This year for Veterans

Day instead of my usual post on the history and meaning of

the observation the World War I Armistice on November 11, 1918 I

thought I would resurrect an old chestnut that I first read as a Chalice

Lighting to open services at the old Congregational Unitarian

Congregation in Woodstock, Illinois about 2000. I read it subsequently when the congregation moved

and was renamed the Tree of Life UU Congregation in McHenry. It was included in my 2004 Skinner House

collection, We Build Temples in the Heart.

It was based on

the memories of a boy from Cheyenne in the 1950s. Reviewing it now, I am struck that the World

War II is fast fading away.

In not too many years the last of them will gone, just as

I remember the passing of the last World War I vet at the age of 110 in

2011. The cohort of their children,

the so-called Baby Boomers are fast aging as well. I am 72 and friends with parents who

served in what Studs Terkel called the Last Good War are about

the same.

It occurs to me

now that my grand children won’t understand much of what I wrote

about. They live in a different world. World War II and post-war America are

decades older for them than the Great War was for me. Neither will they know or care about our Vietnam

War choices obliquely referenced in the last lines.

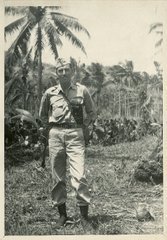

Pictures,

Poppies, Stars and Generations

We knew war.

Somewhere in

every home a handsome young man

peered from a tinted photograph,

overseas cap at a jaunty angle

or the fifty-mission

crush

or the crisp, square

beanie of a gob.

usually someone’s Dad in some other

life,

but sometimes the ghost of someone

frozen in time,

caught in that picture like a fly in

amber

while bloody shreds were left draped

on barbed wire

ten feet from the high water on an

anonymous beach,

or splattered on the glass of the

ball turret

of a Mitchell bomber spiraling for

an appointment

with a German potato field,

or bobbing in a sea of burning oil,

naked and parboiled.

We knew

pity.

The veterans

in neat blue uniforms,

sleeves pinned to shoulders, ears

shot away,

noses burned off, faces twitching,

fistfuls or red paper poppies in one

hand,

shaking white cans for nickels with

the other.

on every street corner, May and

November

and no decent man or woman passed

without emptying pockets of change,

twisting flowers into buttonholes,

on to purse straps,

without ever looking the peddler in

the eye.

We knew

death.

Inside

scrapbooks with brittle pages and fading ink,

kept far up in the front hall closet

behind hatboxes,

surrounded by last winter’s scarves

and mittens,

between the leatherette boards bound

by black shoelaces,

amid the rations coupons, V-mails,

postcards from exotic ports, Brownie

snapshot,

campaign maps, and yellowed

clippings,

a small fringed flag,

white edged in red and

blue,

a gold star in the

center.

In the

neighborhood we looted footlockers and duffel bags,

saved our allowances for forays to

the Army/Navy Store,

outfitted ourselves in helmet

liners, webbed belts,

canteens and mess kits, cast–off

khaki and drab,

and amid the prairie

burrs and grasses,

between the wild rose

hedge and lilac caves,

on top of the car port

in the window wells,

every summer day we

tried to sort glory from horror.

We knew war

and pity and death—

we thought.

And then—suddenly—it

was our turn for real.

—Patrick Murfin

No comments:

Post a Comment