Thanks to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow he is one of the few original

settlers of Plymouth Plantation who most people know by

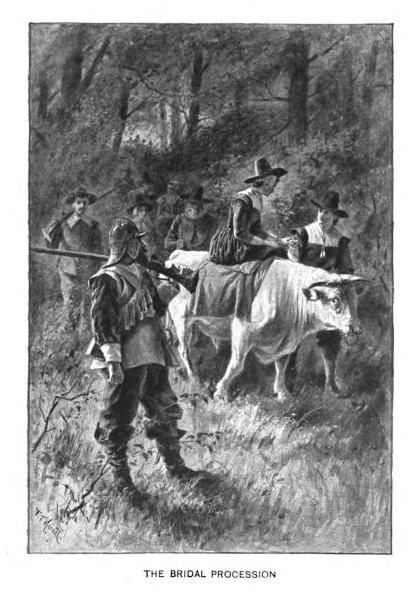

name. The Courtship of Miles Standish, Longfellow’s

long poem, was among the most beloved verses of the 19th Century and snatches of it were recited

by school children who learned

it by rote. While seldom read these days many still

know the central story of how a shy, tongue-tied soldier

asked his best friend John Alden to

speak to the object of his affection, Pricilla Mullins,

and how she told John to “Speak for yourself” if only because the story was

lampooned in Loony-Tune cartoons and

on the Rocky and Bullwinkle Show.

Of course, the poem and story were largely romantic nonsense, but as P.T. Barnum allegedly once observed, “There is no such thing

as bad publicity.”

The real Captain Myles Standish died peacefully in his bed on his farm on

October 3, 1656 in Duxbury, age

about 72. His story is much more interesting

that Longfellow’s romance.

Maddeningly little is known for sure

about Standish’s early life. No official records or mention of his name can be found before 1620 in Leiden, Holland shortly before he hired himself out to a sect of English Separatists for their New

World colonizing project. By then he

was about 36 years old.

Evidence—Standish’s will

and later testimony of at least one

of those who knew him in the Plymouth colony as well as what is inferred by the

name Duxbury for the village he founded—strongly suggests that he was

probably born in Lancaster where a wealthy Standish family had several estates including Duxbury Manor, which some conjecture might have been his childhood

home. In his will Standish referred

to estates in “Ormskirke (Ormskirk) Borscouge (Burscough) Wrightington Maudsley Newburrow (Newburgh) Crowston (Croston) and

in the Isle of Man which allegedly

were his rightful inheritance. He said these were “Surruptuously

detained from mee My great Grandfather being a 2cond or younger brother from

the house of Standish of Standish.”

But no parish records, which may have been destroyed during the English Civil War, can confirm his birth and lineage and no court records

document disputes over these properties.

Some historians have postulated that he actually came from a

branch of the family on the Isle of Man, but not documents support that,

either.

His friend Nathaniel Morton, Secretary

of Plymouth Colony, who wrote in his New England’s Memorial, published in

1669, that Standish was:

...was a gentleman, born in Lancashire, and was heir

apparent unto a great estate of lands and livings, surreptitiously detained

from him; his great grandfather being a second or younger brother from the

house of Standish. In his younger time he went over into the low countries, and

was a soldier there, and came acquainted with the church at Leyden, and came

over into New England, with such of them as at the first set out for the

planting of the plantation of New Plymouth, and bare a deep share of their

first difficulties, and was always very faithful to their interest.

This is pretty strong evidence but

does not meet the standards of rigorous documentary evidence that

those sticklers, genealogists demand

as proof.

Whatever the case, the young man

found himself cast upon the world to shift for himself. He chose the gentleman’s profession of arms, but his family seems to have been too poor to afford to purchase

a commission in the Army.

Standish apparently found himself in

Holland where the Dutch Republic was

embroiled in the Eighty Years War (1568–1648)

against Spain. He likely, at least initially, sold his

services to the Republic as a soldier of

fortune. When English Queen Elizabeth authorized a force

under Sir Horatio Vere to aid the

Dutch and serve under the authority of the Estates

General, Standish was almost surely in that force and engaged at least for

the Siege of Sluis in 1604. Indirect evidence is that he may have been a Lieutenant under Vere.

The war was interrupted by

the Twelve Years Truce from 1609 and

1621, which may have rendered Standish unemployed. Or he may have been retained in service to

the Republic, probably at half pay

in case of the resumption of hostilities. At any rate, he chose to remain in Holland

and eventually settled in Leiden where he married an English woman, Rose Handley about

1618.

