In 1835 the New York neighborhood known as Five

Points was centered on an intersection

created by Orange Street, now Baxter Street; Cross Street, now Mosco

Street, and Anthony Street, now Worth Street which ran northwest

direction, dividing one of the four corners into two triangular

blocks. After London’s East End

it was the most densely populated,

disease ridden, and squalid slum in the Western

World. Built around 1811on reclaimed land where the Lenape Indians once had a fishing

village, it began to sink back into the mire and was plagued by

disease carrying yellow fever mosquitoes

and cholera breeding drinking

water polluted by human

waste. Middle class residents fled the area within a few years leaving it

to the most despised inhabitants of the city including a remnant of

the Lenape, known locally as the Canarcies,

Blacks including many who had been freed

in the culmination of New York State’s

gradual emancipation in 1827, and beginning about the same time the first

wave of immigration by impoverished displaced Irish Catholic tenant farmers.

A few years later Charles Dickens described Five Points

in his book American Notes:

What place is this, to which the squalid street conducts us?

A kind of square of leprous houses, some of which are attainable only by crazy

wooden stairs without. What lies behind this tottering flight of steps? Let us

go on again and plunge into the Five Points....

This

is the place; these narrow ways diverging to the right and left and reeking

everywhere with dirt and filth. Such lives as are led here, bear the same fruit

as elsewhere. The coarse and bloated faces at the doors have counterparts at

home and all the world over....

Debauchery

has made the very houses prematurely old. See how the rotten beams are tumbling

down, and how the patched and broken windows seem to scowl dimly, like eyes

that have been hurt in drunken forays. Many of these pigs live here. Do they

ever wonder why their masters walk upright instead of going on all fours, and

why they talk instead of grunting?

It was an uneasily integrated community with the Blacks

and Irish often brawling in the streets while consorting in the taverns and beer halls and sometimes even cohabitating. The two groups were united mainly

in the need to defend themselves from the depredations of native

Protestant gangs. In

1835 the Nativists had rampaged

through the neighborhood during the Anti-abolitionist

riots burning Black homes and churches and murdering any they found

on the streets. Organized politically as

the Know Nothings the same goons rose to local political power

on an anti-Catholic and anti-Immigrant platform and its gang

member supporters attacked Catholic churches, schools, and businesses.

On May 4, 1835 a number of

disgruntled Irishmen met at nearby St. James Church to devise a plan to defend

their community. They had a model—the Hibernians, a super-secret

society many had belonged to in the Ould

Sod which defended Catholics from the persecutions of the English and the local Protestant elites by violence if need be. They named their new organization in the

States The Ancient Order of Hibernians

(AOH) subservient to the

secret societies in Ireland. They even

got the organization a New York State

charter, making it official, something that the outlawed organization in Ireland could never be. Despite this overt step, they took pains

to make the proceedings and activities of their new organization secret

from prying eyes.

The origins of the Hibernians

in Ireland are shrouded in mystery and

myth.

The AOH itself traces the linage to Rory O’Moore, a Catholic nobleman

who organized secret Defenders against

the Earl of Essex Thomas Radcliffe,

famed as the lover of Queen Elizabeth I,

who was made Lord-Lieutenant of

Ireland in 1562. Essex prohibited

all monks and priests from either eating or sleeping in Dublin,

ordered the head of each family to attend Protestant services every Sunday

under the penalty of a fine, and perhaps worst confiscated the

property of Catholic nobles.

First off, the Hibernians get it

wrong, it was not Rory O’Moore a/k/a Sir

Roger Moore who was born about 1600 but his uncle, the clan chief Ruairí Óg Ó Mórdha, King of Laois that waged war on

Essex.

Rory came along two generations later and was one of the four organizers

of the Rebellions of 1641, a failed coup d’état by the ancient Catholic

nobility against authorities at Dublin

Castle then fought the prolonged Irish

Confederate Wars which took back much of the country outside of

Dublin. Then he resisted the invasion

by Oliver Cromwell but ultimately

was crushed and died in hiding or exile.

