The 2023 Parliament of the World’s Religions flew largely under the radar of local media when it opened a packed agenda for the week at Chicago’s McCormick Place on Monday despite being the largest and widest international assembly of religions from every continent and faith tradition. It also has historic roots in one of the city’s seminal events—The World Columbian Exhibition of 1893.

Officially the seventh gathering since a centennial revival in 1993—the 2021 gathering had to be held on-line due to the global coronavirus pandemic—the theme this year is “A Call to Conscience: Defending Freedom & Human Rights.” It attracts participants from more than 200 diverse religious, indigenous, and secular beliefs from more than 80 nations. Among the dozens of important figures speaking or participating in panels are Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, Dharma Master Cheng Yen, Jane Goodall, Khaled Abu Awwad, Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi, Rev. James Lawson, Ojibwe Grandmother Mary Lyons, Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, Cardinal Blaise Cupich, Rabbi Hanan Schlesinger, Swami Yatidharmananda, and United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres.

Attendees at the Parliament of World's Religions in Salt Lake City, Utah in 2015.

The Parliament has been hosting a gathering of religious and spiritual leaders from all over the world and reflecting the vast diversity of beliefs and traditions practiced on this planet every roughly every five years since 1993. Previous Parliaments have convened in Chicago, Cape Town (1999), Barcelona (2004), Melbourne (2009), Salt Lake City (2015), and Toronto (2018). Each of these sessions has fostered inter-faith dialogue including finding common ground among communities often at violent odds with one another—Christianity/Islam/Judaism, Hindu/Islam. They have also raised recognition and respect for traditional native religions and “pagan” traditions. Co-operation on social justice, peacemaking, and climate change have been fostered. So has respect for the role of women in religion.

Delegates and speakers often tend to represent the most progressive elements in their traditions and those who are most willing to reach out to and learn from other traditions, even those with whom their communities have had strained or even violent histories. The fundamentalists of all traditions who assert that absolute truth and righteousness belongs to them only do not participate in the Parliament and despise those who do. Many participants face the threat of violence from within their own faith traditions as well as persecution by governments for their stands on human rights, the environment, and peace. Thus, some observers and much of the establishment press dismiss the Parliament as peripheral and irrelevant. Others see the seeds of mutual respect, understanding, and solidarity among the religious peoples of the world as essential for the survival of humanity and the planet we all share.

The modern Parliaments had their roots in a gathering held in conjunction with the World Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. The original World’s Parliament of Religions is now regarded along with guarantees of Religious Liberty set in motion by Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom and secured in the Third Amendment to the Constitution, and the Great Awakening as one of the most significant events in American religious history. It brought together for the first time world faith traditions, especially non-Christian ones on American soil, profoundly shaking an established consensus and opening a door to a whole new era.

A session of the 1893 World Parliament of Religion.

Believe me, it wasn’t easy.

The America of the late 19th Century was very different from the one we recognize today. Protestant Christianity, especially its Evangelical strain, exercised more cultural and political dominance over society than ever before despite the recent arrivals of waves of Catholic, Orthodox, and Jewish immigrants partly in response to fear of the new arrivals. The Deism and tolerance of many of the nation’s Founders and the hard fought-for rigid separation of church and state that had categorized the early years of the republic had crumbled. The light of the New England Renaissance and Transcendentalism had been swamped in successive waves of revivalism and isolated to an educated elite who the public was increasingly taught to scorn and despise. Dissenting sects or movements ranging from the Unitarians and Universalists to the Mormons and Spiritualists were increasingly isolated. Evangelical style and substance were growing within non-Evangelical traditions—the Episcopal Church, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and even some Quakers. It was influencing the immigrant waves of old Reformation Lutherans. Except in the biggest cities where their numbers were overwhelming, Jews and Catholics were excluded from political power and integration into the wider community.

There were flickers of resistance, of course. The revelations and implications of Darwin and other scientific advances sowed skepticism of traditional dogma among many. There was a resurgence of Free Thought as expounded by the likes of Robert Ingersoll. Every small town could be counted to have an iconoclast or two among its citizens. In part of the West a majority of the highly mobile population was unchurched and not unhappy about it. There may have been restlessness underneath the enforced consensus that was producing the morality mummery Anthony Comstock’s Society for the Suppression of Vice or the growing power and militancy of the prohibition movement, but few respectable people dared to speak up.