It is there when we first find

reference to Standish. He is identified

as Captain, but how or why he came

by the rank is unknown. He was, however, locally well-known and respected as a soldier. He was acquainted with the English

Separatists who settled there from about 1608.

He may have found his wife, Rose, among them.

When the Separatists determined to

leave Holland for the New World,

Standish was a natural candidate for

the important post as military advisor to

the expedition. But he was not the only one. The Separatists’ financial backers favored the swashbuckling

Captain John Smith, then in England, who was familiar with the New World

and whose writings about the Colony of Jamestown and of Virginia in general had made him famous. Smith was interested in the job, but his

price was too high and Separatist leaders

John Robertson and William Brewster were concerned that

the domineering Smith might try to

establish a dictatorship over their

people in their new home. Standish got

the job.

On September 6, 1820 Myles and Rose

Standish were among the 102 passengers and

30 crew who set sail from the port of Plymouth. Standish and a

handful of other passengers were not Separatists but hired help. The men of the

religious community were largely gentlemen,

heavy on ministers, deacons, lawyers, and merchants. They needed a few skilled tradesmen, and at least one soldier, to survive in the

howling wilderness.

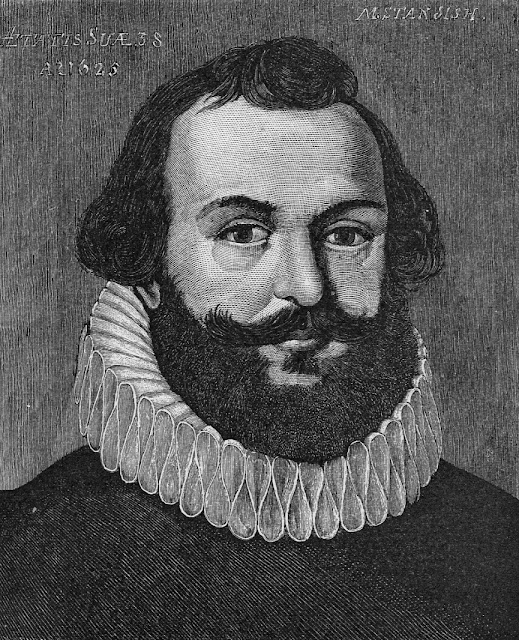

Standish was a short, but powerfully built man, standing probably

about 5 foot 3 with the bushy beard favored by soldiers of the

day to make them seem fiercer. His stature made him the subject of jests by others on board and latter his

Native enemies mocked him for

it. Despite his size, by the time the Mayflower

completed it hazardous voyage Standish

was recognized as one of the key leaders of the company.

The Mayflower was stalled not far from England by contrary

winds delaying the crossing and driving it far north of the intended

landfall in Virginia. Land was sited—Cape Cod—on November 9. Attempts to sail

south were thwarted by seasonal winds,

already in winter mode. With shipboard supplies nearly exhausted

company leaders reluctantly decided that they would have to make landfall and establish a community

before the full force of winter. But

this would leave them beyond the authority of their charter.

On November 11 the company gathered

on board to draft and sign what has become known as the Mayflower Compact,

the first written charter for self-government

in the world. Standish’s place among

the leadership was demonstrated when he became the fourth person to sign the document, by far the highest standing

of a Stranger among the Saints.

Standish took a leading role in trying

to find a suitable place to establish themselves. On November 15 he led a party of 16 men from

the ship exploring the northern hook

of Cape Cod on foot and on December

11 he was with or leading another party that explored the shoreline by

boat. During this investigation, the

party would spend nights ashore behind makeshift

barricades of driftwood and tree branches erected at Standish’s

insistence.

One night near present day Eastham, the party was surprised and attacked by as many as 30 natives. Standish reportedly calmed a near panic and

kept the men from wildly firing their arquebus

matchlocks. With disciplined fire,

the attackers were driven off. This

incident became known as the First

Contact and shaped the thinking of both Standish and the other

settlers about their prospective neighbors.

In late December the final location

on Plymouth Bay on the mainland was agreed upon. Standish laid out the small fort to be equipped with the ship’s cannon and the positioning of a cluster of houses

for maximum defensibility against

expected native attacks. Unfortunately,

only one house was completed by the time devastating

illness struck the community—likely a combination of dysentery from drinking brackish

water and pneumonia attacking

those who were already weakened.

