According to historians of American sports the first official college football season got

underway on November 6, 1869 when teams from Rutgers College, now Rutgers

University, and the College of New

Jersey, now Princeton University,

got together on the Rutgers campus for a rough and tumble game of football which was sanctioned

and approved by both colleges. It

was a short season. The next game was

played by the same teams at Princeton one week later. Season over.

Just two teams and two games.

The Queensmen of Rutgers won the first game by a score of 6-4 but the

New Jersey Tigers came back in the re-match

to win 8-0. The anal retentive record

keepers of intercollegiate sports are

torn on who to retroactively declare the

first unofficial national Champion since

a third and possibly decisive game was never played as originally intended,

probably because the two teams could not agree under what rules to

conduct the contest. Princeton was named

the champion by the Billingsley Report and the National

Championship Foundation, but respected college football research historian Parke H. Davis named the two teams co-champions.

But for the players—there were no coaches yet—the split season had to be

a lot like kissing your sister,

pleasant enough but not thrilling.

To say that an intercollegiate sport

of any kind was in its infancy is hardly an exaggeration. Only rowing

was widely contested and had been since Harvard and Yale first

went at it in 1852. A few colleges were

playing a form of the new bat and ball

game called baseball beginning

with Amherst vs. Williams Colleges in 1859 and that was pretty much it.

Students had been playing rough kick ball goal games on a casual pick-up team basis on several campuses

for at least twenty years, maybe longer.

There were few, if any rules, no set number of players on a

team—anyone could jump in the game—and no set field dimensions. Students let off steam and tended to emerge

with black eyes, broken

teeth, fractured bones, and a deep abiding thirst quenchable only with quantities of beer or rum punch. College administrators took a dim view

of it but considered the games preferable to another popular college pastime—rioting. By the post-Civil War era football clubs were formed on some campuses and

informal—actually illegal—matches

between unofficial teams sometimes occurred.

Heavy betting by players, students, and faculty rode on some of

these clandestine games.

The colleges of Rutgers and New

Jersey finally decided it was best to sanction the competition to control the violence

and debauchery that the unofficial matches had encouraged. Still the serious academics were unsure and

dubious about games and frivolity in general which ran against the

entrenched Puritanism that prevailed

among most of the faculties.

Arranging the official matches was

not easy because each team played by different rules which had evolved

independently over time. Finally, it

was determined to play each game by the home team’s rules—which turned out to

be a decisive advantage in each game.

The decision of what rules to use in a final third game was put

off. In the end neither team would agree

to an advantage to the other and the third game had to be called off.

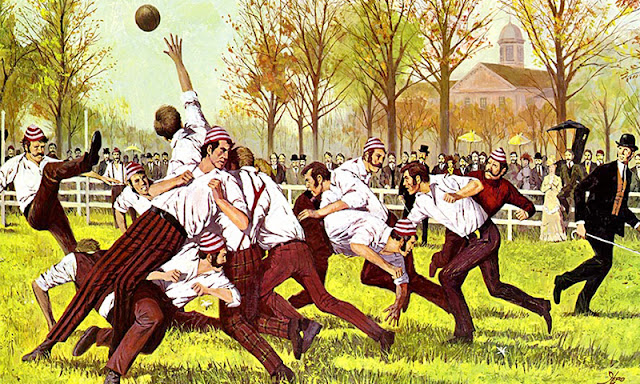

Modern Americans would hardly recognize

the game that was played on November 6 as Football. It more closely resembled a crude version

of what we now call soccer with some

elements of Rugby, our form of the

game’s most immediate ancestor.

The ball was round. Players wore neither helmets nor identifying uniforms

and ran in slick, leather soled street

shoes or boots. Twenty-five men on

each side played both offense and defense. There were no time outs, even for injuries

and wounded players had to be dragged off the field by spectators

dodging the action. There also were no substitutions

so knocking an opponent unconscious or breaking a leg was advantageous. Players were forbidden to pick up and

run with the ball. The ball was advanced

by kicking. The field was 125

yards long and 75 yards wide, and unmarked. Under the circumstances the

game could only be bloody and brutal.

Rutgers had the advantage of both

using its own rules and of some speedier runners who could occasionally break

out of the mob scene and advance the ball. Thus, they won the first game.

At New Jersey the rules allowed a

player to catch the ball with his hands on the fly and execute a free kick which could send the ball

high over player’s heads and well down field.

This erased Rutgers’ advantage and allowed the Tigers to blank their rivals. Rutgers was outraged by the “unfair tactics”

but there was nothing they could do about it.

Interest at both colleges in the

games was so high that during the short “season” students could hardly

concentrate of their studies, so wrapped up in the games were they. Faculty members pontificated about the moral

collapse of a generation and wrung their hands over the

distractions—setting up another time honored tradition.

Over the next decades America went sports

crazy. Baseball erupted seemingly overnight into the National Pastime.

Boxing was closely followed from men’s club smokers to ballyhooed

World Championships in multiple weight divisions covered in detail

in illustrated magazines like the

Police Gazette. Thoroughbred racing and

county fair pacers and trotters attracted racetrack crowds and fueled a burgeoning bookmaking industry. College

football would be swept up in the general rise.

Sports

writers for major newspapers began to cover

the games and clamor for standardization

of the rules. Reformers demanded rule

changes that made the games less of a blood

bath. On different campuses rules

evolved differently. It was not until

June 4, 1875 that a form of the game recognizable to us—running with an oval ball, 11-man sides, and tackling

to end a play would be contested

between Harvard and Tufts Universities. The next year Yale player Walter Camp drew up standardized

rules based on the Rugby game being

played by McGill University in Toronto. Harvard, Columbia, and the College of New Jersey—formed the Intercollegiate Football Association,

the first league. Yale joined three years later in 1879. The rest, as they say, is history.

On the 50th anniversary of the first game Rutgers honored the surviving members of the 1869 team.

Rutgers has always

been particularly proud to have hosted the first college football

game. In fact, their boasting

about it has kept their claim alive. In

1919, the fiftieth anniversary of the game the University honored all

the surviving members of the team at their Homecoming celebration. Members continued to attend until the last

one, George H. Large died in 1939, seventy years after the most

memorable day of his life.

No comments:

Post a Comment