|

| The Rev. Joseph Tuckerman. |

With all due respect, Jane Adams,

move over. Adams, the legendary founder of Hull House in Chicago is popularly

credited as the original American social worker. That was never

quite true, although she did help

make it a profession. Nor did she

quite invent the settlement house concept for serving the

needs of immigrants, although Hull House certainly set the standard.

Decades earlier a Unitarian minister was doing similar work in the slums of Boston.

Although nearly forgotten

today the Rev. Joseph Tuckerman

probably deserves the title of the First

Social Worker.

It did not seem a likely career path. Tuckerman was born to a very comfortable family, a part of the Boston elite, on January 18, 1778. His father was a successful merchant and the founder

of America’s first fire insurance company. As

expected of a young man of his class and

prospects, he entered Harvard where

he shared rooms with young William Ellery Channing, who would go

on to be viewed as the founder of

Unitarianism as a distinct

denomination, and Joseph Story,

later the very distinguished Chief Justice of the Massachusetts

Supreme Court and revered

legal scholar.

|

| Tuckerman's life long friend, mentor, and sposnsor, Rev. William Ellery Channing in a 1815 portrait by Gilbert Stuart. |

Tuckerman did not seem destined for such lofty accomplishments. Channing later recalled that his dear friend

was at best an “indifferent scholar”

who used his three years at Harvard as “a holiday.” In some ways a typical rich man’s son.

After graduation in 1798 he eventually turned to the ministry, a respectable

occupation that probably seemed to him to be less arduous than the law or business. With an independent

income from his family, he could live

comfortably, if modestly, on the

sometimes meager pay of a small town

pastor.

After studying with some other ministers, Tuckerman accepted the not

terribly desirable pulpit of the church in Rumney

Marsh—renamed Chelsea—a quiet farming community and fishing port. He served

the congregation there faithfully for 25 undistinguished years. Unlike ambitious

ministers, he did not publish

volumes of his sermons or angle for

a call to the more prestigious

pulpits in Boston and its immediate environs.

He did seem extraordinarily interested in the ordinary seamen who called

at the port and the struggling

families of those who made their homes there. This population, thought to be incorrigible drunkards and including aliens and Papists,

were not usually either sought out

by or served by respectable pastors and their congregations.

In 1824, probably at Channing’s urging, Harvard bestowed a Doctor of Divinity degree on Tuckerman

for his long service in

Chelsea. Two years later, his voice ravaged by the demands of two long sermons every Sunday and mid-week lessons and lectures,

he had to resign his pulpit and retire from active preaching.

In 1826 Channing, on behalf of an ad

hoc group of Boston ministers

operating as the Association for Mutual

Improvement, invited the newly unemployed Tuckerman to assume direction of a new mission to the poor of Boston.

In 1825 Channing and most of the

Boston ministers had recognized that the

split between the orthodox and liberals in the New England Standing Order was irreconcilable

and formed the American Unitarian

Association (AUA) to promote

Unitarian missionary work. It was soon, de facto, the uniting and organizing force behind the

liberal Boston area preachers. The AUA

soon took responsibility for

Tucker’s new mission.

Money was raised from contributions by wealthy Unitarians and by appeals to local congregations to pay

Tuckerman $600 a year. Not a princely sum, but not out of line with the poorer pulpits. Fortunately in addition to his own family

income he had inherited from his wealthy first wife and his current wife also brought income to the family.

Not only could Tuckerman and his wife live in proper style in Boston, it would turn out that he had enough money to self-fund many of the ambitious projects he soon undertook.

If Channing and his friends thought

that Tuckerman would be a place keeper

and that the job was a form a charity

for him they were wrong. The suddenly energized clergyman had found his calling and meant to do it right.

Boston at the time was undergoing a transformation from a mercantile center populated mostly by

the decedents of Puritan colonists, to a bustling

commercial and manufacturing hub. The first

waves of largely impoverished immigrants were filling the poorer neighborhoods.

