Note—This is one of

those epic posts that took on a life of its own and required two days of intense

work to complete. I admit it’s too long

so I have broken it into two parts. Tune

in tomorrow for part two. This is

important stuff.

I

started, as I usually do by reviewing the

Wikipedia

On this Day…feature. I scan it in a daily search of just what the hell

to write about here. Two items

leaped off the screen and punched me

in the gut.

1877—The Molly Maguires, ten Irish immigrants convicted of murder,

are hanged at the Schuylkill County and Carbon County, Pennsylvania prisons.

1964—Three civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Mickey

Schwerner, are murdered in Neshoba County, Mississippi, by members

of the Ku Klux Klan.

At

first glance, these to items of historical

ephemera might seem to have little

in common occurring nearly a century apart to vastly different people under different

circumstances. But it occurred to me

that in some ways they are related, intertwined and even echo today in our chaotic and dangerous time.

You

may remember a sentence or two in your high

school American history book about

the Mollies—that they blew things up and

terrorized bosses in the Pennsylvania coal mines before be rooted out by a Pinkerton spy and given their just

deserts on the gallows. Those of a certain age and inclination

might recall the 1770 mega-budget

Paramount box office flop, The Molly

Maguires starring Sean Connery as

the tough miner bent on revenge for

a thousand injustices and Richard Harris as James McParlan the

conflicted but heroic Pinkerton

who befriends him and then betrays him.

The

shadowy Molly Maguires emerged in the anthracite

coal fields of eastern Pennsylvania in

the post-Civil War era when a rapidly industrializing nation relied

on the production of the mines for fuel and

to feed the insatiable steel blast furnaces.

Unable to find enough Yankee

farmers sons to descend into hell for

dangerous jobs with scant wages, mine owner increasingly

relied on immigrant labor—first the skilled and experienced coal miners of Wales

and Lancashire but ultimately on the

abundant unskilled displaced peasants of Ireland. Attempts to form a union, The Workers Benevolent Association (WBA), were led by the skilled American and Welsh workers were repeatedly squelched by mine owner violence and intimidation. Although as

many as 80% of the region’s miners, including the mostly Irish pit men who did the hardest and most dangerous labor, had little voice within the union largely

because the leaders shared the same disdain

of the Micks as their bosses.

Those

Irish miners died regularly in cave-ins and

explosions, who were cast aside like rubbish when injured or maimed, jammed into barely habitable shanties, in

perpetual debt to company stores, and subjected to cuts in their meager wages with every downward

economic tic—cuts that were never

restored when things began to hum

again. Yet they seemingly had no recourse.

But

they did have a tradition brought

with them from the Auld Sod. Over there a tradition of secret societies arose under the oppressive rule of the British, their imposed nobility and, large landlords. Called at various times and under various

circumstances Whiteboys, Peep o’ Day Boys and Ribbon Men these groups protested rack rents, evictions, and other injustices with frightening visits from masked

and disguised men, beatings, tar and feathering, and

occasional arson and murder.

Although hunted by authorities, strict secrecy avoided most prosecutions and the terror that they inspired in

local landlords often led to at least temporary

concessions and relief. In the rural environs of the big

cities like Dublin, Belfast, and Cork these groups also had nationalist

sympathies and character and

included both Catholic and Protestant tenants.

| The Whiteboys were one of several Irish secret societies that took revenge on landlords, tax collectors, and other oppressors. |

In

the rural and Gaelic speaking west

similar secret societies sprang up in the 1840’s in reaction to a wave of

evictions and in reaction to the wide spread misery of the Potato Famine. These groups

had little or no connection to the nationalist movement and were exclusively

Catholic and sectarian in as far as many big landowners were Protestants and Anglo-Irish. By 1845 there was a document outlining the

rules of a secret society being under the name title Address of “Molly Maguire” to her

children which was published in Freeman’s Journal. By the 1850’s and ‘60’s groups identified as Molly Maguires were

operating in Liverpool, the English destination of many rural laborers fleeing devastated Ireland and

the jumping off port for many Irish

immigrants to America.