It was in this infertile time that an idea was hatched for a meeting of the world’s religions to be held during the World Columbian Exposition which was shaping up to be the largest and most spectacular of the international gatherings that were coming to be known as World’s Fairs. It was the brainchild of the Swedenborgian layman Judge Charles Carroll Bonney. The noted jurist had been appointed President of the World’s Congresses held during the Exposition. Eventually more than two hundred of these gatherings were scheduled each bringing together leaders in their fields including Congresses or Parliaments for anthropology, labor, medicine, temperance, commerce and finance, literature, history, art, philosophy, and science. Bonney thought that religion should also be included.

When he pitched the idea to leading Chicago churchmen he received an initial enthusiastic response until he made clear that the Parliament would include representatives on non-Christian faiths—heathens and pagans in many eyes. Others balked when they were told that they would not be allowed to evangelize or convert the delegates but would be required to treat them with dignity and respect—even those from “inferior races.”

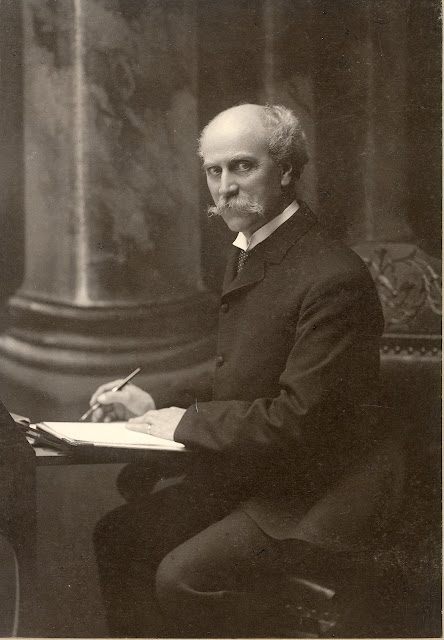

Rev. John Henry Barrows.

The Rev. Dr. John Henry Barrows, Minister of the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago and the city’s most respected clergyman agreed to be chairman of the Parliament. Barrows, the minister who claimed that Abraham Lincoln made a confession of faith to him in 1863—now regarded by most scholars with the greatest of skepticism—had subsequently become much more religiously liberal. He was sympathetic to the emerging social gospel movement in support of economic and social justice and had toured India and Japan and had a respectful interest in Oriental religion.

In 1891Barrow sent out thousands of invitations to religious leaders across the globe outlining his vision for a conference that would:

Bring together representatives of religions from all around the world.

Bring forth the truths the various religions teach in common.

Promote the brotherhood among the religious men of diverse faith.

In addition to acceptances, the invitations unleashed a firestorm of bitter attacks. Dwight Moody, Chicago’s fiery Evangelical leader led the local assault. The Archbishop of Canterbury wrote a scathing public denunciation, the European hierarchy of the Catholic Church—American Catholic Bishops were, as was customary in those days, keeping their heads down to avoid getting caught in the crossfire—, and the Ottoman Sultan all attacked the proceedings. Even Barrow’s own Presbyterian Church General Assembly, firmly in the hands of the denomination’s conservatives, denounced the project. None-the-less Barrows persevered.

Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones.

He enlisted as his top assistant and General Secretary the Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones who was the day-to-day administrator of the Parliament and in many ways the shaper of the final conference. Jones was a Civil War Veteran and a descendant of generations of Welsh Dissenters. He was the charismatic minister of All Souls Unitarian Church in Chicago and the long-time Secretary of the Western Unitarian Conference, the semi-independent Unitarian body which promoted a radical and non-doctrinal faith. He was a strong supporter of the Social Gospel movement and through his Unity Clubs and Unity Magazine promoted dialogue with and respect for Freethinkers and emerging Humanism. Jones’s theological and political radicalism further alienated conservatives. But he had strong connections in the city and quiet support from many wealthy men who were prevailed upon to financially support the Parliament.

The Parliament finally convened at the Hall of Columbus, now the Art Institute building on Michigan Avenue, on September 11, 1893 with over 4,000 in attendance. From the beginning the press was enchanted by the colorful pageantry of the assembled delegations. Although Protestant Christians still dominated the attendees and slated speakers, it was the exotics that drew the most attention.