Many were forced to winter in crude huts. Loss of life from disease and exposure was devastating. The colony lost half of its members that

winter, including Rose Standish who died in January. The sturdy Standish was one of the few who

did not fall ill and spent much of the winter nursing the sick and trying to get the few semi-able-bodied men to continue what

work on the settlement could be done during the harsh weather and stand watch

against possible native attacks.

By late February the colonists began

to note movements of natives in the woods

around them—the tribes had mostly stayed in their villages over the winter

subsisting on stored grain and jerked meat. Alarmed, the surviving colonists met formally

to elect Standish Captain of the Militia and giving him full authority to raise and train a

company. Standish put all able bodied

men under arms and regularly drilled them with their arquebus muskets and halberd pikes, a weapon totally unsuited for wilderness

combat. But the natives undoubtedly

observed the preparations and may have been impressed.

In March Samoset, a Sagamore, an Eastern Abenaki tribe, who was on an extended visit to

the local Wampanoag, casually walked into the settlement,

greeted the white men in English, and asked for beer. Samoset had learned English from fishermen along the shores of present

day Maine where his tribe

lived. A few days later he returned with

Tisquantum—Squanto—a Patuxet who

had been kidnapped and taken as a slave to England, only to find his way home

years later and discover his people wiped out by an epidemic.

Samoset

and Tisquantum arranged a meeting with Massasoit,

the sachem of Pokanoket tribe of the Wampanoag Confederacy. The Pokanoket were constantly under threat by

more powerful tribes including the Massachusett

and the Narragansett. They were happy to conclude a treaty of friendship and mutual defense with Plymouth under the leadership of its first Governor John Carver. Standish concurred, in the belief that

having native allies would be essential in defending his weakened

colony.

He

quickly became close to Tisquantum, the homeless native who spent more and more

time in the settlement and famously introduced the colonist to native agricultural practices for the raising

of corn and squash. The resulting harvest that Fall, along with hunting saved the colony from a second

winter of starvation.

Later

in the summer of 1621 Governor Carver died and his deputy William Bradshaw succeeded him.

Standish was even closer to Bradshaw, who he had known since Leiden and

nursed through the illness, than he had been to Carver. They two men, vastly different in

temperament, would become an unshakable

team.

The

first test of the Bradshaw-Standish partnership and of the alliance with the

Pokanoket came in August. Settlers at

Plymouth got rumors that a minor chief named Corbitant was plotting against Massasoit to turn the tribe against

the town and perhaps join a new confederation led by the Massachusett to drive them out. That rumor probably came from Tisquantum. Standish

and Brewster dispatched Tiquantum and Hobbamock,

a high ranking warrior and advisor to Massosolt, to investigate with a

visit to Corbitant’s village of Nemasket

14 miles west of Plymouth. Corbitant’s

scouts probably were aware of their departure from Plymouth almost from the

beginning.

Upon

arriving at the town, Corbitant attacked the two men and detained

Tiquantum. Hobbamock escaped and ran to

Plymouth to share the news. Bradford was

inclined to negotiate for their ally’s release. Standish believed it would be a sign of

weakness that would cause theme Pokanoket to abandon the alliance. He advocated a swift raid to release

the prisoner. Standish won out and on

August 14 he led ten men with Hobbamock as their guide determined to free the

hostage and kill Corbitant.

Standish

planned a night attack on the wigwam where Corbitant was believed to

be sleeping. Standish and Hobbamock

burst into the wigwam shouting for Corbitant, the frightened inhabitants

tried to flee. A man and a woman were shot and wounded. It was quickly determined that Corbitant had

been warned and fled the village and that Tiquantum was

unharmed. He joined the party on the

return to Plymouth along with the two wounded who were treated and nursed back

to health.

In

many ways the raid on Nemasket was a botched

operation. But it had the desired

results. Within a few days Corbitant

came in, re-pledged his loyalty to

Massosolt, and approved a treaty for his band with Plymouth.

This

was the first English offensive operation

against native people in New England and set a pattern of aggressiveness for future

confrontations. Many modern historians

have cast Standish as the prototype for

the reckless, headstrong, and violent settler

military leader, a type that would be seen over and over for almost the next

400 years. And there is a good deal of

truth in that.

Another

view is that at this time the Plymouth colonists were too weak to do anything

but fit into to an already existing

cultural pattern of alliances and

confederations engaged in warfare over

hunting grounds, fishing waters, and good land for their gardens. Plymouth was just another tribe, and a minor

one at that, fitting into such and alliance and participating in the give-and-take raiding that

characterized relatively chronic low

grade warfare. This may have been

the case until enough new settlers arrived from England to provoke an existential threat to the tribes.