It is doubtful that there was any

direct organizational connection between the followers of either Ruairí Óg Ó

Mórdha or Rory O’Moore and the later Hibernians except by way of inspiration

for Catholic resistance.

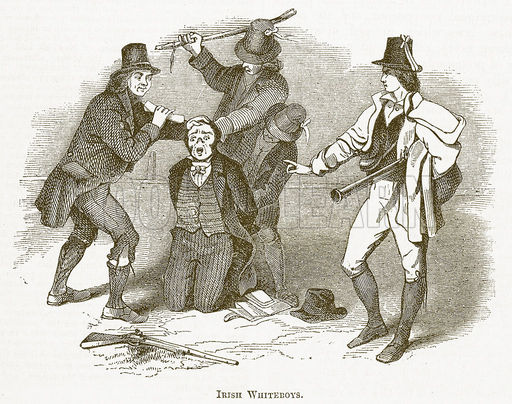

18th Century Whiteboys, a secret society of Irish tenant farmers, attack a landlord's agent in this British illustration. The Whiteboys were among the inspirations for the establishment of the Hibernians.

In the 18th Century for instance rural Catholic tenant farmers organized secret Whiteboy societies to protest

rack-rents, tithe collection,

evictions, and other oppressive acts by night

raids on landlords,

burning barns and estates, assaults, and assassinations. The name derived

from the white peasant smocks many

of the night raiders wore. At the time

the authorities called them Levelers and

they called themselves by different names including Queen Sive Oultagh’s Children, Fairies,

or followers of Sheila Meskill. There were three outbreaks of Whiteboy

violence—1761–64; 1770–76; and 1784–86 with

low level activity in between. Each

outbreak was ruthlessly and violently suppressed leaving parts of some

counties wastelands. Some of the surviving Whiteboys rallied to the United Irishmen uprising and the small French invasion force dispatched by Napoleon in 1798. But others were deeply distrustful of

the United Irishmen which was largely led by liberal Protestant Dissenters.

The spirit of the Whiteboys,

if not their organization, was revived around 1813 by the Ribbonmen, an agrarian Catholic secret society formed

to prevent landlords from evicting their tenants. The also attacked tithe and process servers. Strongest in Ulster, they became deadly enemies of the Protestant Orange Order and the two

groups often fought pitched battles.

The Ribbonmen were named for the bits of green ribbon they wore

in their buttonholes, but they called their organization the Fraternal Society, the Patriotic

Association, or the Sons of the Shamrock. It was to the secret leadership of these

societies that the new American AOH pledged

their allegiance in 1835.

The AOH grew rapidly despite the

secrecy with which it surrounded itself.

In New York City they organized patrols

armed with clubs and blackthorn sticks to defend Catholics,

particularly their Churches and Priests

from assaults by Nativist gangs. More

importantly, they began organizing politically

and within a few years wrestled control of the 6th Ward whose heart was Five Points from the Nativist Tammany Wigwam and elected Irish

Catholics to local office—the first time this kind of political success

was had by the Irish in this country and a model

in embryo for the political

machines they would come to command in many cities.

A second locus of growth in

the early years was at Pottsville, Pennsylvania in the heart of the state’s anthracite coal region where Irish

miners had been recruited to work the pits. It was extremely dangerous

hard work. Fourteen hour days, six

days a week were standard. Pit operators

often failed to meet payrolls and levied fines for minor offensives and made employees pay rent on tools and equipment.

Trade unions were in their infancy and manual laborers like coal

miners, especially Irishmen, were

not considered intelligent enough to

manage their own affairs. A secret

society, like those of tenant farmers in the old country, seemed like the

natural way for the miners to organize to protect themselves. So, the

Hibernians spread over the coal fields.

After the Civil War the Hibernians were deeply established over the

anthracite district. By then they were operating

semi-openly as an ethnic benevolent

society, a type of organization that spread widely in the second half of

the 19th Century which, among other things, raised money for the many widows and orphans caused by frequent mine accidents, fires, and shaft collapses. The men could assemble for

meetings—invariably on Sundays after Mass, the only time of the week they were not working—without

attracting too much attention. But what

went on in those meetings was an oath

sealed secret.

