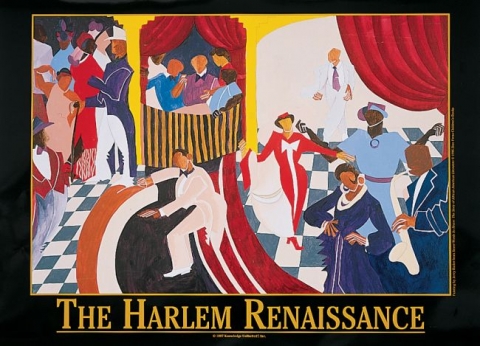

From time to time there are magical, fertile places—communities

that for one reason or another fairly burst

with new energy and creativity producing artists of all sorts, each seeming to

gain strength and speed by the success

of their neighbors and associates. Boston/Cambridge/Concord

in the 1840s and ‘50s was one. Expatriate Paris between the Wars was surely another.

New

York City’s Harlem from the years around World War I until the Depression all but wiped out a vigorous Black

middle class was such a place and time.

By the mid-19th Century the old Dutch

village on northern Manhattan had

been developed as an upper class suburb of the City with mansions lining spacious boulevards. By the turn of the 20th Century the gentlefolk

had fled the encroaching tenement neighborhoods of European immigrants. In 1910 an entire large block along 135th

Street and Fifth Avenue was purchased by a group of Black investors and a church.

It became the seed of a

rapidly growing Black community.

In its earliest years it was solidly

middle class attracting the cream of

an educated elite, professionals, business people, and skilled

workers. When World War I cut off the continuing supply of cheap labor from Europe and war

production created unheard of opportunities,

tens of thousands of Southern Blacks,

chaffing under the deteriorating

conditions of the Jim Crow Era, flooded

into the neighborhood, as did very culturally

distinct immigrants from the Caribbean.

Some trace the beginning to what

would be called the Harlem Renaissance to

the 1917 premier of Three Plays for a

Negro Theatre by poet Ridgely

Torrence. By 1919 poet Claude McKay was

boldly staking out a new militancy

in his sonnet If We Must Die. The

ideas of W.E.B. Du Bois in the

NAACP’s journal The Crisis and by Hubert Harrison’s Liberty League in The

Voice helped put a political and philosophic stamp on the community.

Marcus Garvey’s nationalist ideas

and the Black Churches all contributed.

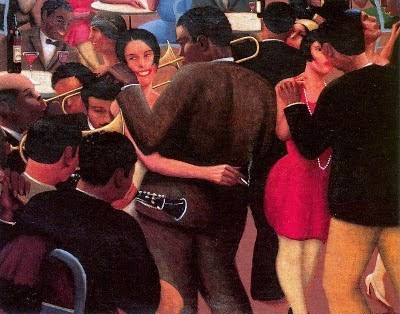

The Harlem Renaissance produced

artists of all types—novelists, playwrights, musicians, performers of

all types, painters, and sculptors. But above all, it produced poets. The most famous was Langston Hughes. But today I

want to feature some of the other voices

that still speak powerfully today.

Let’s start with Claude McKay, whose

defiant poem helped launch the era. Like

several other prominent figures, McKay was an immigrant from the Caribbean;

coming from his native Jamaica in

1912 to study at Booker T. Washington famed

Tuskegee Institute. He was

immediately repelled by the virulent

racism he encountered in the Deep South,

unlike anything he had encountered at home.

He also rebelled at Washington’s rigid

semi-military discipline and his willingness to be—or seem—subservient to the White

establishment. He moved on to study at Kansas State University where he

encountered Du Bois’s Souls of Black Folk. Like Du Boise McKay became a Marxist.

He abandoned his studies of agronomy

and after a short period as a railroad

dining car waiter, arrived in New York determined to pursue a literary career. In 1919 he joined Max Eastman’s The Liberator where

he quickly rose to be joint editor. The race

riots sweeping the country that

summer inspired his defiant, seminal

poem.

If We Must Die

If we must

die, let it not be like hogs

Hunted and penned in an inglorious spot,

While round us bark the mad and hungry dogs,

Making their mock at our accursèd lot.

If we must die, O let us nobly die,

So that our precious blood may not be shed

In vain; then even the monsters we defy

Shall be constrained to honor us though dead!

O kinsmen! we must meet the common foe!

Though far outnumbered let us show us brave,

And for their thousand blows deal one death-blow!

What though before us lies the open grave?

Like men we'll face the murderous, cowardly pack,

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

—Claude McKay

Countee

Cullen came from a very different

background than McKay, illustrating the wide diversity in the community. Orphaned

at 16 he was adopted into the home

of Harlem’s most important clergyman,

the Reverend Frederick A. Cullen, of

Salem Methodist Episcopal Church. He took the name of his foster father and

enjoyed being at the epicenter of

Harlem life. At the same time he was

sent to prestigious White schools

were he excelled as a scholar and was quickly recognized as a

poet. In 1923 he graduated from New York University and had been

accepted to graduate school at Harvard.