Of

course, the alliance with the Pokanoket was strengthened. But their rivals were alarmed with the

addition of new enemies. One November a Narragansett messenger

arrived in Plymouth with a bundle of arrows wrapped in a snakeskin. Standish recognized it as a threat

and replied with a snakeskin bundle of his own wrapping gunpowder. War with the powerful

tribe to the south seemed inevitable.

By

the way, that harvest feast to which

the Pokanoket invited themselves and which Bradford mentioned in passing in his journal of the early years, Of Plymouth Plantation, was

held in the light of the evolving crisis.

This was the dinner which became mythologized

as the First Thanksgiving.

A sketch of the probable appearance of the Plymouth settlement circa 1627 based on archaeological evidence. Standish laid out the house lots for maximum defensibility and designed oversaw the construction on the Palisade.

Standish

now knew that local tribes were unlikely to attack during the winter. This gave the colony time to prepare. The Captain recommended the construction of a

palisade completely surrounding the settlement and taking

in a good source of fresh water and including some pasturage for

the small herd of goats and even

some garden plots. The palisade would have walls

totaling more than half a mile long and include a reinforced gate and elevated gun

platforms.

With

the arrival of more settlers on board the ship Fortune Standish had

about 50 able bodied men to work on the project over the winter. Snow

cover actually helped to drag logs

cut in the surrounding forest. Work was

completed in just three months by March 1622.

Then

Standish re-organized his militia into four companies—one assigned to

each of the four walls. Narragansett

scouts undoubtedly saw the preparations and were evidently impressed and intimidated. It they had ever actually planned spring

raids, they called them off.

The

next threat came from the Massachusett to the north and was triggered by the

establishment of another colony, Wessagusset

near the site of modern Weymouth

on the Fore River. This group, organized and sponsored by

merchant Thomas Weston was a

strictly commercial venture and the

settlers adventurers like those who

had settled Jamestown and other

places in Virginia. When they stopped at

Plymouth, Bradford found them coarse

and undisciplined. Certainly, the new group, which hoped to

thrive on a fur trade with the

tribes, lacked the cohesion, the sense of community and purpose of

Plymouth.

The

settlers at Wessagusset soon alienated the

Massachusett by cheating them in trade with shoddy goods and stealing whatever

they could lay their hands on. By March

1623 some Massachusetts sachems were planning to raid and wipe out Wessagusset and then attack Plymouth itself. At least that is what Massasoit reported to

Bradshaw and Standish. He also urged

them to strike first against the plotters.

Shortly

after Phineas Pratt arrived in

Wessagusset and confirmed that the town was being harassed and settlers were

afraid to leave for hunting. They were

threatened with starvation. After Bradford called a town meeting to

discuss the crisis, Standish organized a small party including his friend

Hobbamock and seven others to assassinate

the Masssachusett war leaders including Wituwamat

and Pecksuot.

When

he arrived at Wessagusset some settlers had abandoned the settlement

and were living among the Massachusett.

Standish sent runners to nearby villages calling the deserters to return. Pecksuot and other leaders of the war party came to the village. Standish claimed his party was merely there

for the fur trade. Pecksuot did not

believe it for a moment. He told

Hobbamock, “Let him begin when he dare...he shall not take us unawares.” Later he mocked Standish’s diminutives height

to his face.

Standish

invited Pecksuot to eat with him the next day.

He arrived with Wituwamat, a

teen age warrior, and several women.

When all were inside the one room house where the meal was supposed to

be shared, Standish’s men slammed and barred the door from

the outside while the captain leaped at Pecksuot, taking his knife away from

him and stabbing him multiple

times. Others killed Wituwamat and the

young warrior. Emerging from the scene

of the carnage, Standish ordered the others seized and killed. He then led his men out of the settlement in

pursuit of another sachem, Obtakiest. He soon found him and a group of warriors and

there was another skirmish in which Obtakiest managed to escape.

Standish returned in triumph to Plymouth bringing with him

Wituwamat’s head. The raid indeed

intimidated the Massachusett and other tribes, but it also infuriated them by

violating customs of hospitality and curtesy to guests. The Massachusett and other tribes boycotted trade with Plymouth,

depriving the colony of its chief source of income from furs. It took years to recover.

Wessagusset was soon abandoned by its settlers. A handful joined Plymouth, but most opted to

beat a retreat to the English fishing

outpost on Mohegan Island.

