margins. The Union Labor Party was re-absorbed by the

Democrats and the Republicans were trounced in Goebel’s district by a 3 to 1

margin in the latter election.

In

the interim, Goebel was elected as a delegate

to the 1890 Kentucky Fourth Constitutional

Convention. Although he had little

interest in much of the document, he personally led the fight to make the

Railway Commission as a constitutional

body which could only be abolished by a constitutional amendment approved by the voters, insulating that body from attacks in the legislature.

In

1895 came one of the most controversial

episodes in Goebel’s career—what may

or may not have been the last political

duel in American history, depending on how you define duel and whether or not you believe the fatal encounter was prearranged

or an accidental confrontation.

In

the legislature Goebel had won legislation to repeal tolls from some of the state’s turnpikes which had damaged

the business interests of banker and former Confederate General John Lawrence Sanford. The two men became bitter political

enemies. When Goebel’s name was advanced

to take a seat on the Court of Appeals,

then the state’s highest judicial body,

Sanford’s considerable political clout

had blocked the appointment. Goebel struck back in an anonymous newspaper article which called the old General Gonorrhea John, just the kind of slur on the honor of his name that an old

fashion Southern aristocrat could not stand.

On

April 11, 1895 Goebel accompanied by two men including the Attorney General of Kentucky encountered Sanford on the steps of

his bank. Sanford greeted Goebel’s

companions extending his left hand to

be shaken while keeping is right in

his pants pocket. He turned to Goebel and asked, “Are you

the man responsible for that article?” Goebel freely admitted it. Sanford drew a pistol from his pocket.

Goebel had been clutching his own gun in his coat pocket and drew it. The

men fired nearly simultaneously at very close range. The General’s shot went through Goebel’s

coat, grazed his vest, and ripped his pants. Goebel was

more accurate, his shot striking Sanford in the head and almost immediately killing

him.

The

incident caused an understandable

scandal. A coroner’s jury lead by the Republican

County Coroner, ruled that Sanford had fired

first and that Goebel had replied

in self-defense. Two attempts to indict him before a Grand

Jury on either murder or dueling charges failed. Under the Kentucky constitution conviction of participating in a duel would have barred him from public

office. Despite escaping legal consequences, the scandal was

used against Goebel by his political enemies for the rest of his life.

Despite

this the heavily Democratic state Senate elected Goebel to the power post of President Pro Tem in 1895 and he took effective control of that chamber enhancing his power be

supporting progressive candidates against long-sitting Bourbon Democrats.

In

his new position Goebel turned his attention election reform. In 1895 William O. Bradley had surprised everyone

by becoming the first Republican to

be elected Governor of Kentucky. A year

later Republican William McKinley

won the popular vote against

Democrat and Populist Party nominee

William Jennings Bryan. At the time election results were certified by county election commissions. Democrats

believed that the country controlled commissions in Republican areas had manipulated the count. Goebel successfully advanced the Goebel Election Law which created a three member State Election Commission with

members appointed by the General

Assembly to appoint county election commissioners. The bill had wide-spread support and became law when both chambers overrode the

Governor’s veto.

Goebel’s

power was now at its zenith.

Popular with voters his

enemies which now included both Republicans and besieged Bourbon Democrats derided him as Boss Bill, King William, William the Conqueror, and the Kenton King for his absolute control of

Covington’s Kenton County machine. Together these factions controlled most

of Kentucky’s main newspapers and

kept up a relentless attack on him, including charges that the new State

Election Commission controlled by Goebel Democrats in the General assembly

stacked the deck in the county commissions against Republicans and conservative

Democrats.

By

the election year of 1899 Bradley had proved himself to be a deeply unpopular

governor and declined to run for re-election. Democrats anticipated returning to

power. But three strong candidates sought

the party nomination—Goebel, Parker “Wat” Hardin, and William J. Stone. Hardin, the early favorite was a glib former

Attorney General who had twice before sought the governorship and who had the

strong backing of Goebel’s hated nemesis,

Louisville & Nashville R.R. Stone

was a popular ex-Confederate officer and Congressman

with a strong base in rural western Kentucky. All three men had blocks of delegates to the state

Democratic Convention in Lexington but

both Goebel and Stone trailed Hardin.

I

was then that Goebel entered an agreement with Stone. In exchange for releasing half of his Kenton

county delegation to Stone on the first

ballot—enough for Stone to win with the help of unpledged delegates—Stone

agreed to allow Goebel to select the down-ticket

candidates on the slate and

become de facto state party Boss.

