Tom Skilling, the WGN TV weather maven and something of a

local folk hero really, really hates Groundhog Day. Old

Chicagoans now tune in just to see if his head really does explode this year, which annually seems more likely as he has grown fatter year by year.

Sadly for him, it is a losing

battle. Instead of withering under scientific scorn and the weight of irrefutable evidence, Groundhog Day continues to grow in popularity and spread every year. From an obscure

folk custom observed by a handful

of German immigrants and their decedents in isolate pockets of Pennsylvania

in the late 18th and 19th Centuries it has spread nationwide.

Now that Trump is in the White House plump rodent stands a good

chance of being appointed head of

the National Weather Service.

In

2015 Wikipedia

identified no fewer than 38 woodchucks

dragged from their winter

hibernation and exposed to the sky across the U.S. and Canada. Come hell

or high water virtually every news

broadcast in North America today,

including Skillings’s own WGN, will feature

stories about one or more of the creatures

and whether he—almost always identified

as a male but most frequently a she—will

see his shadow supposedly signifying six more weeks of winter weather.

These

local observations got big boost with the release of the movie Groundhog Day starring Bill Murray and Andie MacDowell in 1992. The

film has become a beloved classic with

a cult following often compared to Frank Capra’s It’s A Wonderful Life.

It was filmed in my neck of the woods, as another TV weatherman used to say, in Woodstock, Illinois. Just after 7 am Woodstock Willie will make his grumpy

appearance from the Gazebo as he

has every year since the film came out.

The city has stretched the

celebration into a week-long

festival in hopes of luring pilgrims

and tourists. It works.

The Woodstock ritual is now

the second-most famous celebration

in the country behind the original at

Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, which the McHenry

County town portrayed in the film.

|

| The film Groundhog Day was filmed in Woodstock, Illinois and hyped interest in the pseudo holiday. |

This

year after a nearly snowless January,

it is supposed to be a tad colder

with temperatures struggling to get above freezing and the sun playing tag with scattered clouds. Call it a coin toss whether Willie will see his

shadow when he is yanked from his nap.

Part

of the spreading appeal of the

celebrations is because they are a welcome,

if silly, relief from the dreary

tedium of the depths of the

winter, long after the razzmatazz of

the Holidays have past when everyone

in cold climes are sick to death of snow, ice, howling winds, and leaden

skies. But a philosopher might speculate that

the surging popularity of Groundhog Days mirrors the growing anti-intellectualism of modern America and the spreading animus to science now officially embraced by a major political party and reflected in rejection of evolution, denial of climate change, anti-vaccine hokum, and a general

rejection of rationality. Or maybe that would be reading too much into a harmless custom.

So

how did all of this come to pass? Some claim religious roots stretching back to Neolithic Europe. The growing neo-pagan movement is explicit in

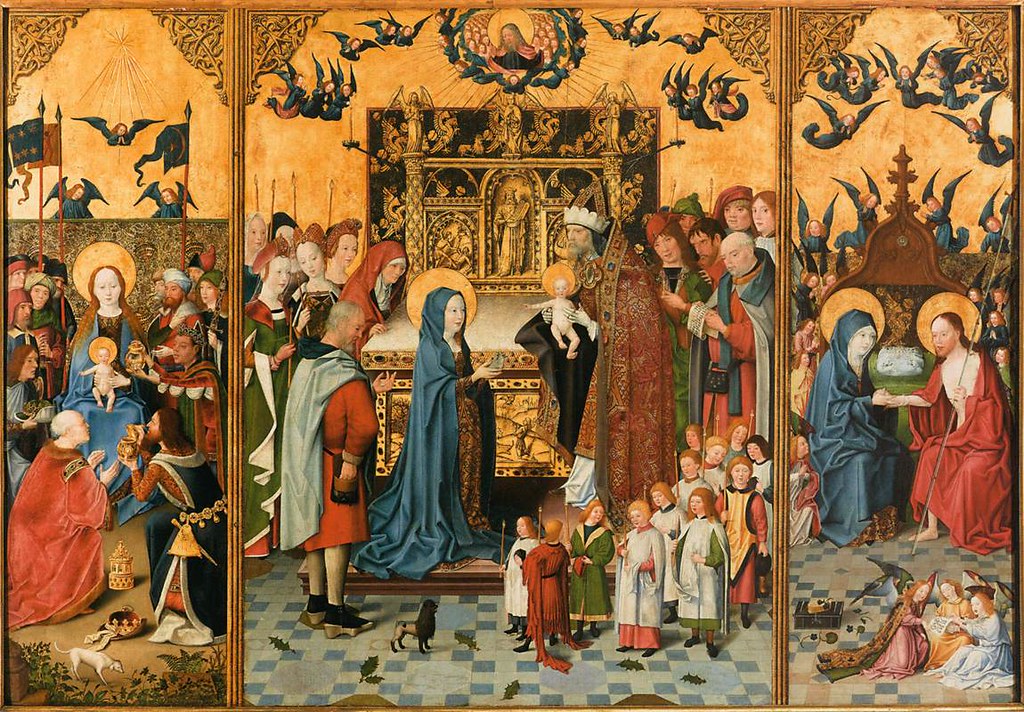

laying claim to it, but Catholics have their own customs which may, or may not have been cribbed from older traditions.