When the Separatist spiritual leader Pastor John Robinson back in Leiden heard what had happened he was

troubled by the treachery and brutality.

Bradford may have shared some of the qualms, but he stoutly defended his captain.

In 1624 Standish took a second wife, Barbara, whose last name has been lost in the mists of time. She

arrived in Plymouth with a wave of new settlers the year before. Some believe

she may have been a sister of Rose who he sent for. At any rate, the couple enjoyed a long

relationship and had seven children, five of whom lived to adulthood and

two of whom gave him 12 grandchildren.

One of them, Alexander,

married the daughter of John and Pricilla Alden. Thousands of Americans alive today can trace their ancestry to Myles Standish.

Standish’s next military adventure had him leading troops

not against any of the tribes, but against other English colonists. In 1625 another group of adventurers established and outpost they called Mount Wollaston 27 miles north of

Plymouth at what is now Quincy. If Bradford and the elders of the Saints

had found the settlers at Wessagusset rambunctious

and wanton, they were positively

scandalized by the men under the

leadership of Thomas Morton.

In England Morton had been a political radical,

rather than a religious zealot. He also was something of a freethinker before that term had been invented and an unrepentant libertine. He was frequently in hot water at

home for advocating for dispossessed

countrymen. He had already been to

Plymouth and disapproved of the Saints as much as thy disapproved of him. He had returned with a Captain Wollaston and 30 indentured

servants to set up a fur trading post for the interests of a Crown-sponsored trading venture. He caught Wollaston selling some of the

indentures into slavery in Virginia

and expelled him.

Instead, he and the remaining indentures set up something of

a utopian community which they

renamed Mount Ma-re or Merriemount. He declared the former indentures free men or consociates and encouraged them to integrate into the Algonquian culture of the nearby

tribes, including taking native wives or

concubines. Morton also freely traded muskets,

powder, and liquor to the tribes,

many of which were still shunning trade with Plymouth. Indeed by 1628 Merriemount was the fastest

growing and most economically

successful colonial settlement in New England exporting not only furs but surplus agricultural production and timber. That was a powerful economic

reason to hate the interlopers. But by adopting and celebrating the pagan ways natives, and casual sexual immorality Bradford had a religious excuse to attack.

The establishment of both Wessagusset and Merriemount was

possible because Plymouth was bound by its private charter to the Company of Merchant Adventurers and

limited to the original settlement and near environs. Its population had been swelling with the

regular arrival of more colonists from both Holland and England. Bradford wanted to be free of the obligations

to the Merchant Adventures and get a charter amended to include a wider area so

as to be able to establish new communities and control unwanted interlopers.

In 1625 he sent Standish back to England to try and

negotiate a termination or modification of the relationship with the investors. The Captain turned out to be a better soldier

than diplomat and returned to

Plymouth empty handed. The next year,

however, another agent, Isaac Allerton

secured an agreement to sever the relationship if the colony’s debt to

the Adventurers were paid off. Standish

was among the leaders who used their own private

purses to pay the debt allowing Plymouth Colony to allot land and

establish new communities in an area east of Narraganset Bay and south of

Massachusetts Bay including Cape Cod.

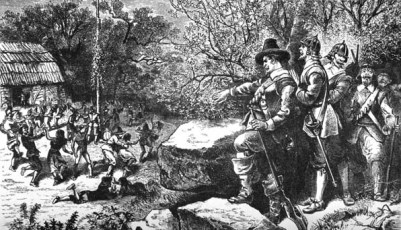

Armed with this new authority, Bradford turned his eyes on

Merriemount in1628, although Morton still had legal authority there and

powerful backers in England. The final

excuse for action was a report that in the spring of that year the inhabitants

there had erected a May Pole and had

engaged in lewd, immoral, and Pagan celebrations. The May Pole was a common country custom

in England even in that day. But it had

obvious pre-Christian origins as

part of a spring fertility festival which

the Catholic Church and the Anglicans had tried to adopt by making

it part of celebrations of the Month of

Mary. Both the Pagan and Catholic

connections made the May Pole and similar customs an anathema to the Separatists. Bradford had no trouble convincing the

town to raise a force to arrest Morton and disburse the community. Standish still had not joined the Saints, and

never would. Yet despite the aspect of a

religious crusade, he felt honor

bound by his duty as Captain of the Militia and deep loyalty to the Colony to

accept command.

Standish led a party on a raid. By their account upon arrival the settlers

retreated to a fortified house and prepared to defend themselves with arms but

were “too drunk to handle their weapons.”