Conditions in the mines had grown

worse under the insatiable demand for fuel for the emerging steel industry, other heavy industry, and the ever-expanding network

of railroads knitting the

country together. New mines opened

regularly. Ownership in many cases

passed form individual entrepreneurs

to corporations and consortiums tied to the steel industry

meaning that the real bosses were

far away and seldom seen. Demand for

increased production meant corners were cut to already scant safety procedures including

inadequately timbering the shafts

and careless handling of black powder explosives led to ever

more dangerous working conditions. To

work the mines the bosses turned increasingly to children for jobs away from the mine face, especially as breaker

boys. By 1870 nearly a third of all

workers in the district were boys 16 years of age and under, numbering more

than 10,000.

Worst of all from the perspective of

the Irish miners, who were relatively established in the district, was the

importation of non-English speaking

immigrants, especially Italians and

Slavs to work the mines. Not only were these newcomers considered

dangerous to work alongside because they could not speak English and were un-instructed

in even rudimentary safety practices, but they were paid even less, driving

down wages across the district.

Suddenly the Irish were in the same boat as their old Know Nothing and nativist enemies and they behaved in much the same way to the newcomers.

Some early attempts at unionizing

the field began in 1869 with the Workingmen’s

Benevolent Association (WBA) after a particularly gruesome Avondale mine disaster took the lives

of 110 miners—just some of 566 miners had been killed and 1,655 maimed in Schuylkill County alone in a seven year

period. The attempt to unionize was met

by violent repression by the bosses, including almost daily beating of

suspected members as well as a number of ambush

shootings. All of this intensified

after the Panic of 1873 brought

rounds of wage cuts across the

district.

The time was ripe for the Molly McGuires. Historians are divided three ways

concerning the Mollies—that they and the Hibernians were virtually one and

the same, that the Mollies simply took advantage of the Hibernian

meetings to infiltrate the organization and use its secrecy to plan

their operations, or finally that there never was a real organization of

Mollies at all except for possibly individual or small groups of men inspired

the legend to act on their own against their immediate exploiters. Only those who are apologists for the employers’ version of history,

including some modern Libertarians

maintain that the Mollies and Hibernians were the same organization. The second viewpoint is the most widely held

and the third, that the Mollies did not really exist at all, is held by a

number of labor historians.

Back in Ireland secret groups identifying

themselves as Molly McGuires began to emerge during the Potato Famine. They

were even more rural, local, and Gaelic than the previous

Ribbonmen. Local Molly leaders were

reported to have sometimes dressed as women as cover for

their attacks. Membership and/or

activity in the Mollies against the landlords and abusive merchants

may—or may not—have coincided with the shadowy Irish Hibernians to whom the AHO

owed fealty.

At any rate a rash of counter-violence

including the murders of pit bosses,

foremen, and suspected spies, as well as sabotage of the mine shafts and heads with the placement of black powder bombs was soon being blamed

on the Molly McGuires and the AOH lodges were suspected to be the center of a vast

conspiracy.

In 1873 Franklin B. Gowen, the President

of the Philadelphia and Reading

Railroad, and of the Philadelphia

and Reading Coal and Iron Company and the wealthiest anthracite coal

mine owner in the world, hired Allan

Pinkerton’s detective service to deal with the supposed

Mollies. But his real target was

the WBA, which had grown to claim a membership of thirty thousand—85% of

Pennsylvania’s anthracite miners and a real threat to mine owners profits. The leadership of the WBA was not Irish but were

English Lancastershire miners who

were adamantly opposed to violence

and known to be trying to crack down on the acts credited to the

Mollies. Pinkerton was instructed to

gather evidence that would tie the WBA and its leadership, as well as the

AOH. Out of 450 Hibernians in Schuylkill

County, 400 were found to be union members.