But

when Hardin got word of the deal he unexpectedly dropped out of the race

and released his delegates. Goebel then

made a calculated decision to

secretly abandon the agreement with Stone and keep control of his delegates. Seeing

the opposition bloc broken, Hardin re-entered the race. He kept control of his delegates. No one was able to muster a majority through

several ballots. Then the Convention chair, a Goebel loyalist, announced

that the candidate with the lowest vote in the next ballot would be dropped from the contest. That turned out to be Stone. His supporters who also opposed railroad

influence held their noses and voted for Goebel to block Hardin. Goebel won the nomination, but at a heavy

cost.

|

| William S. Taylor claimed the Governorship after the 1899 election and may have been behind the plot to murder his bitter rival William Goebel. |

The

party was shattered. Many of Hardin’s

backers and some of Stones bolted and held a separate convention of Honest Election Democrats in Lexington

and nominated former Governor John Y.

Brown. In a three way race with

Republican William S. Taylor seemed

to narrowly win the popular vote. Goebel

trailed in second by only 2,383 votes in the original official canvas. But once

again charges of improprieties in Republican counties arose and the matter came

up before the very State Election Commission that Goebel had created and whose members

her had selected.

Surprisingly,

the Commission ruled in a 2-1 vote that the disputed ballots should be counted

because they had no legal authority to

overturn officially reported country results.

On the General Assembly itself had the power to do that. That ruling put the matter before the members

of the General Assembly. They invalidated enough of the disputed

ballots to swing the election narrowly to Goebel who was declared the winner.

Republicans

were outraged and refused to accept the decision. Many contemporary observers thought that the

state was teetering on actual civil

war. Taylor had assumed the

governorship and would not relinquish the title. Goebel determined to go on with his own inauguration.

Which

brings us back to that fateful January 1, 1900 where this story began. As he approached the Capitol accompanied only

by two body guards, five or six shots were fired from the building. One struck Goebel in the chest.

|

| Mourning the martyred Governor. |

Taylor,

still asserting authority as Governor himself declared a state of emergency and ordered the State Militia to Frankfort to both suppress protests and to prevent either the wounded Goebel or his Lt.

Governor candidate from being sworn into office. He also called a special session to convene in the Republican stronghold of London.

The Democratic members held their own session in Louisville.

The minority Republicans could not muster a constitutionally

required quorum. The Democrats

could.

In

the meantime Goebel was sworn in on February 2.

In his only official acts he ordered the Militia de-mobilized and

recognized his Lt. Governor J.

C. W. Beckham, who turned out to be too young to legally assume

office.

The

crisis threatened to continue. The

Militia did not heed Goebel’s order nor did Taylor withdraw. After Goebel died cooler heads decided that

Beckham would be an acceptable government.

A deal between Democrats and Republicans in the General Assembly was

struck that would recognize Beckham despite his youth, remove the Militia from

the Capital city, not pursue challenges to the election of down ticket

candidates, and give immunity to any officials implicated in Goebel’s

death. The latter was crucial because

suspicion was already turning on Taylor and his allies. All that was need was Taylor’s acquiescence. But he balked. Later, I am sure he regretted that decision. The Democratic majority went on to seat

Beckham. The matter landed in court.

The

Kentucky Court of Appeals upheld the

General Assembly’s action. The United States Supreme Court declined to

intervene on May 21, 1900. It was

settled. Goebel had been, however

briefly, the legal Governor and Beckham was his successor.

Without

protection from the amnesty in the original proposed deal, Taylor fled to Indiana where the Republican governor

refused to allow him to be extradited to

Kentucky.

Taylor

and 15 others were indicted for Goebel’s murder. Three of the accused turned state’s evidence. Five men were brought to trial and two were acquitted. Republican

Secretary of State Caleb Powers, Henry Youtsey, and Jim Howard were convicted.

Powers was accused of leading the plot and Howard, a farmer who had come

to Frankfort seeking a pardon for

killing a man in a family feud, was

the supposed triggerman. Youtsey, the accused middle man who

arranged the details of the hit, was sentenced to life in prison. After two

years behind bars he turned state’s

evidence.

That

was needed because the original verdicts were overturned due to

irregularities. At Powers’s second trial

Youtsey testified that he witnessed Powers and Taylor agree to proceed with the

murder and that he secured Howard to do the deed. Powers was tried a total of three times,

convicted twice more and got one hung jury.

Howard was convicted twice more before it stuck. Taylor could not be tried as long as he was

protected in Indiana.

Beckham’s

Republican successor formally pardoned Powers

and Howard in 1908 and Taylor, who never stood trial, a year later.

Historians

tend to believe that Taylor was at least aware

of a murder plot even if he did not personally approve it or participate in its planning. A minority believe he was the real victim in the whole sordid affair.

|

| Goebel statue at the Old State Capitol in Frankfort, Kentucky |

Today

Goebel’s assassination is memorialized with a plaque on the Old State Capitol building near where

he fell and a heroic statue standing

resolutely out front.

Goebel

remains a controversial figure in Kentucky to this day. How to teach

about his assassination is an issue in many school districts. He is

viewed as a hero and inspiration to Kentucky’s embattled liberal and progressive Democrats. On

the other hand he is made out as a tyrannical

villain by many right wingers and his killers

are portrayed as martyred patriots.

And

that speaks volumes about the state of Kentucky politics to this day.

No comments:

Post a Comment