|

| Indigenous Resistance--Alcatraz Occupation and #NoDPLN at Standing Rock. |

Note: The

ongoing struggle of the Standing Rock Sioux with the united support a Native

Nations across the U.S., Canada, and Latin America as well as indigenous people

from across the globe to stop Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) and irreparable damage to the Missouri River

drainage is just the largest and most recent of ongoing attempts of Native

peoples to reassert their rights since their military conquest was completed

within a few years of the Wounded Knee Massacre. Among the most dramatic of these episodes was

the seizure of Alcatraz in San Francisco Bay.

Here is that important story.

On

the face of it the property was not very attractive. In fact it had serious issues. Stuck in the

middle of San Francisco Bay it was typically damp and cold, shrouded often by that famous

fog. Access by

boat from the shore was difficult and inconvenient. The property was largely occupied by hulking, ugly

abandon buildings sinking rapidly

into disrepair and perhaps haunted by generations of human sufferings that had gone on within their

walls.

None-the-less,

on November 20, 1969 a rag-tag and barely organized group of Native Americans, most of them local college students, dodged Coast Guard boats to land on Alcatraz Island and claim it in the name of all Indian people by virtue of the Right of Discovery and provisions of the Ft. Laramie Treaty of 1868 which reserved the right of the Native

Nations to claim all unused and surplus Federal Government

property.

| Alcatraz Island including the Coast Guard Light House and the abandoned Federal Prison cell block and out buildings. |

Alcatraz

certainly fit that bill. The rugged

island named for the pelicans

that roosted there by the Spanish

came into the possession of the United States Government after the Mexican War. A costal

defense fortification was erected and garrisoned in the 1850’s. Not

long after, the first operational light house on the West Coast was built on its high

point. During the Civil War the Fort doubled as a prison for

the first time housing Confederate sympathizers

and agents, and the crews of Rebel privateers captured by the Navy. After the war the defenses were considered obsolete and the facility became an official military prison in 1868

housing soldiers convicted of crimes

and deserters. Later some Native American “renegades” were also detained there beginning with some Hopi men in the 1870’s. After the San Francisco Earthquake in 1906 civilian prisoners from the city were transferred there for safe

keeping.

Designated

as the main Army prison for the West

Coast, an enormous new modern,

multiple story cell block was erected over the subterranean first floor of the former citadel and opened in 1912. During World War I Draft evaders and conscientious objectors joined the

military offenders. The military prison

was decommissioned in 1933 and

transferred to the Department of

Justice. The following year the Bureau of Prison re-opened it as maximum security facility housing prisoners who continuously caused trouble at other federal prisons. Among

its inmates was a who’s who of hardened criminals including Al Capone—slipping rapidly into syphilis induced dementia—George “Machine Gun” Kelly, Bumpy Johnson, Puerto Rican Nationalist Rafael Cancel Miranda, Mickey

Cohen, Arthur “Doc” Barker, James “Whitey” Bulger, and Alvin “Creepy” Karpis.

There

were no successful attempts to escape the island, although several men

died trying either by being shot in the

attempt or drowning in the

treacherous waters of the Bay. Shortly

after a particularly bloody botched mass

escape attempt in 1962, Attorney

General Robert F. Kennedy ordered the prison shut down and most of its prisoners transferred to the new maximum security prison at Marion, Illinois in 1963.

The

island was soon deserted except for

the Coast Guard lighthouse. Its

buildings had been rapidly deteriorating

for years in the damp, salty conditions

of the bay. Without constant attention

they quickly got worse. Although the old

prison became something of a tourist

attraction, with tour boats

circling it, the government had no clear

plans for its future use.

It

first attracted the attention of

local Indian activists in 1964. On March

8 of that year 40 Sioux activists

led by Richard McKenzie, Mark Martinez, Garfield Spotted Elk, Virgil

Standing-Elk, Walter Means, and Allen Cottie occupied the island for

four hours, laying symbolic claim to

it under the Fort Laramie treaty but generously

offering to pay the government 47 cents per acre or $9.40 for the entire island,

the same price offered Red Cloud for

the vast tracks of land ceded in the

1868 treaty.

The

idea continued to percolate in the

Native American activist community, especially at Bay Area campuses where Indian students began organizing inspired by the Civil Rights Movement.

| The iconic image of the occupation by Ilka Hartman--young Native Americans raise the Red Power fist salute on the Alcatraz docks. |

Adam Fortunate Eagle, a 40 year old Ojibwa first conceived of a new occupation of Alcatraz. He encountered Richard Oakes, a 30 year old Mohawk

who had helped found the Native American

Studies Department at San Francisco State University, at a party.