In 1874 Pinkerton assigned one of

his top agents, 30 year old James

McParland who was born in County

Armagh, to infiltrate the

AOH. Working as a miner under the name

of James McKenna McParland seemed to

have no trouble infiltrating the Hibernians and gaining the trust

of leading members. He sent detailed

daily reports to his employer.

McParland showed a basic ignorance of the history of the AOH when

he wrote that the lodge was created by the Mollies as a cover for their

activities, despite the fact it had been active for decades before the violence

attributed to the Mollies ever began. He

also complained in his reports that he was making little progress in tying the

Hibernians to the Mollies. He was, however,

readily able to identify a number of union members.

In response to a general 20% wage

cut announced by Gowen’s Schuylkill

Coal Exchange combination of mine operators, the WBA went out on strike

on January 1, 1875. It would be a long strike,

punctuated by violence by the notorious Pennsylvania

Coal and Iron Police, the Pennsylvania Militia, and vigilantes on

one hand and retaliation attributed to the Mollies on the other.

Pinkerton either turned over

or allowed employees of Gowen to have access to the identity of the

union members uncovered by McParland. He

also recommended to Gowen that vigilantes be formed to attack known unionists,

supposedly in revenge for Molly attacks.

A union leader and AOH member Edward

Coyle, was murdered in March. Another member of the AOH was shot and killed

by the Modocs, a Welsh gang operating led by a mine

superintendent. Another mine boss, Patrick Vary, fired into a group of

miners and, according to the later boast by Gowen, as the miners “fled they

left a long trail of blood behind them”. At Tuscarora, a meeting of miners was attacked, and one miner was

killed and several others wounded.

Then on December 10, 1875, three men

and two women were attacked in their home by masked men. One of the men

and one of the women, the wife of a miner, were killed. The other two men were able to escape with

wounds, although McParland would later charge that they were hunted down and

killed by the Coal and Iron Police. The

vigilante raid outraged McParland who had no objection to the

assassination of union men but was furious that his reports had been used to

murder a woman who he considered innocent. He angrily submitted his resignation but was

enticed to stay with promises that his notes would no longer be turned over to

vigilantes. His scruples salved, McParland withdrew his resignation—and Gowen

continued to turn over the names of union members he identified to the

vigilantes.

First

Lt. Frank Wenrich, of the Militia, was eventually arrested as the

leader of the vigilante attackers but released

on bail and never tried.

Violence and retaliation continued

on both sides while Union leaders appealed for calm and tried to arrange arbitration. In May of 1875 28 national and local

union leaders were arrested. They were

all convicted at trial for conspiring to raise wages depressing the price of a vendible commodity and sentenced to a year in jail. With the WBA leadership in jail, the strike

struggled on loosing strength day by day, but violence on all sides

escalated, especially since the strongest voices for peace on labor’s side had

been effectively silenced.

After six months with their families

starving the strike and union was broken.

The men returned to work accepting the 20% pay cut and many were black balled from ever working in the

mines again. The end of the strike,

however, did not end the violence with both vigilantes and alleged Mollies

committing revenge murders well into 1876.

McParland now announced he had at

last been able to identify suspects in several planned or executed murders and

bombings. In the end several men went to

trial on murder or attempted murder charges based on McParland’s reports and

testimony beginning in January 1876.

Mine boss Gowen got himself named as special prosecutor in the case.

In all ten men were convicted and sentenced to hang. One man, Jimmy

Kerrigan, the brother-in-law of McParland’s fiancé, was acquitted in a second trial after an initial mistrial. On June 22, 1877 the ten men were hanged in

two batches, six at the prison at

Pottsville, and four at Mauch Chunk, Carbon County.

Another ten men were convicted and

hanged on evidence not from McParland and a last accused Mollie was tried and

hung in 1878. All of the dead were

identified as Hibernians and most as union members.

The Hibernians, union, and the

Mollies were all shattered. The national

leadership of the AOH far from supporting their accused brothers, denounced

them and officially dissolved the “guilty” lodges and expelled

all the members in an attempt to mollify public anger.

The Hibernians remained active in

both the United States and Ireland, however.