Groundhog

Day has been traced to pre-Christian

Northern European folk traditions stretching back in the mists of time. It is

notoriously difficult to pin down

precise origins of such oral

traditions or to know the complete

religious significance of them.

Tales about a beast—usually envisioned as a bear or

a badger that had powers to predict or control the

weather seem to have originated in Norse and/or Germanic tribal

societies and spread by diffusion or

osmosis to other European peoples

including the Slavs to the east and

the Celts to the south and

west. The celebration of the animal was

tied to the half-way point between Winter Solstice—Yule—and the Spring Equinox.

Although

most of the animal and weather lore that leads directly to Groundhog Day are of

Northern European origins, modern Wiccans

and neo-pagans have identified

it with the Celtic festival of Imbolc

one of the four seasonal quarter

festivals along with Beltane (Spring/Easter), Lughnasadh (Mid-Summer) and

Samhain (Fall/Halloween) that fall between the solstices and equinoxes. Traditionally it was a festival marking the first glimmers of spring while still in the grip of the cold and dark of

winter. As such it was distantly related to transition predicted by the Norse totem animal, but had no known

direct corresponding myth.

Instead

it celebrated the goddess Brigid patroness of poetry, healing, smith crafts, midwifery, and all arts of hand. In some stories

her feast on February 1 celebrated

her recovery after giving birth to the God—the Green Man—who will come into

his own and rule from Lughnasadh to

winter.

|

| Wiccans and other neo-pagans identify Groundhog day with the Celtic seasonal celebration of Imbolic and the goddess Brigid. |

In

Ireland with the coming of Christianity the Goddess and her

festival became identified with St.

Brigid of Kildare, along with Patrick

and Brendon one of the three Patron Saints of the country. Now thought to be apocryphal, St. Brigid in lore

was first recorded in the 7th Century and

expanded upon by later monks and scribes.

She was described as the daughter

of a Pict slave woman converted by

Patrick himself. Born in 451 in Faughart,

County Louth she became a holy woman, nun, and abbess who

founded a monastery on the site of an ancient temple to the Goddess Brigid in Kildare. She assumed

many of the pagan goddess’s attributes and

performed many miracles. Stories about the

Goddess and the Nun are so intertwined

that it is impossible to figure out

if the holy woman was real or an invention

of the Church intended to comfort

converts with familiar and beloved tradition.

Today

the best known tradition associated with the Feast of St. Brigid is the making of the off-center straw crosses from last

season’s straw that are hung as talismans

in Irish homes through Lent until

Easter.

Almost

all of the original traditions associated with the Goddess Brigid and Imbolc

had been eradicated or simply faded away by the 18th Century even in Gaelic

speaking regions. In the 20th

Century Wiccans and other neo-pagans have attempted to revive the old Celtic

traditions and in the process invented

rituals and lore to fill in the

lost gaps. Many believe the Quarter

Festivals and old Gods and Goddesses are accessible

spiritual metaphors for worship

of the natural world and the timeless rhythm of the seasons.

|

| Which came first? The straw Cross of St. Brigid has been interpreted as representative of the quarter festival and cardinal directions by Wiccans. |

That

included borrowing from St. Brigid, as well.

Her straw crosses are now described as not Christian at all but as ancient

symbols representing the Four

Quarter Festivals and the Four Cardinal

Directions. There is no way to prove or disprove that assertion.

The Rev.

Catharine Clarenbach, a Unitarian Universalist minister explained how modern practitioners view Imbolc in an entry

on Nature’s

Path, a U.U. pagan experience and

earth centered blog hosted by the

religious site Patheos. She called it

“a light not heat holiday” in which the slowly

lengthening days and first tenuous

hints at Spring-to-come give

hope to those trudging through the hard days. “When people are desperately ill, hope can fuel the long slog toward wholeness and healing,

even if that healing is not a cure.”

That

certainly ennobles the day beyond

the giddy fantasy of groundhog magic.

But

our trail to modern Groundhog Day does not end with the re-invention of

Imbolc. Indeed other than sharing a

date, the two celebrations have little in common.

Over

in England and Scotland a different Christian

tradition evolved—Candlemas observed

on February 1, the eve of St.