The two, soon joined by Shoshone

Bannock LaNada Means, head of the Native

American Student Organization at the University

of California, Berkeley, began

to plan another occupation and Oaks recruited

students from groups on several campuses.

On

November 9, 1969 boats that were

supposed to transport demonstrators to the island failed to appear. Fortunate

Eagle somehow convinced the owner of the

sailing yacht Monte Cristo, then giving tours

of the Bay, to take on the protestors and sail by Alcatraz Island. Oakes, Cherokee

Jim Vaughn, Inuit Joe Bill, Ho-Chunk Ross Harden, and Jerry Hatch jumped overboard, swam to

shore, and claimed the island by right of discovery. They were quickly removed by the Coast Guard but later that day 14 others made it to the island and

managed to camp out overnight before

being ejected. When Fortunate Eagle

presented an official document to

the General Services Administration

(GSA) in San Francisco that day demanding that the island be turned over to

the United Tribes it made headlines across the country.

Organizers

then began planning a permanent

occupation.

That

effort was launched in the pre-dawn

hours of November 20 and involved 79 native activists, most of them

students but also including some married

couples and six children. An alerted Coast Guard prevented most of

the small boats transporting them from landing but 14 made it to shore

including Oakes, Means, Bill, and David Leach, John Whitefox, Ross Harden,

Jim Vaughn, Linda Arayando, Vernell

Blindman, Kay Many Horse, John Virgil, John Martell, Fred Shelton,

and Rick Evening.

| Blackfoot longshoreman Joseph Morris, rented space on Pier 40 to transport supplies and people to the island. |

This

time no effort was made to dislodge the

occupiers and despite the harassment

of the Coast Guard over the next several days the number of occupiers swelled.

Some of these early arrivals played key

roles as events played out. Blackfoot

Joe Morris was a member of the Longshoremen’s

Union, a group with a long, storied,

and proud radical heritage. He was instrumental in having the union announce that it would launch a general strike of the docks if attempts were made to remove the Indians. This was an excellent insurance policy. He

also later rented space on Pier 40 to facilitate the transportation of supplies and people to the island.

Sioux John

Trudell quickly became a public

spokesman of the movement and began broadcasting

Radio Free Alcatraz, daily

reports to the Berkley campus FM radio station.

Cleo Watterman, a Seneca, was President of the San

Francisco American Indian Center, and stayed

on shore to organize broader support

and to help collect and forward supplies and provisions as the population on the

island grew.

Grace Thorpe, the daughter of legendary athlete Jim Thorpe, used her wide connections with Hollywood celebrities, to drum up star power support. She was aided by jazz singer Kay Starr, and Iroquois

born on a Dougherty, Oklahoma reservation. Jane Fonda, Anthony Quinn, Marlon Brando,

Jonathan Winters, Cree Buffy Sainte-Marie, and Dick Gregory were all enlisted to visit the island and show their support. Thorpe also personally donated a generator,

water barge, and an ambulance service to the island. She was instrumental in getting a $15,000

donation from Credence Clearwater Revival

which was used to purchase the Clearwater which provided reliable, safe service to the

island.

A highlight of the early period of the

occupation occurred on November 27, when the first Unthanksgiving was thrown attracting

hundreds of day visitors. Two days later

a sympathetic Bureau of Indian Affairs employee,

Doris Purdy came and shot a short film.

President

Richard Nixon appointed

his Special Counsel, Leonard Garment to take over negotiations from the GSA. He was instructed to concede nothing on the Indian claims under Treaties and to try and get them off the island without provoking a

crisis. Talks were not successful.

Meanwhile

sympathy for the occupation was rising. Press coverage was generally positive.

