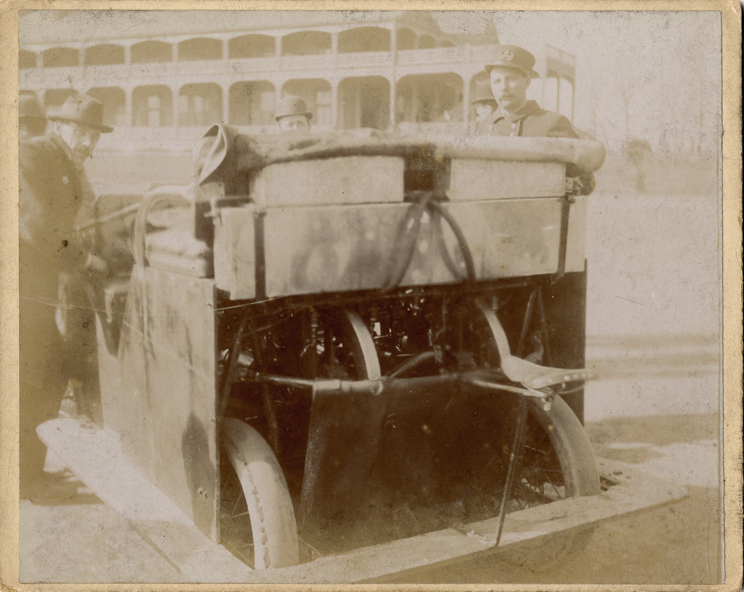

| Frank Duryea in his Motor Wagon, winner of the Chicago Times-Herald Thanksgiving Day Race in 1895, the first ever in the U.S.A. Note the slush on the streets. |

The

first automobile race in the United States was held in Chicago on Thanksgiving Day, November 28, 1895.

Chicago

was always a tough newspaper town. A half a dozen or more daily papers scrambled to survive, in the shadow of Joseph Medill’s Chicago Daily Tribune. In 1895 the Chicago Times, a struggling Democratic paper in a city dominated by Republicans since the Civil

War, had recently merged with

another also-ran in the newspapers wars,

the Chicago

Herald.

H. H. Kohlsaat, publisher of the new Chicago-Times Herald was looking for

a way to build circulation and

challenge the mighty Tribune. Looking around for something new and

exciting, they hit upon those new-fangled

horseless carriages that various tinkerers

were beginning to produce by hand in

tiny shops. Most people had never seen one and those who had found them noisy and ridiculous looking. Hardly anyone thought there was a future in them. But in a country that had recently undergone

the revolutions of electrical and telephone services, nothing could be dismissed out of hand.

On

July 9, 1895 the Times-Herald announced

that it would give a whopping $5,000 to

the winner of a Moto-cycle race between Chicago and Milwaukee. The hefty

prize indeed stirred interest. Over

80 entry applications were turned

in, many of them for cars that had not

even yet been built or were still under

construction. Originally slated for late summer, a number of problems

caused a series of postponements.

|

| The final route of the race from a 1945 50th anniversary account of the race. |

First,

there proved to be no good route to

Milwaukee. In an era when trade between the cities was conducted

by rail and Lake Michigan freighters, there was no single road connecting the two cities. Various routes

patched through country lanes proved, even in August, one of the driest

months of the year, to be muddy and impassable. The route was changed to at 54 mile round

trip from what had been the Palace of

Fine Arts at the 1893 Columbian

Exposition (now the Museum of

Science and Industry) and the northern

lakefront suburb of Evanston.

The

race was rescheduled for November 2,

but had to be delayed again because

hardly any entrants had arrived in

Chicago. Most entrants could not finish their autos in time, others

could not get them transported. One was damaged

in route. Then entrants arriving in the city in

their cars were stopped by police. City ordinances

forbad self-propelled vehicles on the streets. Drivers had to hitch their automobiles to teams

of horses to enter the city.

The

race had to be delayed again as Time-Herald

lawyers frantically lobbied the

city to change the law. Finally, with city approval obtained, the race was given a go-ahead for Thanksgiving.

| Three Benz Velos, considered the world's first production automobile, were entered in the race and were the heavy favorites. One finished the course well behind Duryea. |

Six vehicles made it to the starting line. Three of them were manufactured in Germany by Karl Benz. The German had

patented his Motorwagen, the first vehicle powered by a gasoline fueled internal combustion

engine in 1885 and by 1894 was producing his Velo model,

considered the first mass produced

automobile in the world. It were

Velos with 3 horsepower engines and a pivoting front axle controlled by a tiller that were entered in the race Two vehicles were electrically powered by storage batteries.

The final entrant was a Duryea Motor

Wagon built by brothers Frank and Charles

Duryea, bicycle mechanics in Chicopee,

Massachusetts

with Frank at the helm. The vehicle was

just the second completed by the infant company.

Conditions the day of the

race were not good. Several

inches of snow had fallen overnight

and temperatures hovered just around

freezing, giving drivers a challenge of fresh drifts in some spots, icy

ruts on city streets, and slushy mud

in the country.

The

race got underway at 8:05 a.m. with Duryea in the lead. The electrical vehicles found their batteries drained by the freezing

temperatures and were quickly out of the

race. One of the Benz autos hit a horse and was also out. Duryea was in a comfortable lead when he skidded in the icy street and snapped off his tiller. It took more than hour to locate a blacksmith and have him re-forge the end of the tiller and thread it to fit. The remaining Benz vehicles passed him, but

he regained the lead at the turn in

Evanston.

On

the way back, near Humboldt Park, one of the two cylinders in the Duryea engine stopped firing and Frank had to tinker for an hour. Not realizing that the faster of the two

remaining Benz autos was out of the race, Duryea struggled through heavy snow, but claimed never to have had to get out and push.

Near

the finish line he was held up by a frantic search for gasoline, which was sold only in small quantities at pharmacies

for use as a cleaning product. Then he was held up for more than five

minutes by a freight train. Duryea finally crossed the finish line at 7:18 p.m. having completed

the route in seven hours and

fifty-three minutes at an average speed of 7 miles per hour. The

remaining Benz crossed the finish line an hour and a half later. No other vehicles completed the race.

The

race succeeded in selling newspapers—but not enough to stave off the collapse of the final successor to the Times

Herald before World War I. The race generated national publicity and led to a surge in American auto innovation and production. The quarreling Duryea brothers continued

to manufacture Motor Wagons through the end of the century selling almost 300

of them. After that each continued to produce cars separately. Frank produced his with gun maker Stevens Arms for a few years. Charles continued his production until 1917

by which time more modern machines had

made his obsolete.

No comments:

Post a Comment