Eighty years ago on November 23, 1936 a

new incarnation of a familiar name hit American newsstands and launched a new era of print journalism centered on the stark power of the still photograph. For almost 40 years LIFE, a slick, oversize magazine was a weekly

visitor to millions of homes and

a unique chronicle of a dramatically changing world and

nation. Say what you will about

publisher Henry Luce—and there is a

lot of bad stuff to say—but he had a phenomenally

good idea.

Life was not a new name in publishing. A

magazine by that name was inaugurated in New

York City, by John Ames Mitchell and Andrew

Miller in 1883 modeled on the successful British humor magazine Puck

and its American incarnation. Mitchell handled the business end and Miller,

a successful commercial artist in

his own right, handled the editorial

content. From the beginning Life became known for its dazzling cover

art and interior illustrations, enhanced by lithography techniques using .

zinc coated plates |

| The 1000th number of the original Life in 1921 featured a nostalgic look back a a trunk full of old issues. |

When Charles Dana Gibson, creator of the Gay ‘90’s iconic Gibson Girl, became a regular

contributor—and eventually an owner—the

magazine took off and became one of the most popular in the country. Other noted contributing illustrators including

Palmer Cox, the creator of the Brownie

and W. E. Kemble who was the

original illustrator of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn but who contributed popular, but degrading Coon

cartoons to the magazine. Later Life

became an early home for Norman

Rockwell.

This

incarnation of Life became known for

it furious anti-German slant as it tried

to push the reluctant President Woodrow Wilson into joining the Allies in World War I. It also had a nasty anti-Semitic streak.

None-the-less, it remained popular, even when post war tastes changed,

by adding reviews of Broadway productions

and films. When the upstart

New

Yorker was launched, it stole

many Life features, including its

short reviews, and raided the staff

of many key players. By the time the Depression hit, circulation

was dwindling and advertising

revenue plummeting. The staff kept it going until Henry Luce

made an offer they couldn’t refuse.

|

| Publishing tycoon and Time-Life founder Henry Luce with his influential wife, playwright Clair Booth Luce. |

Luce was not really interested in buying the

magazine. He just wanted to buy the name. The simple

one word title worked will in the tradition

of Luce’s other publications, both

phenomenally successful, Time and Fortune. Luce wasted

no time in firing the staff and selling the magazine’s subscription lists, features, and goodwill to the

original magazine’s chief competitor

Judge.

The first issue of

Luce’s LIFE, now a news weekly

built around photographic coverage—a newsreel

on the printed page—featured a cover

photograph of the Fort

Peck Dam on the Missouri River in Montana by the soon-to-be-famous Margaret Bourke-White. Inside was a five page spread by Alfred

Eisenstaedt another shutter bug

to become synonymous with the

magazine. The magazine displayed its

photos and accompanying text on high

quality, heavy slick paper and

sold for just a dime making it affordable to even Depression era

readers.

The formula

was an instant success. Circulation soared from an initial 380,000

copies to over a million in just four months.

Such success naturally spawned imitators, the most successful being Look,

a virtual clone, which came out a

year later.

The editorial

policy of the magazine was pure Luce—virulently

conservative, an opponent of the

New Deal and Franklin Roosevelt and viciously

anti-labor. Yet whatever the editorials and

texts said, the power of the

pictures snapped by the world’s best

photo journalists often worked

against the stated objectives of the

management.

Edward K. Thompson,

who began as an assistant photo editor

in 1936, influenced the magazine through a succession of increasingly important posts, including photo editor, managing

editor and eventually editor-in-chief

until his retirement in 1970. That

spanned almost all of LIFE’s

existence was a photo weekly. Under his leadership—and perhaps at the insistence of the publisher’s wife Clair Booth Luce—LIFE offered opportunities for women unmatched at other publications. Bourke-White, for instance, became one of

seven female correspondents who

covered World War II. Among the others was Mary Welsh Hemingway, wife of novelist/correspondent

Ernest Hemingway. Women also rose in editorial leadership. Thompson gave extraordinary autonomy to fashion

editor Sally Kirkland, movie editor Mary Letherbee; and modern

living editor Mary Hamman.