They were shabby, ignorant,

noisy, riotous, drunken, and Catholic,

all traits that made them unwelcome in respectable Congregations. But the ministers of those congregations and

the leaders of local society feared

that if not in some way tamed by a dose

of proper religion, they would infect

society as a whole. They wanted

their Minister-at-Large to find a way to

instruct them without having to admit

them to their own congregations.

|

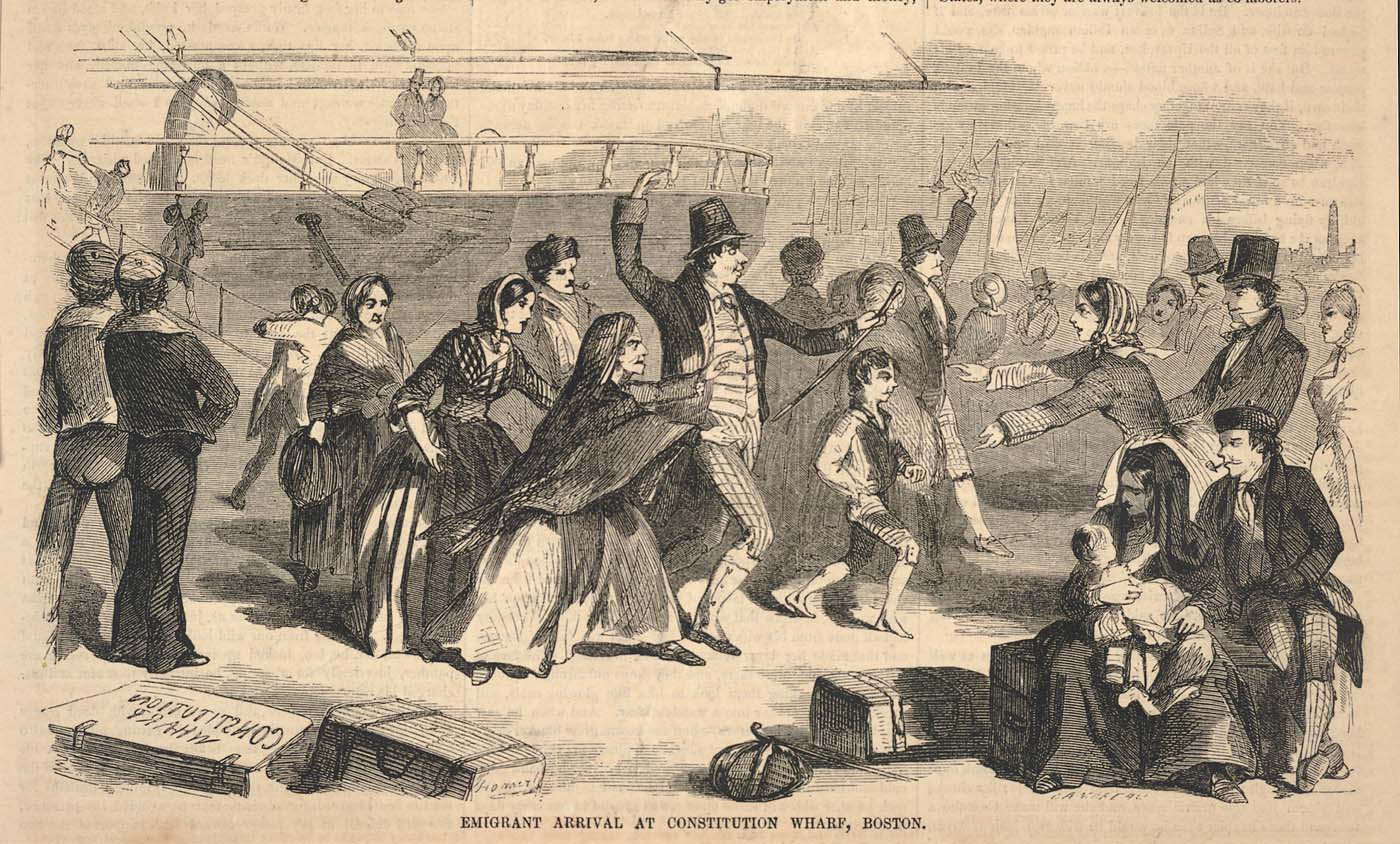

| This depiction of Irish immigrants arriving in Boston by Winslow Homer was more sympathetic than the simian brutes often depicted. |

Tuckerman studied the most advanced European

social philosophers and familiarized himself with experiments in social services in England and on the Continent. He also took

seriously the prevailing Unitarian idea of salvation through self improvement. But he came to realize that the immediate needs of people would have to be

met before they had the time and inclination for it. He began a scientific study by observation of the conditions of their lives.

