On this

morning four years ago out in Butte, the old Montana coper mining

town where a good slice of often violent labor history went down, Wobblies from

the Missoula General Membership Branch of the Industrial Workers of

the World and other folks will gathered at the grave of Frank Little in Mountain

View Cemetery and then caravanned to a picnic area near the Milwaukee

Bridge where the tough as nails union organizer was lynched exactly 100 before. They went out on the trestle where his

tortured body was left dangling and laid a wreath. My

old friend and Fellow Worker working class troubadour Mark

Ross who lived for a good many years in Butte returned to town for the

event to sing.

The story

of Little and his violent demise would make a hell of a great movie. That one has never been made is testimony

to the suppression and erasure of labor history from popular

culture. Instead his memory is

preserved as a Wobbly folk hero, enshrined alongside other martyrs

of the One Big Union like Joe Hill, the victims of the

Centralia Massacre, and Westly Everet who was lynched in his Doughboy

uniform.

In an

effort to change that Little great-grand niece Jane Little Botkin, has

written the now definitive book on her ancestor, Frank Little and the IWW: The

Blood that Stained an American Family.

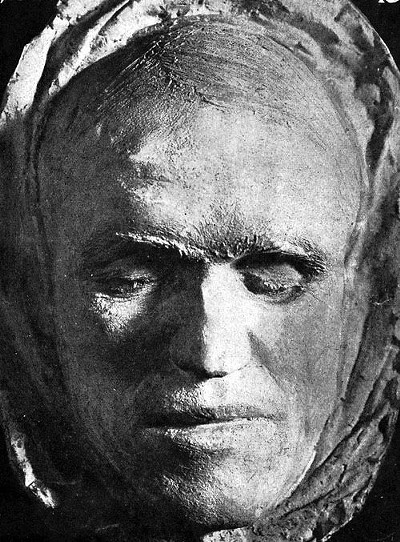

Jane Little Botkin's book about her great grand uncle details the last 13 days of Frank Little's life in Butte and his murder.

Little was born in 1879 in Indian Territory, modern Oklahoma.

By his account his father was white and his mother was a member of the Cherokee Nation. Other than that almost nothing was known

about his family life and education until Botkin’s research and book. Botkin disputes

the Native American lineage chalking it up as a good yarn.

Like many of the itinerant

young workers Little left family and much of his identity behind when he hit

the rails looking for work sometime in his teens.

Those from Texas and Oklahoma often did some cowboying and joined the huge

bands necessary to follow the wheat

harvest north across the plains all the way in to Canada. He might have headed

to the Pacific Northwest to lumberjack and harvest fruit, hit the docks

at San Pedro and other California ports, joined railroad construction gangs, and maybe

even washed dishes in a skid road eatery. Frank certainly was at home among these kinds of men, the dispossessed, mobile working class who

would make up the core of the IWW in the West.

Around the turn of the 20th Century, Little found himself

working in one of the most important

industries in the West—hard rock

metal mining. This was brutally hard labor and among the most dangerous work in world.

The mining industry had evolved from small owner operated

claims around boom towns to huge industrial scale operations often owned and operated by Eastern financial interests. Big

companies bought up—and sometimes

outright stole—small operations

and then gobbled up local and regional

operations creating near monopolies

in gold, silver, lead, and copper mines. The companies demanded 12 and 14 hour days of back breaking labor six days a week. Safety

of the miners was hardly a

consideration as workers could be replaced

by a “reserve army of the unemployed.” As in the coal industry, there were company

towns and pay in script that could only be redeemed for over-priced goods at a company store.

Conditions

fostered labor rebellion, at first largely spontaneous and unorganized. From the 1870’s onward in the territories and states of the west barely

beyond the frontier era where civil law was absent or purchased outright by mine owners, brutal, violent strikes were the hallmark of the industry.

By the 1890’s The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) were lending militant

leadership and organization to

the class war in the mines. Little joined

sometime around 1900 and was soon a rising

organizer in the field.

