|

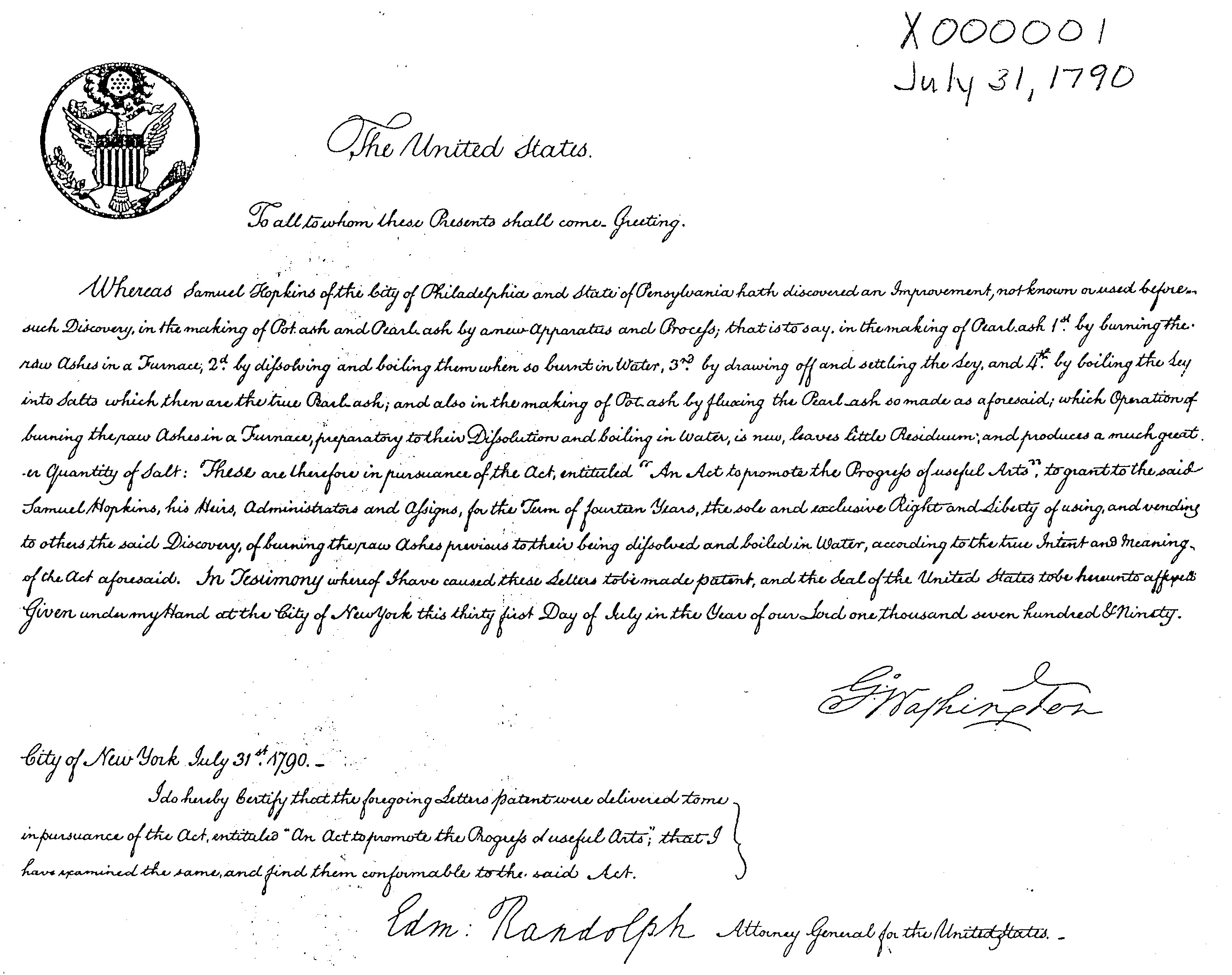

| Samuel Hopkin's patent with the original signatures. The date and number in the top right of the page were addeda after the Patent Act of 1836. |

On

July 31, 1790 President George

Washington affixed his signature to

a document granting the First United States Patent. It was the culmination of a process that began when Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, himself an inventor with more than a passing interest in innovation carefully reviewed the

application. When he concluded that the submission was both original and useful he signed the document and passed it on to Secretary of War Henry Knox who also

approved it and then sent it to Attorney

General Edmund Randolph. Only when

he was finished with it did it land on Washington’s desk.

It

was a cumbersome procedure entailing

most of the Executive Branch of the

still new Federal Government. It was an improvisation by Jefferson who for some reason left out his rival for Washington’s favor, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander

Hamilton despite the New Yorker’s

avowed interest in encouraging

American industry. Chances are very good that the snub was not accidental.

Jefferson

had to ad lib a review process

because when Congress authorized the

government to issue patents it neglected to say how it should be done. The act simply authorized the government to carry out the powers described in Article 1. Section 8 of the Constitution:

Congress

shall have the power...to promote the progress of science and useful arts by

securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to

their respective writings and discoveries.

The first person

to take advantage of the new law was Samuel Hopkins, a Philadelphia inventor

who petitioned for a

patent on an improvement “in the making of Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new

Apparatus and Process.” As inventions go, it was pretty mundane, but potash, which was

derived from the ash residue of vegetable matter, usually wood, and was

used in the making of soap

and candles. Both of those necessities had usually been made at home in the Colonial Era. Hopkins

hoped his process would encourage their manufacture in small scale craft shops for local sale. So it perfectly fit Jefferson’s

key criterion—usefulness.

|

| Samuel Hopkins was granted the first Patent for his new process of making potash. |

Hopkins was so excited

about the prospects for his process that the very

next year he was granted the first patent from the Parliament of Lower Canada in 1791,

and issued by the Governor

General in Council Angus MacDonnel at Quebec City.

The approval process was repeated two more times that year for a

new candle-making

process and Oliver Evans’s flour-milling machinery.

The following year the trickle of applications

became a rushing steam as innovative and ambitious dreamers

submitted their ideas for a $4 fee—a cost that although not insignificant could be raised by most. Whatever

his own interest in examining

the models and drawings, the work load was overwhelming

the Cabinet and the

President’s attention.

Jefferson substantially streamlined the process. He handed

over initial review to a

State Department Clerk who

would make a recommendation

which he would approve and send on to the President

for a final signature. In practice the

final two steps began to simply rubber stamp the Clerk’s determination.

This process continued into Jefferson’s own Presidency. At his urging Congress created Patent Office with its

own staff of clerks. More than

10,000 patents were issued before 1836 when I fire destroyed all of the records. That fire

spurred Congress

to enact the Patent Act

of 1836 which authorized the hiring of professional patent examiners in

addition to the clerks. It also

authorized new patent documents to be issued in all cases where the patent

could be confirmed by other records such as copies held by the recipient. 2,845 patents were restored and issued a number beginning with an X. That

included Hopkins’ first patent. The rest

of the missing patents were voided.

To

date there are more than five million patents that have been issued to

Americans and other nationals by the U.S. Patent system. Since 1975 patents have been granted by the United States Patent and Trademark Office, a

part of the Department of Commerce.

By

the way a copy of Hopkins’ patent with the original signatures still exists and

is held by the Chicago Historical

Society.

No comments:

Post a Comment