Maybe

it’s the panting after a trip to the grocery store, the pain

in my knee and various other body parts, or strapping a breathing

gizmo to my face when I go to bed, but I feel more like the Old

Man every day. Without being morose

I feel my mortality slipping away day by day. Not that I plan to check out any time

soon. At least a couple of doctors recently

assured me that I will be around and annoying for the foreseeable

future with just a few lifestyle adjustments—cutting out sugar and

the kind of moderate exercise I can actually do.

But

like a lot of geezers past whatever landmarks are meaningful to

them, I have been thinking a lot lately about being an old man. I found some other poets who have been

doing the same—white men all and only three out of five of them dead.

The

first poem on the subject that caught my attention was To Be a Danger by

C.G. Hanzlicek who was born in Minnesota to a Czech immigrant

craftsman and a farmer’s daughter.

He made it into the University of Minnesota where he became

interested in poetry. Hanzlicek is the author

of nine books of poetry: Living in It, Stars, winner of the 1977 Devins

Award for Poetry; Calling the Dead; A Dozen for Leah;

When There Are No Secrets; Mahler: Poems and Etchings; Against

Dreaming; The Cave: Selected and New Poems; and, most

recently, The Lives of Birds. In 2001, he retired from California

State University, Fresno, where he taught for 35 years and was for

most of those years the director of the Creative Writing Program.

To Be a Danger

Just once I’d like to be a danger

To something in this world,

Be hunted by cops

And forced into hiding in the

mountains,

Since if they left me on the

streets

I’d turn the country around,

Changing everyone’s mind with a

word.

But I’ve lived so long a quiet life,

In a world I've made small,

That even my own mind changes slowly.

I’m a danger only to myself,

Like the daydreaming night watchman

Smoking his cigar

Near the dynamite shed.

—C.G. Hanzlicek

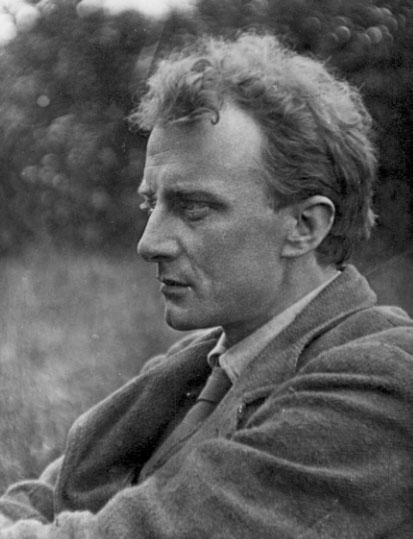

Ogden Nash.

Next

up is American comic poet Ogden Nash known for his short, pithy verses

and limericks. In this widely re-published

verse, a certain melancholy lurks behind the mirth.

Old Men

People expect old men to die,

They do not really mourn old men.

Old men are different. People look

At them with eyes that wonder when…

People watch with unshocked eyes;

But the old men know when an old man dies.

—Ogden Nash

Edward Thomas.

When the Great

War broke out. Already in his late

30s he vacillated over whether to enlist. Thomas enlisted in the Artists Rifles

in July 1915, despite being a mature married man who could have avoided

enlisting. He was influenced in this decision by his friend

the American Robert Frost, who had returned to the U.S. after

taking walking trips with Thomas. Frost

sent him an advance copy of The Road Not Taken. The

poem was intended by Frost as a gentle mocking of indecision,

particularly the indecision that Thomas had shown on their many walks together.

Most took the poem more seriously

than Frost intended, and Thomas took it personally, and it Edward

Thomas never actually got to be old.

The Welsh-born poet was already an established literary figure

provided the last straw in his decision to enlist. Thomas was promoted to corporal, and

in November 1916 was commissioned into the Royal Garrison Artillery

as a second lieutenant. He was killed in action soon after he arrived

in France at Arras on Easter Monday, April 9, 1917.