Brigid’s Day and often confused as British

equivalent. But Candlemas has very

early 4th Century Christmas roots as The

Feast of the Presentation celebrated by early Church patriarchs including Methodius

of Patara, Cyril of Jerusalem, Gregory the Theologian, Amphilochius of Iconium, Gregory of Nyssa, and John Chrysostom. It celebrated the presentation of Jesus

at the Temple in Jerusalem as an infant.

The celebration slowly spread from the Levant to the rest of the Church and Roman Empire. When the date of Christmas was finally fixed on December 25, the Feast of the

Presentation was added to the liturgical calendar forty days later on February 2.

That date by happenstance nearly coincided

with the old Roman festival Lupercalia

which simultaneously celebrated the

Roman version of the Greek God Pan who was sacred to shepherds

in the Spring lambing festival and Lupa the she-wolf who

suckled Romulus and Remus, legendary twin founders of

Rome. In evolving Roman practice it had

become a major popular holiday in Rome itself and associated with the revelry

and abandon of other feasts.

Lupercalia was outlawed by the ascendant Christians but still widely,

if covertly, celebrated by ordinary Romans.

The official Feast of the Presentation, coming just before Lent was

hoped to ease acceptance of Church teachings.

Pope Gelasius I began calling

this festival, which set off the carnival

season, the Feast of the Candles,

later known as Chandelours in parts

of France, the Alps, and the Pyrenees

and as Candlemas in Britain. It

connections to Lupercalia have caused

some modern neo-pagans to view that celebration as a Latin equivalent of the German and Norse totem animal observations. That is highly

speculative and tenuous at best.

But

in Scotland we do find Candlemas as the first indication that the Northern

European custom had been introduced to Britain.

An early Scots Gaelic proverb went:

The serpent will

come from the hole

On the brown Day of Bríde,

Though there should be three feet of snow

On the flat surface of the ground.

On the brown Day of Bríde,

Though there should be three feet of snow

On the flat surface of the ground.

Although

it was a serpent, not a bear, that was mentioned, the emergence of a totem

animal to herald Spring was clearly there.

Over time looking for badgers stretching their legs at Candlemas became

a folk tradition in rural areas of Scotland and England.

Without

mention of an animal witness this early English verse asserts

If Candlemas be

fair and bright,

Winter has another flight.

If Candlemas brings clouds and rain,

Winter will not come again.

Winter has another flight.

If Candlemas brings clouds and rain,

Winter will not come again.

But

that custom was never wide spread and did not seem to have traveled to the New World with early settlers from the colonies.

It

took German peasants lured to frontier areas of Pennsylvania in the

late 1700s to do that. The use of groundhogs for prognostication rather than bears or badgers—both of which were far

more dangerous and hard to manage than the lumbering and common local rodents—was well established when the first recorded note of the celebration was

made in English in an 1841 diary entry by Morgantown shopkeeper James Morris:

Last Tuesday, the

2nd, was Candlemas day, the day on which, according to the Germans, the

Groundhog peeps out of his winter quarters and if he sees his shadow he pops

back for another six weeks nap, but if the day be cloudy he remains out, as the

weather is to be moderate.

All

across central and western Pennsylvania where Germans had settled in large

numbers local Groundhog lodges sprang up in many towns to

celebrate the annual appearance of the weather predicting critters. An elaborate

communal meal called a Fersommling featuring groaning tables, orations, skits,

and music led up to a ritual presentation of the local

groundhog. These lodges and festival

gatherings were also an important tools to preserve German cultural

identity in communities pressed hard by Englanders—native English

speakers. Only the Pennsylvania

Dutch dialect was allowed to be spoken at 19th Century Fersommlings with

fines levied for each English word uttered.

|

| An early Groundhog Day cartoon. |

In 1887 in a burst of civic boosterism Colby

Camps, editor of the Punxsutawney

Spirit promoted his home

town as the official Groundhog Day

home and the local beast, always named Phil

generation after generation regardless

of gender, as the town’s official meteorologist. The first story rapidly got picked up by

other local and national publications which

eagerly reported the result of Phil’s observation. It became an annual tradition and publicity

for the event and town grew year after year.

By the 1920 towns from the East Texas Hill Country and North

Carolina, many with their own German immigrant populations, to Ontario and French speaking Quebec were hosting

their own celebrations.

Then, as noted, the 1993 movie inspired still more.

Today the accuracy

of the various groundhogs is in dispute.

Backers, including the local Groundhog society boast accuracy rates of between 80 and 90%. Cold

hard statistical analysis refutes that unsubstantiated

claim.

A study of several Canadian towns with Groundhog celebrations dating

back 30 to 40 years found only 37% rate of accuracy. The record at Punxsutawney dating all the

way back to that first 1887 outing is hardly better—only 38%. Both are much worse than random 50/50 odds.

No comments:

Post a Comment