He had already published several poems in important magazines and was lauded by white critics as a voice for his race. That year he published The Ballad of a Black Girl,

the first important collection of

what would become known as the Harlem Renaissance. It was widely hailed in his own community as

well as praised by the literary establishment.

Cullen secured his place in Harlem when he married, to public

jubilation, Du Bois’s daughter,

uniting the two most influential families in the community.

Cullen believed that no authentic Black poetic voice had ever

been able to establish itself. He consciously modeled his work on the English Romantic of a hundred years

earlier, especially John Keats. He rejected modernism and literary trends like imagism and free verse. When his subsequent collections drifted

away from the depiction of Black life, he fell

out of favor with Black readers and ended his long career co-writing plays, including the musical St. Louis Woman which

made Pearl Bailey a star when it finally premiered on Broadway in 1947, months after Cullen’s death.

A Brown

Girl Dead

With two white roses on her breasts,

White candles at head and

feet,

Dark Madonna of the grave she rests;

Lord Death has found her sweet.

Her mother pawned her wedding ring

To lay her out in white;

She’d be so proud she’d dance and sing

To see herself tonight.

—Countee Cullen

James Weldon Johnson.

James Weldon Johnson has been called the elder statesman of the Harlem Renaissance. More than a generation older than the others, he was born in 1871 in Jacksonville, Florida. His mother encouraged him to study European literature and music. After graduating from Atlanta University, he returned to his home town as the principal of a segregated high school. He was also active in his church choir and began composing hymns. In 1900 he wrote Lift Every Voice and Sing which became famous as the “Negro National Anthem” after being widely performed by Fisk University’s legendary gospel chorus. The next year he joined his brother Rosamond in New York City to launch a successful joint career as a songwriting team for the theater. Based on this experience he published his novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, about a musician who turns his back on his racial roots and identity for success in the white world.

By 1920 he was an organizer for the NAACP and a leading figure in the Harlem community. Not only did he publish his own poetry, but he became a hugely influential editor and compiler of black verse for anthologies like The Book of American Negro Poetry in 1922. He continued to write, returning to themes of his rural southern roots, until he died in 1938. His work had helped revive interest in African-American folk traditions.

The Creation

And God stepped out on space,

And He looked around and said,

“I’m lonely—a

I’ll make me a world.

And far as the eye of God could see

Darkness covered everything,

Blacker than a hundred midnights

Down in a cypress swamp.

Then God smiled,

And the light broke,

And the darkness rolled up on one side,

And the light stood shining on the other,

And God said, “That’s good!”

Then God reached out and took the light in His

hands,

And God rolled the light around in His hands

Until He made the sun;

And He set that sun a-blazing in the heavens.

And the light that was left from making the sun

God gathered it up in a shining ball

And flung it against the darkness,

Spangling the night with the moon and stars.

Then down between

The darkness and the light

He hurled the world;

And God said, “That’s good!”

Then God himself stepped down --

And the sun was on His right hand,

And the moon was on His left;

The stars were clustered about His head,

And the earth was under His feet.

And God walked, and where He trod

His footsteps hollowed the valleys out

And bulged the mountains up.

Then He stopped and looked and saw

That the earth was hot and barren.

So God stepped over to the edge of the world

And He spat out the seven seas;

He batted His eyes, and the lightnings flashed;

He clapped His hands, and the thunders rolled;

And the waters above the earth came down,

The cooling waters came down.

Then the green grass sprouted,

And the little red flowers blossomed,

The pine tree pointed his finger to the sky,

And the oak spread out his arms,

The lakes cuddled down in the hollows of the ground,

And the rivers ran down to the sea;

And God smiled again,

And the rainbow appeared,

And curled itself around His shoulder.

Then God raised His arm and He waved His hand

Over the sea and over the land,

And He said, “Bring forth! Bring forth!”

And quicker than God could drop His hand.

Fishes and fowls

And beasts and birds

Swam the rivers and the seas,

Roamed the forests and the woods,

And split the air with their wings.

And God said, “That’s good!”

Then God walked around,

And God looked around

On all that He had made.

He looked at His sun,

And He looked at His moon,

And He looked at His little stars;

He looked on His world

With all its living things,

And God said, “I’m lonely still.”

Then God sat down

On the side of a hill where He could think;

By a deep, wide river He sat down;

With His head in His hands,

God thought and thought,

Till He thought, “I’ll make me a man!”

Up from the bed of the river

God scooped the clay;

And by the bank of the river

He kneeled Him down;

And there the great God Almighty

Who lit the sun and fixed it in the sky,

Who flung the stars to the most far corner of the night,

Who rounded the earth in the middle of His hand;

This Great God,

Like a mammy bending over her baby,

Kneeled down in the dust

Toiling over a lump of clay

Till He shaped it in His own image;

Then into it He blew the breath of life,

And man became a living soul.

Amen. Amen,

—James

Weldon Johnson

No comments:

Post a Comment