Neither his sponsors nor Tuckerman

at first had a good idea of how to

proceed. He began roaming the the slightest bit of attention

to their wretched lives. He began to

win trust with small acts of streets in the port

districts where most of the poor were crowded. He walked

up to folks whose shabby dress identified

them as targets, introduced himself, and began talking. He invited

himself into their homes, asked

questions, and took notes. Some of his targets were flattered that any of the gentle

class paid charity like the purchase

of cord wood to warm a frigid hovel,

warm clothes, or a meal.

As confidence in him grew, he began to invite the children of immigrants to attend a Sunday School with him. He rented a small room over a paint shop in the Circular Building at the corner of Portland and Friend Streets

for those classes and Sunday evening

lectures for the parents—often concentrating on the evils of alcohol.

By 1828 the response was so good that he was outgrowing the rented rooms.

Encouraged that Tuckerman might have found a way to taming the beasts of the slums the AUA raised $2000

to build a new chapel on Friend Street. A second one was built on Pitts Street in 1834, and Tuckerman’s associate Charles Barnard opened a third one aimed mostly at children in

1837.

By that time hundreds of children

were enrolled in Sunday schools and hundreds of adults regularly worshiped at

the Chapels. Some even came to think of themselves as Unitarians. But despite

this success, AUA ministers were unwilling

to trust these new faithful to be admitted

to membership in their congregations, and were not even willing to turn over the chapels to them so that they

could have their own self-governing

congregations. Despite Tuckerman’s occasional protests, the AUA was determined to do “good work” while treating the unwashed as virtual colonies.

In the early years each local

congregation offered some sort of help

to the poor, however meager. Some

congregations did more than others.

Sometimes there were duplications. Tuckerman campaigned to unite all of these efforts under a central administration for record keeping and fair allotment of resources.

In 1834 the new Benevolent

Fraternity, a consortium of

Unitarian churches, took over responsibility for the ministry-at-large from

the AUA and Tuckerman added the administrative tasks to his

responsibilities.

Known as the Ben-Frat, the new organization grew to five chapels and a full array of social services over the balance of the Century. In fact it survives to this day, now known as Boston’s UU Urban Ministry.

In addition to charity, education,

and missionary work Tuckerman used his position to publicly espouse numerous reform proposals. Like many of his colleagues he was a strong Temperance advocate, but unlike them did

not consider drunkenness to be a moral failing, but recognized it as a disease.

In addition to campaigning to

reduce the opportunities to drink, he sought ways to medically treat alcoholics. He

campaigned for public education and

urged the creation of what would become truant

officers to compel parents to send

their children to school. And in

those schools he opposed corporal

punishment and harsh discipline

which he recognized would only encourage

truancy. He urged that chronic truants and delinquents be sent to farms for rehabilitation rather to jails to learn to be hardened criminals.

In fact Tuckerman spent a lot of

time visiting jails and juvenile detention centers ministering to the inmates and trying to find them safe and productive places when they got

out.

Throughout the 1830’s the strain of his work took a toll on

Tuckerman even after he was relieved of

some duties with the support of Bernard and another minister, Frederick T. Gray. He went to England and to regain his

strength in 1833 where he formed

friendships with Lady Byron, Joanna Baillie, and Raja Rammohun Roy, Hindu reformer and founder of the liberal Brahmo Samaj sect.

His examination of British public

charities for the poor—debtor’s prisons

and work houses—houses of horror well documented by Charles Dickens, convinced him that government run charity was inherently miserly, cruel, and punitive. He believed that only Christian charity and private

relief efforts could effectively and

justly service the poor, so he publicly campaigned to end what few public charities there were in Boston.

Tuckerman wrote extensively. His reports to the AUA and Ben-Frat boards are detailed treasure troves of information on urban life of the

period. He regularly published articles in the press, mostly

calls for various reforms. In 1838 he

published his great summary of his work,

The

Principles and Results of the Ministry-at-Large in Boston which became

a kind of text book for social workers

of future generations, including

Jane Adams herself.

|

| Tuckerman's grave at Mt. Auburn Cemetery, resting place of the Boston Unitarian elite. |

His health now completely broken,

Tuckerman had to retire from the Ministry-at-Large that year. In 1840 friends convinced him to make a trip to Cuba with one of his daughters for the Cure. The Cure, as it often

was, was more dangerous than the disease.

Havana was a hot bed of tropical

illness including Yellow Fever

and Malaria. Soon after arriving there in relatively good

health, he fell ill and quickly died.

His great and good friend Channing elegized him.

No comments:

Post a Comment