In 1905 the WFM became the largest founding organization of the radical new IWW, which aimed to bring the muscular industrial unionism of the miners to all industries. Steeped in the open warfare of the West, the

WFM brought a particularly pugnacious

variety of bare knuckle direct action to an organization also founded by parlor intellectuals like Daniel DeLeon of the Socialist Labor Party (SLP), mainline Socialists like Eugene V.

Debs, and “home guard”

industrial unionists from the East.

The WFM’s Charles Sherman was installed

as the first—and only—President

of the IWW. But his high handed top-down exercise of executive authority was at

odds with the already growing

culture of shop-floor democracy of the union and he clashed with DeLeon and

other intellectuals in the movement.

After a year, Sherman was gone

and the WFM disaffiliated from the

new union.

But many WFM leaders and a lot of the rank

and file, including William D. “Big

Bill” Haywood and Vincent St. John, stuck

by the IWW. With Heywood on trial for the bombing murder of

former Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg,

St. John took on the job of General

Secretary-Treasurer of the union.

Heywood followed after he was cleared

in the famous trial in which he was defended by Clarence Darrow.

Little was proud to transfer his loyalties to the new revolutionary union. For the next several years he seemed to be everywhere across the West

in the thick of IWW strikes and battles

in a number of industries. In

addition to his continued work with miners, he organized lumber workers in the Northwest, oil field workers

in the boom towns of Texas and his

native Oklahoma, and California fruit

pickers. He was noted for his fearlessness.

He was part of the Free Speech Campaigns in Missoula, Fresno, and Spokane. The IWW relied on street corner orators like Little to reach migrant workers in the skid roads of towns. From these areas of shoddy rooming houses, hotels, bars, and whore houses, bosses recruited workers for the lumber camps, mines and harvests. In order to enforce strikes on those jobs, the IWW had to organize the transient workers who would otherwise become a pool of scabs. Town after town attempted to shut down the street corner meetings by arresting speakers. The IWW developed a tactic by which they would send out a call for “footloose Wobblies” to flock to the towns and overflow the jails by mounting their soapboxes one after another. These successful free speech fights worked because eventually towns went near bankrupt feeding and housing the hundreds of defiant IWW members that they rounded up.

Little either helped organize the campaigns, or blew into town to take his place in the

disobedience. In Spokane he was sentenced to 30 days in jail for reading

the Declaration of Independence.

Little was widely respected by the rank and file for his sheer fearlessness. In 1915

in the company of James P. Cannon, much later the founder

of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers

Party, Little came to Duluth,

Minnesota, the Iron Range port,

in support of strike of ore-dock workers

against the Great Northern Railway. Little was kidnapped by company “detectives” and held prisoner in a remote cabin outside of town. Rank and file members got wind of where he was being held and staged a daring rescue mission.

In 1916, Little was elected to the IWW General Executive Board. The Board was already embroiled in controversy over how to respond to the increasingly likely event of American intervention in World War I. Little was elected as a radical among radicals, backing open and fervent opposition to the war and a possible draft as the only possible response for an organization dedicated to solidarity of the world-wide working class.

Ralph

Chaplin, cartoonist, illustrator,

pamphleteer, and author of the labor hymn Solidarity

Forever became editor of Solidarity,

the IWW English language newspaper

in the East in 1917. He led a board faction that argued against any

overt anti-war agitation by the IWW for fear that it would excuse the unleashing of a massive government

repression, “un-like anything we

have ever seen.” The majority of the

Board led by Haywood—radicals but also practical

union men—were against general

opposition but supported

continued action in “essential war

industries” even if strikes would disrupt war production. Little was in the small minority who demanded

opposition to the war on principle.

“Better to go out in a blaze of glory than to give in,” he said. “Either we’re for this capitalist slaughterfest or we’re

against it. I’m ready to face a firing

squad rather than compromise!”

After war was declared in April of 1917, Little headed back out to the field where “essential war production” was exactly the target of a major campaign

in the copper industry that

year. There was hardly any more critical

industry in that year than copper, which was essential in the manufacture of brass for millions of rifle and machine gun cartridges, and artillery shells. It was also needed for the miles of telephone wire that would be strung along the front, electrical wiring, and automobile parts for an increasingly mechanized Army.

