Way back when dirt was new and I was an exceptionally earnest high school student, we learned that before there was William Shakespeare there was Geoffrey Chaucer, period. In those distant days students were generally assigned at least a chunk of The Canterbury Tales to read and try and decipher. We were told it was English, but it was Greek to most of us. I remember that after some hours of labor, I got a hazy idea of what he was writing about.

English literature prior to the 20th Century apart from a medicinal dose of the Bard, a dollop of Dickens, and a few lines from a dreamy Romantic poet has long been banished from most high school curricula. You might not even encounter Chaucer today in many introductory survey level English Lit. courses in College. Certainly, you would have to be an English major and toiling in the 200-300 level courses before you really encounter him.

Perhaps things are better for

Geoffrey in England. One hopes so.

An English inn similar to the one Chaucer wrote about in The Canterbury Tales and the Inne of the Shrews in Greenwich where he died.

I bring this up because October 25 mark the anniversary of Chaucer’s passing in 1400. He was then the resident of the Inne of the Shrews in Greenwich. After a lifetime as a mostly successful courtier, he had been out of favor and broke, but was recently restored to Royal favor. But he may have been murdered by those who did not take kindly to his portrayal of the clergy, or so some stories have it. None-the-less, he was respectable enough to be buried in an unimportant corner of Westminster Abby. In later years other literary men asked to be interred near him in what eventually became the revered Poet’s Corner.

Chaucer's crypt in Westminster Abby was located in a dim, obscure corner of the church but became the nucleolus of the celebrated Poets' Corner, the final resting place of the British literary elite.Today his fans celebrate his life on his death day because no one knows exactly when he was born. It was about 1342 or ’43 in London. He came from a Norman family whose name originally meant shoemaker. But the family fortunes had risen. His father was a successful wine merchant and minor courtier—deputy to the King’s Butler. Nothing is known of his education except that it was quite good. By the time young Geoffrey was ready to enter the service of the noble and highborn himself at about age 13 he could already read and write Latin, French, and Italian.

That career started with an appointment to the household of Elizabeth, Countess of Ulster and Prince Lionel in 1357. Two years later he was a soldier in France fighting for King Edward III in the 100 Years War. He was evidently a good and valuable soldier because after being captured by the French he was paroled under the terms of the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360. The King himself and other courtiers contributed to raising the substantial ransom of £16. It was during his presumably not too-uncomfortable imprisonment that Chaucer completed, according to some sources his first literary work, Romaunt of the Rose, a translation from the French into the Anglo-Norman language of the court.

Around 1337 Chaucer apparently married very well indeed. His wife, or at least the mother of his two sons, was Philippa Roe, the sister of the future wife of John of Gaunt, third surviving son of Edward III. Due to this happy circumstance, he enjoyed the support and patronage of the Prince as long as he lived.

In 1369 he would re-work that earlier Romaunt of the Rose into vernacular English, what we now know as Middle English in The Book of the Duchess, dedicated to his sister-in-law after her death.

Such connection earned him more important and lucrative appointments. From 1338-78 he traveled extensively in Europe on several diplomatic and commercial assignments. He was said to have met the Italian Poet Petrarch on one such trip. He was also exposed to Dante’s Divine Comedy, which was written in vernacular Italian rather than Latin. This was supposedly an inspiration for Chaucer to work in vernacular English but as we have seen, he was already working in that language.

Back in England he was awarded the

very lucrative post of Comptroller of

the Customs and Subside of Wools, Skins, and Tanned Hides for

the Port of London, just the kind of

position where money could not help but fill

the purse of a poor, but honest public

servant. He survived a charge of rape by Cecile Champaigne and was able to get

her to withdraw her suit after a hefty private

settlement.

Chaucer's fortunes waxed and waned with those of his patron, John of Gaunt the Earl of Lancaster.

He could survive scandal, but not the shifting sands of politics. With John of Gaunt out of favor, so was he. He lost his post and free housing. But he moved to Kent, got a minor sinecure as Postmaster, and eventually was elected to Parliament. Away from London and the demands of court Chaucer devoted himself more and more to literature. He composed Troilus and Criseyde, a long poem based on a Trojan romance by the Italian poet Boccaccio.