Historians are divided on whether the Pennsylvania

miners brought a formal secret society with them and simply re-established it

in the new country or if the Mollies of Ireland and Liverpool inspired a copy cat movement as conditions in the

mines deteriorated during and after an 1873 Panic. Most suspect the

latter, although some men might have been involved in the earlier societies and

been familiar with their structures and oaths. Although episodes of violence

and retribution had been retroactively blamed on the Molly Maguires since the

mid-1860’s there had been a lull, almost extinction, of outburst until the

crash and subsequent depression.

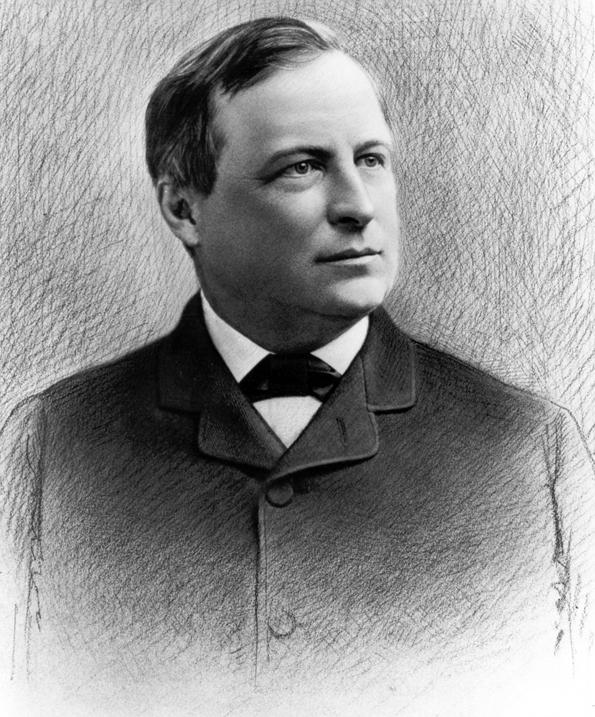

|

| Franklin B. Gowen, President of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Co.was the man behind plans to break the Union and stir up then smash the Molly Maguires. |

At the same time the major mine bosses united under

the leadership of Franklin B.

Gowen,

the President of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, and

of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and

Iron Company and decided to use the opportunity of widespread unemployment to break

the union at its weakest spot—the mistrust and hostility of the

conservative skilled workers for the Papist

Irish. To accomplish this Gowen

engaged the services of the Pinkerton

Detective Agency which had a well established

record of breaking unions. He

assigned the company to work with the Pennsylvania

Coal and Mine Police, a semi-private,

semi-official paramilitary police used to terrorize and persecute the

union and its supporters.

Irish

born operative James McParlan was

assigned to go undercover and infiltrate both the union and any

secret societies operating in the region under the alias James McKenna. McParlan, in

his detailed reports to his superiors, claimed that he easily gained the full

confidence of both Union leaders and certain Irishmen with influence over their

fellow workers. But he rued slow

progress—he was unable to make any connection to a secret society and violence

in the region continued its long lag.

That

ended soon enough with a sharp rise in assaults, and even murders. Some historians believe that at least some of

this violence can be attributed to Pinkerton and Coal and Iron Police activity

in order to arouse alarm about an alleged Molly Maguire threat. They point out that many of the victims were

leading union men and Irishmen who were painted as informers. The deaths of the

union men increased the alienation between the union leadership and the

Irish. Others believe that McParlan and

other agents acted as agents provocateurs goading miners

into the violence. A minority of ideologically business friendly historians

totally buy McParlan’s claims that

he eventually ferreted out a major

conspiracy without contributing to it.

| Pinkerton spy James McParlan in the 1880's. |

McParlan

identified a secret organization with the Ancient

Order of Hibernians, an open and legal benevolent

society similar to many others established by immigrant groups. He inferred That the AOH and the Mollies were

in reality one and the same organization and acted in concert with the Union to

attack its enemies. Others believe that

the miners used the cover of the Hibernians, who could meet openly, to conduct

the separate affairs of the secret society.