It was the first time most Americans were ever exposed to most non-western religions. There were 12 Buddhist speakers including Soyen Shaku, the first Japanese Zen master to come to the U.S. whose translated speech was read to the delegates by Dr. Barrows and Anagarika Dharmapala, a leading Sri Lankan monk and representative of Southern or Theravāda Buddhism.

Swami Vivekananda, star of the 1893 Parliament.

Among several Hindus in attendance was the breakout star of the whole conference, Swami Vivekananda who spoke briefly on the opening day of the sessions. His opening words, “Sisters and brothers of America!” caused the assembly to break into a wild two minute long standing ovation. He made two more formal addresses to the Parliament and spoke dozens of other times at smaller sessions, private gatherings, and even in the parlors of wealthy Chicagoans. Although Ralph Waldo Emerson had been heavily influenced by a translation of the Bhagavad Gita in his essay The Over-Soul, Americans at the time were almost entirely ignorant of Hinduism. But they were greatly taken by Vivekanada’s repeated messages of religious universality and toleration which summed up the aspirations of the whole Parliament. His first short address referenced two quotes from the Shiva Mahimna Stotram:

As the different streams having their sources in different places all mingle their water in the sea, so, O Lord, the different paths which men take, through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee!.. Whosoever comes to Me, through whatsoever form, I reach him; all men are struggling through paths that in the end lead to Me.

Swami Vivekananda remained in North America for two more years touring and speaking extensively. A collection of his writings became a best seller. He established the Vedanta Society as a ministry to the West which adapted traditional Hindu teaching to Western culture and needs and which helped introduce the practice of yoga.

Eleven speakers represented Judaism including traditional rabbis and more secularized Jews. Opposition from the Sultan hindered a major participation by Muslims. There were just two representatives, and the main speaker was the American convert Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb. There were also Parsi, Confucian, Shinto, Tao, and Jain representatives.

The Parliament also recognized and presented the views of new religious movements of the time, including Spiritualism and Christian Science. Newly emerging Baha’i was referenced in an address by the Rev. Henry Jessup, a Presbyterian minister who was a leading orientalist and founder of the Syrian Protestant College, now known as the American University of Beirut.

Eleven women including ordained ministers spoke at the Parliament, something that shocked the sensibilities of even some of its supporters. So did African-American Christians, but no spokesmen for the traditional religions of Africa. Neither Native American nor any other aboriginal people were invited due to the Parliament’s express aims of seeking commonality among the “10 Great World Religions.”

When the Parliament ended after seventeen days, it was widely hailed as a success. Religious toleration, an appreciation for certain common threads that were seen to run through all of the represented religions, and the need to promote study of comparative religion in American colleges and seminaries all got a boost. So did the more liberal strands of Protestantism, although it also pushed conservatives to the creation of modern Christian Fundamentalism in the early 20th Century in reaction. Interest in Eastern religion was sparked and in coming years a parade of yogis, gurus, and Buddhist masters would follow in Swami Vivekananda’s footsteps and establish American followings.

Jews and even Catholics, who had largely boycotted the Parliament benefited from the encouragement for toleration that the Parliament promoted and the brotherhood of man movement in the coming years.

Jenkin Lloyd Jones spent the rest of his life processing his experiences at the Parliament and writing about them in his books A Chorus of Faith, Seven Great Religious Teachers, and A Seven Years Course in Religion. American Unitarianism was profoundly shaken. The Eastern leadership of the American Unitarian Association and the General Conference of Unitarian Churches had both been drifting toward bringing Unitarianism back into the fold of respectable Christian Denominations, but the Parliament strengthened the independent streak represented by the Western Conference and encouraged the hand of non-creedalists everywhere.

The Universalists, who were marginally involved, were even more profoundly moved. The idea that if God redeemed all souls, it was not necessary to do so through the agency of Christ or any particular set of religious beliefs took root. Within a couple of generations Universalism would be even more post-Christian than the Unitarians. They would come to view all religions as a path to union with God or something Greater.

Pope Francis has expressed a kind of small u universalism as have other world religious leaders including the Dalai Lama, the late Archbishop Tutu, and Buddhist Monk Thích Nhất Hạnh.

Liberal, or mainstream protestants would on take a more modified and limited universalism with a small u. And recently Pope Francis has echoed similar sentiments and has been charged with deserting Catholic doctrine for reckless universalism.

And so it goes…thanks to the first World Parliament of Religion.

No comments:

Post a Comment