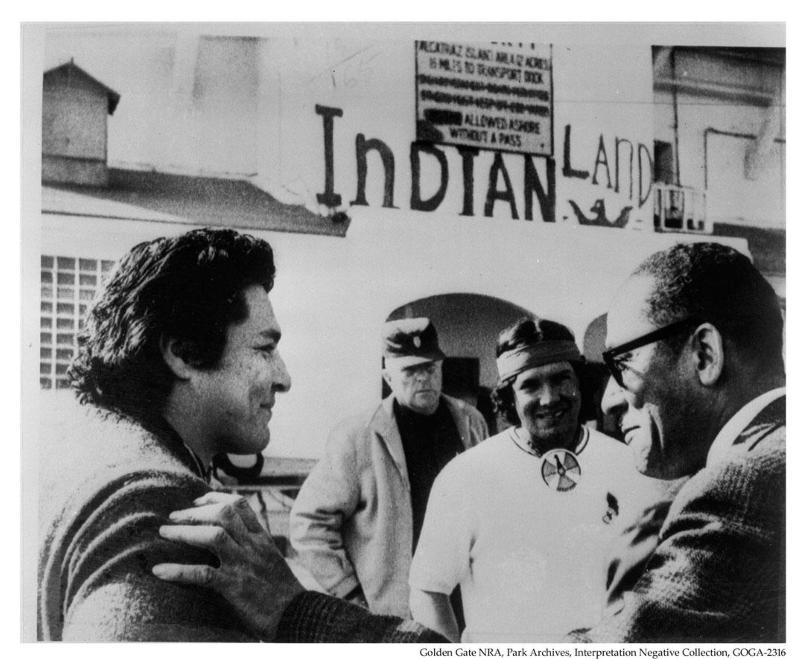

|

| Mohawk Richard Oakes was one of the planners of the occupation and a key leader in the early days withdrew after his 13 year old daughter died in a fall from a wall. |

However

after the first of the year, things began to deteriorate on the island.

On January 3 Richard Oakes’s 13 year old stepdaughter Anne fell to her death from a wall. The heartbroken Oakes and his wife Yvonne withdrew from the island leaving

something of a leadership vacuum

which Means, Trudell, and Stella Leach

strove to fill. Means, who was more

comfortable with the press than many of the others, became the most publicly visible spokesperson for the movement,

although she soon found herself facing

internal discord.

Several

of the original occupiers departed to

return to school. Meanwhile the

population, which at one point reached nearly 400, swelled with many of the

Native American homeless, including

those with drinking and drug abuse problems. Incidents of violence

between residents increased as did harassment

and sexual attacks on some women.

White supporters had been

welcome, but several street freaks moved

in brining increased drug use. Leaders tried to counter with increased self-policing and a ban on non-Indians staying overnight.

Bob Robertson, a Republican working for an outfit called

the National Council on Indian

Opportunity arrived in January.

Means and some of the others thought he was an unofficial emissary from Nixon authorized to conduct back channel negotiations. He proposed turning the island over to the National

Park Service with a promise that some kind of Indian Cultural center and continued

access for events. This was entirely unsatisfactory to almost

everyone, but Means met privately with

him and three lawyers to solicit a $500,000

grant to renovate facilities on the Island.

Robertson considered the attempt extortion

and some of the other Native leaders suspected Means was fishing for a sinecure administrating

the grant. Robertson turned down the

proposal and left the island.

Means

also hoped that if the United Tribes could secure a top-notch, high profile lawyer to sue the Federal Government for

possession of the Island under the provisions of the Fort Laramie treaty, they

would have a good chance to succeed. She began traveling from the island to raise funds for such a suit and to

look for a hot-shot lawyer to take

the case. In here absence rumors circulated, including that she

had been offered a screen test and a

movie contract.

Trudell

and the occupiers local lawyers objected to Means’ plans. The majority of occupiers backed

Trudell. Means and many of her

supporters withdrew from the island.

Sensing the

discord

on the Island, in May the government stepped

up pressure by turning off electricity and water service and increasing harassment

of supply boats. Living conditions on the island began

to deteriorate rapidly.

| The warden's house, the keepers' quarters and other buildings burned under suspicious circumstances, undermining public support. |

In

early June fires of suspicious origins

destroyed four historic buildings on the Island. Footage of black smoke drifting over the Bay

made for dramatic television and the

previously sympathetic press began turning

on the occupiers. Numbers on the

Island began dwindling down to a hard

core.

On

June 11, 1971, a large force of

government officers removed the remaining

15 people from the island. Despite

the problems the occupation lasted 19

months and inspired a wave of more

than 200 acts of Native American civil

disobedience, including an attempted take-over of an abandoned Nike missile site a few days later by

some of the occupiers.

They

also raised public sympathy for the Native American rights and land

claims. They have been credited with influencing the shift in administrative

policies away from away from termination

of reservations and toward recognition

Indian autonomy. Leaders of

subsequent actions including the Trail

of Broken Treaties, seizure of the Mayflower replica, the BIA Washington Headquarters occupation,

the Wounded Knee incident, and the Longest Walk were all inspired by the

Alcatraz example.

In

1972 Alcatraz became a National

Recreation area and received designation as a National Historic Landmark in 1986. Today, the island’s facilities

are managed by the National Park Service as part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Park Service interpreters include discussion

of the occupation on their tours and signs of it still remain.

And

every year Native Americans hold and Unthanksgiving dinner on Alcatraz.

No comments:

Post a Comment