Little arrived in Bisbee, Arizona where IWW organized Metal Mine Workers Union No. 800. Union presented a list of demands, most of them safely related, to the management of the largest mining company in the area, Phelps Dodge. Despite his personal militancy, Little discouraged calling an immediate strike because the union had not laid enough

ground work. But when the rank-and-file voted to go out against the company on

June 29, Little stood by them. He soap

boxed and helped bring out the

largely unorganized workers at two other large operations idling 3,000 miners and shutting down 80% of local production.

In his speeches, Little was not shy about asserting his opposition to

the war. When accused of being a German agent, he told Arizona Governor Thomas Edward Campbell, “I don’t give a damn what country your

country is fighting, I am fighting for

the solidarity of labor.”

Frank Little just missed the Bisbee Deportation. He was on his way to Butte for another confrontation with the copper bosses.

On July 12 an army of over 2000 “special deputies” swarmed across Bisbee and

near-by towns rounding up all know IWW

members and strikers. Little had

been called out of town on other union

business just before and missed

being one of 1,300 men were held at

the point of machine guns and loaded

into cattle cars. Over a day and a

half in blistering heat and with virtually no food or water they were hauled more than 200 miles away to tiny

Hermanas, New Mexico where they were

dumped and told they would be shot on sight if they returned to Bisbee.

Undeterred by what became known as

the infamous Bisbee Deportation, Little wasted no time making his way to Butte where a resurgent IWW was aiding a strike against Anaconda Copper, operator of the world’s largest open pit mine. Once again he fearlessly tied the

worker’s cause to the broader war. His fiery rhetoric included calling American Doughboys preparing to go the France

as, “scabs in uniform.”

Predictably the local press, controlled by Anaconda, had a field day accusing Little and the IWW of being German agents. They openly

called for vigilante “justice”

against the “traitors.”

Meanwhile the town of Butte was infiltrated by Pinkerton Detectives charged with silencing the leaders and crushing

the strike. One of those agents was Dashiell Hammett who became so disgusted by the work that he became

a lifelong radical. He became the pre-eminent writer of hard

boiled detective fiction. His character, the nameless Continental Op, was based on his Pinkerton experience and

his first novel Red Harvest was based on his Butte experience.

In the early hours of August 1,

Little was seized in his rooming house

bed by six masked men. The beat

him, tied him behind an automobile

and dragged him out of town to railroad bridge. There he was beaten again, and by some accounts castrated, before

being hung from the trestle. A note was pinned on him written in red crayon reading, “Others Take Notice. First and Last Warning,” and including the initials of several other IWW men

and strike leaders. The note was signed 3-7-77, the code used

by the Virginia City Vigilance Committee

more than four decades earlier.

The event was staged to look like it was the spontaneous act of outraged citizens

acting in a time honored Western

tradition. Local police made no attempt to locate or identify the masked men and

no charges were ever brought. There is, however, considerable circumstantial evidence that the lynching was the well-planned work of the Pinkertons at

the bidding of the Copper barons and

that the motive was not patriotism

but as Big Bill Haywood said, “…because there is a strike in Butte, and he was

helping to win it.”

It turned out that Ralph Chaplin’s predictions were to come

true. After Little’s murder Montana declared martial law in Butte. Union

leaders and “traitors” were rounded up and arrested. Both the strike

and the IWW local were smashed.

And that was just the harbinger of sweeping action against

the IWW and its leadership across the

country. Halls were raided, including the IWW General Headquarters in Chicago,

which was ransacked. IWW newspapers

and pamphlets were banned from the mails.

Foreign born members were seized

and deported under the infamous Alien Acts, the legacy of John Adams’s long past crusade against his Jeffersonian Republican enemies.

After the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia,

which IWW leaders like Heywood openly

admired, a Red Scare carried the

repression on even after the war. In

1919 101 IWW leaders were arrested and

charged with sedition in Chicago

and another 40 at Leavenworth, Kansas. That included virtually the entire leadership of the union including Haywood and

Chaplain. Heywood would notoriously skip bond and go to the Soviet Union to avoid trial, for which old

time Wobblies never forgave him.

Chaplain, who had foreseen it all,

was among those who spent years behind

bars.

No comments:

Post a Comment