Increasingly tied to the Church, they became the extremely conservative wing of the Irish Nationalist Movement. In

Ireland it still did not have an official form

or identity. Many of its leaders were supporters of Charles Stewart Parnell’s Irish

Parliamentary Party. They were the

bitter enemies of the more secular Irish

Republican Brotherhood (IRB)

just as the AOH in America opposed the IRB’s allies here, the Fenian Brotherhood.

An Ancient Order of Hibernian gathering at Hinkle Town, Iowa circa 1880.

In the U.S. the Hibernians split in

1884 between a minority that supported a continued allegiance to the Board of Erin consisting exclusively of

Hibernians in Ireland and Britain and a much larger group that wanted American

elected officers. The majority

became the Ancient Order of Hibernians

of America and the smaller group called itself Ancient Order of Hibernians, Board of Erin. By 1897 the Board of Erin group had only

40,000 members in pockets around New York city and in Illinois while the AOHA boasted 120,000 in every state. In addition, the AOHA chartered a ladies auxiliary, The Daughters of Erin in

1894 that had more than 20,000 members.

The two groups re-united in 1898 under the American leadership but

expressing a special relationship with Hibernians in Ireland.

The Irish Hibernians finally got legal

status in the 1890’s under the leadership by Joseph Devlin of Belfast. Heavily concentrated in Ulster, now also officially the Ancient Order of Hibernians spent much

of its time challenging the Orange Order

and contesting its annual Twelfth of

June Marches commemorating

the Protestant victory at the Battle

of the Boyne. That single mindedness

proved very popular in Ulster where membership blossomed from 9,000 members at

the turn of the century to 64,000 in

1909. They also began to make inroads

elsewhere in Ireland, but their extreme sectarianism

was viewed by many in the South as an impediment to retaining

the support Protestant Dissenters and even making inroads among the Anglo-Irish of the Church of Ireland.

The Hibernians were among the first

to openly recruit and train an armed militia of their

own. They generally opposed the

raising of Irish regiments and troops for The Great War

and entered a somewhat shaky alliance with the emerging Irish Volunteers. They bitterly opposed the James Connolly’s socialist and labor Irish Citizen Army. None-the-less one company of Hibernian Rifles joined the Volunteers

and Citizen Army in the 1916 Easter

Rebellion.

A Hibernian Rifles uniform (left) from the Easter Rebellion next of a Irish Citizen Army uniform of James Connolly's labor and socialist militia.

During the War of Independence many Hibernians joined the Irish Republican Army but in the Civil War that followed they supported the government and

Treaty Forces. Its influence waned outside of Ulster,

and even on its home ground. By the

1930’s they were drifting to fascism

and supplied troops to the Irish

Brigade fighting for Franco in

the Spanish Civil War.

In Ulster the Hibernians had long

sponsored their own proactive parades to taunt the Orangemen. At the beginning of the Troubles in 1968 they voluntarily called off their annual

marches in the interest of peace but resumed them in 1975 as the

organization became increasingly identified and allied with the

nationalist Provisional IRA.

Today only a few thousand strong its

mostly elderly members continue to confront their ancient enemies

yearly.

In the United States the AOHA

remained active, although organizations more directly connected to arming and

supplying the IRA gained popular support.

In 1965 they reported 181,000 nationwide. Like all fraternal organizations in this

country, membership dropped precipitously over the next few years as

elderly members died with no youthful replacements in sight.

Less than 10,000 remained when a

revival of sorts began in Montana with

the establishment of the vigorous Thomas

Francis Meagher Division No. 1, named for the Civil War General of the Irish Brigade, and Montana Territorial Govern in Helena, in 1982. Within a couple of years six more Montana

towns formed units. Other new divisions

were founded in California and in

2018 a new division was founded in Tennessee. Several Divisions have lately been

successful in recruiting young members.

The order organized the New York City St Patrick's Day Parade

for 150 years until 1993, when control was transferred to an independent

committee amid controversy over the exclusion of Irish-American gay

and lesbian groups.

No comments:

Post a Comment