Old Man

Old Man, or Lad’s-love,—in the name there’s nothing

To one that knows not Lad’s-love, or Old Man,

The hoar-green feathery herb, almost a tree,

Growing with rosemary and lavender.

Even to one that knows it well, the names

Half decorate, half perplex, the thing it is:

At least, what that is clings not to the names

In spite of time. And yet I like the names.

The herb itself I like not, but for certain

I love it, as some day the child will love it

Who plucks a feather from the door-side bush

Whenever she goes in or out of the house.

Often she waits there, snipping the tips and

shrivelling

The shreds at last on to the path, perhaps

Thinking, perhaps of nothing, till she sniffs

Her fingers and runs off. The bush is still

But half as tall as she, though it is as old;

So well she clips it. Not a word she says;

And I can only wonder how much hereafter

She will remember, with that bitter scent,

Of garden rows, and ancient damson-trees

Topping a hedge, a bent path to a door,

A low thick bush beside the door, and me

Forbidding her to pick.

As

for myself,

Where first I met the bitter scent is lost.

I, too, often shrivel the grey shreds,

Sniff them and think and sniff again and try

Once more to think what it is I am remembering,

Always in vain. I cannot like the scent,

Yet I would rather give up others more sweet,

With no meaning, than this bitter one.

I have mislaid the key. I sniff the spray

And think of nothing; I see and I hear nothing;

Yet seem, too, to be listening, lying in wait

For what I should, yet never can, remember:

No garden appears, no path, no hoar-green bush

Of Lad’s-love, or Old Man, no child beside,

Neither father nor mother, nor any playmate;

Only an avenue, dark, nameless, without end.

—Edward Thomas

Robert Frost.

Speaking

of Frost, we naturally assume that New Hampshire’s beloved poet

would have something to meditate on.

Frost was adept at capturing scene and mood while reveling

in his craftsmanship with verse.

Here he found pathos in an elderly man’s isolation and loneliness.

An Old Man’s

Winter Night

All out of doors looked darkly in

at him

Through the thin frost, almost in

separate stars,

That gathers on the pane in empty

rooms.

What kept his eyes from giving back

the gaze

Was the lamp tilted near them in

his hand.

What kept him from remembering what

it was

That brought him to that creaking

room was age.

He stood with barrels round him—at

a loss.

And having scared the cellar under

him

In clomping there, he scared it

once again

In clomping off;—and scared the

outer night,

Which has its sounds, familiar,

like the roar

Of trees and crack of branches,

common things,

But nothing so like beating on a

box.

A light he was to no one but

himself

Where now he sat, concerned with he

knew what,

A quiet light, and then not even

that.

He consigned to the moon,—such as

she was,

So late-arising,—to the broken moon

As better than the sun in any case

For such a charge, his snow upon

the roof,

His icicles along the wall to keep;

And slept. The log that shifted

with a jolt

Once in the stove, disturbed him

and he shifted,

And eased his heavy breathing, but

still slept.

One aged man—one man—can’t fill a

house,

A farm, a countryside, or if he

can,

It’s thus he does it of a winter

night.

—Robert Frost

Of

course, the Old Man has chipped in too, relatively unembarrassed to

hitch his wagon to his betters. Take this from last Fall.

Equinox Eve Morn

September 21, 2021

Murfin Estate

Crystal Lake

The first few leaves

flutter down

from the old, slowly dying Boxelder

in the breaking grey light of dawn,

most of the thinning leaves not yet

turned.

The vigorous

five-trunk silver maple

whose crown enlaces it

has not even begun to turn

nor have any of the other trees

on our small lot.

A wind from the far-off

Lake

breaks yesterday’s heat and

humidity,

on cue the seasons are shifting.

Like that old junk

tree

I can feel myself dropping my own

leaves

tentatively but surely.

My time, too, is

slipping away.

—Patrick Murfin

No comments:

Post a Comment