When his wife died and with John out of favor, Chaucer was sued for debt. Several friends and acquaintances were executed. But in 1389 John returned to power and influence over his nephew Richard II, who in turn favored the poet with a new appointment as Clerk of the King’s Works responsible for the upkeep and repair governmental buildings in and around London. He was the beneficiary of Royal gifts and pensions in the 1390’s.

It was during this period that he

did most of his work on his magnum opus, The

Canterbury Tales. The loose

collection was said to have been inspired in some ways by Dante’s journeys

through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. But Chaucer’s tales were grounded in the real, even mundane

world.

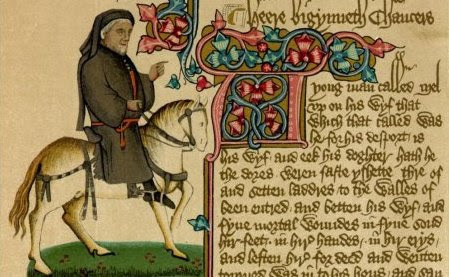

From an illuminated manuscript of the tales. The figure on horse back is thought to be Chaucer himself.

A group of 30 pilgrims gather for a journey to the grave and shrine of Thomas à Becket in an Inn much like the one in which Chaucer himself resided. It was a remarkably diverse group cutting across the rigid class lines of England at the time. Included in the group and telling their stories at the behest of the inn keeper were a knight, a monk, a prioress, a plowman, a miller, a merchant, a clerk, and an oft-widowed wife from Bath. The stories, some of them borrowed from earlier tales and sources, were often humorous and sometimes bawdy.

Chaucer never lived to complete the work. Perhaps because he was interrupted by another episode of political intrigue.

After Chaucer’s patron John died, Richard II disinherited his son, Henry of Bolingbrook. Henry returned from exile in France in 1399 to supposedly re-claim his lands and titles. He quickly gathered a large army against the king. He deposed Richard and seized the crown. Chaucer was reportedly in Henry’s service at the time, ever loyal to the line of John of Gaunt. As Henry IV the new king rewarded such loyal service with a generous increase in his annuity.

But he never received either lands or title and remained until he died the next year, as he had lived, a commoner with uncommon connections to Royalty.

For those who may have forgotten—and

for those who have never seen it, here is a sample of Chaucer’s most famous

work:

Here begins the Book of the Tales of Canterbury

Whan

that aprill with his shoures soote

The

droghte of march hath perced to the roote,

And

bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of

which vertu engendred is the flour;

Whan

zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired

hath in every holt and heeth

Tendre

croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath

in the ram his halve cours yronne,

And

smale foweles maken melodye,

That

slepen al the nyght with open ye

(so

priketh hem nature in hir corages);

Thanne

longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And

palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To

ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;

And

specially from every shires ende

Of

engelond to caunterbury they wende,

The

hooly blisful martir for to seke,

That

hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

Bifil

that in that seson on a day,

In

southwerk at the tabard as I lay

Redy

to wenden on my pilgrymage

To

caunterbury with ful devout corage,

At

nyght was come into that hostelrye

Wel

nyne and twenty in a compaignye,

Of

sondry folk, by aventure yfalle

In

felaweshipe, and pilgrimes were they alle,

That

toward caunterbury wolden ryde.

The

chambres and the stables weren wyde,

And

wel we weren esed atte beste.

And shortly, whan the sonne was to reste,

So

hadde I spoken with hem everichon

That I was of hir felaweshipe anon,

And

made forward erly for to ryse,

To

take oure wey ther as I yow devyse.

But

nathelees, whil I have tyme and space,

Er that I ferther in this tale pace,

Me

thynketh it acordaunt to resoun

To

telle yow al the condicioun

Of

ech of hem, so as it semed me,

And

whiche they weren, and of what degree,

And

eek in what array that they were inne;

And

at a knyght than wol I first bigynne.

—Geoffrey Chaucer

No comments:

Post a Comment