The trouble is no trace of that secret society, not a single document,

confirms the existence of the Mollies or another society. The AOH, which is still in existence, has always

stoutly denied that their Pennsylvania lodges and the Molly Maguires were

associated. All we do know is all of the

men eventually arrested and charged via McParlan’s investigation were members

of the Hibernians.

McGowan,

according to documents, decided to force the union into a strike which began on

January 1, 1875 and then break it by a combination of brute force by the Coal

and Iron Police, and dividing the men along ethnic lines. Alan Pinkerton himself suggested the

formation of vigilantes to attack

supposed and identified Mollies. After a

spate of killings and assaults, including the suspicious murders of union men,

a vigilante group did stage an attack on a home killing one man and one woman

and wounding two who got away. The house

had been identified by McParlan in his reports as belonging to a Molly. The spy, however, was so outraged that the

vigilantes had used his intelligence to kill a woman, that he angrily turned in

his resignation. Pinkerton mollified him

with claims that they had not shared his information and was induced to stay

on.

Meanwhile

the Coal and Iron Police arrested and imprisoned most of the union leadership on

charges of conspiracy in May. By July miner’s families were starving and

vigilante attacks on union men were spreading fear. The strike was broken and the men forced to

return to work with a devastating 20% pay cut.

McParlan

noted that only after the strike did many rank-and-file

Irish miners swing their allegiance to the supposed Molly Maguires. Even after continue attacks by vigilantes,

the Mollies were slow to respond.

McParlan, now claiming to have “infiltrated their inner circle,” likely

egged on plans for revenge. Finally

there was a spate of killing attributed to the Mollies.

| Four of the accused Molly Maguires are marched to their execution on June 21, 1877. |

Based

on McParlan’s testimony a number of men were arrested by the Coal and Mine

Police. Three men accused of killing Benjamin K. Yost, a Tamaqua Borough Patrolman, went on

trial separately. One, James Kerrigan,

who was the brother of McParlan’s fiancé,

turned state’s evidence and implicated

three more men. Franklin Gowan

personally prosecuted the cases which hit a snag when Kerrigan’s wife testified

that he had committed the murder and had tried to save himself by pinning it on

innocent men. The trial ended in a

mistrial. At a second trial Mrs.

Kerrigan was mysteriously unavailable to testify and all five men were

sentenced to hang while Kerrigan was set free.

McParlan’s

testimony also resulted in the conviction of five men in other cases. In all ten men were sentenced to hang. The sentences were carried out in two groups

on June 21, 1877—six men were hanged in the prison at Pottsville, and four at Mauch

Chunk in Carbon County under the protection of heavily armed Pennsylvania Militia.

But it was not over. Ten more

men were hanged over the next year.

Labor

“peace” was thus restored in Pennsylvania coal fields—at least until the rise

of the United Mine Workers and the

work of Mother Jones led to new

campaigns—and suppressions—in the 1890’s and beyond.

McParlan,

celebrated as a great hero in the popular

press, had a long career with Pinkerton, by the turn of the century he was

in charge of western operations out

of the Denver office. He employed cowboy/gunman Tom Horn who killed ten men and a boy for Wyoming cattle barons at war with small

ranchers. Horn was famously hanged, but

McParlan and the Pinkertons escaped blame for the murders. Later he famously Kidnapped Big Bill Haywood and two other officer of the Western Federation of Miners and

transported them in sealed train from

Denver to Idaho to serve time for

the bomb murder of ex-governor Frank Steunenberg in 1905. But his plan to frame

the men for a conspiracy was foiled by defense attorney Clarence

Darrow. They were acquitted and the

actual, undisputed bomber, known as Harry Orchard who had been induced

by McParlan to implicate them, was convicted of the murder.

Tomorrow Part Two—The Mississippi murders of

Andrew Goodman, James Chaney, and Mickey Schwerner.

No comments:

Post a Comment