Standish personally confronted Morton who leveled a musket at him which

the Captain tore from his hands before he could shoot. The raiders righteously chopped down the Maypole and brought Morton back to

Plymouth under arrest.

Morton, too influential in England to hang for blasphemy,

was marooned on an uninhabited island until some English

ship should find him and take him back.

He nearly starved to death, which was the plan, but friends from the

native tribes brought him occasional supplies until he found passage home. Morton returned once more to try and salvage

Merriemount, but was re-arrested, the settlement burned, and its few remaining

inhabitants scattered. Back in England

once more he would file a long fought court

case for damages in the affair and win considerable public sympathy.

Morton’s account in his book New English Canaan would

paint a vastly different picture than the account Bradford made in his journal,

which has been the accepted version

in this country. In it he called

Standish Captain Shrimp and wrote,

“I have found the Massachusetts Indians more full of humanity than the

Christians.”

Shortly after the Merriemount raid, Standish received his

land allotment from the entitlement of each head of household—male, of course—under the

new arrangement. As a high ranking civil

official, he presumably had an early option on site selection. His pick was prime land on the shore north of

Plymouth where he was allotted 120 acres.

Other senior officials and influential men including Bradshaw, John

Alden, and Minister John Brewster

also settled there. Standish is often

given credit as founder of the town on the strength of the name, which was a

Standish clan estate in Lancaster. Yet

no documentary evidence proves either assumption.

He built his house in 1628 and was living there in the

summers and wintering in Plymouth for the first years. He began to spend more time on the farm,

improving it and adding acreage and was spending most of his time there year

round by 1630.

In the eventful year of 1628 Plymouth seized possession of

the French fort and trading post of Fort Pentagouet at the mouth of the Penobscot River estuary in what is now Maine. This quickly became

an important revenue source for Plymouth Colony, rich in both fur and in the

increasingly important trade for timber, including all-important long, straight

logs for ship’s masts.

In 1635, however the French re-took the fort. Plymouth was determined to regain the plum and Standish was ordered to mount

an expedition.

This was a vastly larger enterprise than the local

raiding that he had led in the colony’s early years. It required a larger force—at least 30

militia men—and the chartering of an armed

merchantman whose crew could also supplement the attacking force. The plan was straight forward. The ship would sail into the bay and reduce

the palisade and earthwork fort by cannon fire, then land troops and take

the small garrison. There was no reason to doubt that this

would work.

Standish engaged the Good Hope, under Captain Girling. But when they arrived Girling, fearing the

Fort’s own guns, opened fire too far away to be effective and, ignoring

Standish’s pleas, continued to stand

off firing uselessly until

all of his shot and powder were expended. Standish had no choice but to abort the mission and return

to Plymouth. The failure of the Penobscot expedition was the biggest disappointment

of the Captain’s military career. It

also marked his last active combat

campaign.

The English finally regained the

post and the lucrative Penobscot trade 16 years later. It would change hands

several times more between the French, English, and Dutch before settling in

English hands along with French Canada

after the Seven Years War (French and

Indian War in North America). During the American Revolution Commodore Dudley Saltonstall and Colonel Paul Revere would be disgraced

after another, much larger Penobscot expedition ended in disaster.

The training at the next Militia

muster was conducted by Standish’s second in command, Lieutenant William Holmes. Two

years later, in 1637 as the largest military action the colony had yet mounted,

the Pequot War against the Pequot,

Narragansett, and Mohegans, and in an uneasy alliance with the Massachusetts Bay Colony,

Standish was ordered to raise and arm a company, which he dutifully

did. But Lt. Holmes commanded the men in

the field. At least in this way Standish

avoided association of his name with

some of the atrocities against the natives.

Although he continued to be annually

elected Captain of Militia until the end of his life, he was now an administrative and supervising officer rather than an active one.

| Myles Standish's grave site in the oldest still maintained cemetery of the English Colonists. |

Standish, 51 years old at the time of

his last campaign, turned his attention to his farm and large family. His oldest friend Hobbamock lived on the farm

with him until he died and was buried in the family plot. Standish lived

on, apparently a respected and happy man until he died of strangulation—probably kidney

disease—on October 3, 1656. He was

buried in a family plot in what is now known as the Myles Standish Burial Ground.

Despite his long association with

them, he never joined a Saints—we call them the Pilgrims—congregation for

reasons not very clear to historians.

His wife and children dutifully enrolled at First Parish Duxbury.

No comments:

Post a Comment