LIFS’s

coverage of World War II

cemented its place in American life, giving the folks on the Home Front an often unvarnished view of what their loved

ones were going through. It dispatched

reporters and photographers to every

theater of the war, including those like Burma, the Aleutians,

and Italy that were often ignored in other media. Among those covering the war was veteran war

photographer Robert Capa, whose

photos of landing in the first wave of D-Day

at Omaha Beach were the only pictures from that perspective to survive. Capa continued

to cover conflicts around the world for LIFE

until he was killed by a landmine in Vietnam in 1954. At war’s end, Eisenstaedt captured one of the most iconic images of the age—a

celebrating sailor sweeping up a young nurse for a passionate kiss in Times

Square on V-J Day.

|

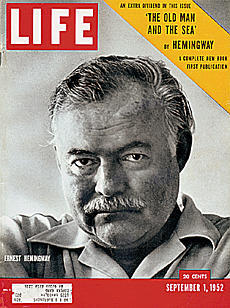

| Ernest Hemingway was a regular contributor and The Old Man and the Sea, the short novel which led to his Nobel Prize was first published in LIFE. |

In the post-war years LIFE added

to its prestige by publishing serialized versions of the memoirs of President Harry S. Truman, Sir

Winston Churchill, and General

Douglas MacArthur. Top

literary figures including John

Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingway also contributed. Hemingway first published The

Old Man and the Sea in the magazine’s pages and latter turned in a

10,000 word essay on Spanish bullfighting.

In

the 1950’s LIFE chronicled the rapidly changing American landscape. Although its fierce anti-Communism was

supportive of Senator Joe McCarthy,

the unforgiving cameras of its

journalists captured the alcoholic

crusader at his most menacing. The magazine may have endorsed the return to

normalcy of the post war nuclear

family, but it also captured women at work and teenagers in rebellion. It

showed pictures of busty starlets

and hip-shaking rock and rollers, as well as grim scenes from the Civil Rights Movement. Luce might have endorsed Richard Nixon for President in 1960,

but John F. Kennedy and his photogenic wife leapt off the pages.

LIFE’s coverage of the Kennedy assassination and the nation in mourning may have been its high water mark. It rushed

a quickly produced hardbound

commemorative book to press by December, which instantly became a treasured memento in millions of homes.

In

the ‘60’s Gordon Parks and others

documented the civil rights movement and eventually the emergence of the new

militancy of Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam, and the Black Panther Party. The magazine celebrated the triumphs of the space program including the Mercury,

Gemini, and Apollo missions. It might

have spurred interest in psychedelic drugs when it published a generally

positive article on Magic Mushrooms,

by a New York advertising executive which led Sandoz Labs to isolate and patent psilocybin to add to its portfolio that already included LSD. It also showed the dark side of heroin addiction in a series of photo-essays that inspired the film

Panic

in Needle Park. A new generation

of war correspondents captured the bloody

horror of Vietnam while others captured brewing rebellion in the streets.

But

with the growing competition of television,

LIFE’s fortunes were on the wane.

In the late ‘60’s the magazine geared

up expanded coverage of Hollywood and

celebrities to lure readers. Emblematic was the coverage of Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton’s hot romance on the set of the epic Cleopatra. The generous

use of more and more color

photography crowded out traditional black-and-white photos on the

magazine’s interior. Both moves boosted sales, but the magazine was, depending on who was telling the story,

either loosing money or becoming unattractive to advertisers interested

younger readers.

Time-Life pulled the plug on the weekly

in 1972. Two years later it launched People,

supposedly inspired by the popular

section of the same name in flagship magazine Time, but also picking up the tradition of photo-heavy celebrity

coverage from the last days of LIFE.

LIFE was still a valuable name. The publisher

issued occasional LIFE Special Reports such as The Spirit of Israel, Remarkable

American Women and The Year in Pictures from

1972-1978. The continuing brisk news

stand sales of these special editions

helped bring about a rebirth of the magazine as a monthly in 1978. For the

next 22 years it bumped along as a moderately successful general interest

magazine. High points of this incarnation included a special 50th anniversary issue featuring reproductions of every cover of the

magazine, a brief four issue return to weekly publication as LIFE

Goes to War during the 1991Gulf War,

and a series on the most important

people and most important events

of the millennium.

Deciding that the days of the general

interest magazine were over, Time-Life killed the magazine again in 2000 to

concentrate on a gaggle of newly

acquired special interest niche magazines like Golf, Skiing, Field & Stream, and Yachting.

LIFE would have one more ignominious revival as regular

periodical. From 2002-2007 it was

converted into a weekly newspaper

supplement to compete with well established Parade and USA

Weekend. The flimsy rag was barely a ghost of its illustrious past. By the time it was unceremoniously discontinued, it had shrunk to twenty 9½ x 11½ inch

pages of celebrity twaddle.

LIFE lives on, sort of, as a

web page. Agreements with Google and Getty Images

have made the magazine’s archives,

including hundreds of thousands of unpublished

photographs available on line. And

the LIFE name continues to be used for special issues.

No comments:

Post a Comment