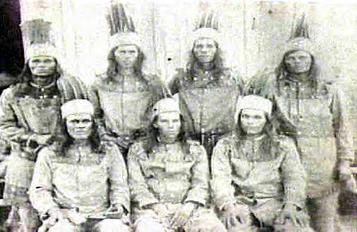

Lumbee tribe members surround a Ku Klux Klan rally meant to intimidate them in rural North Carolina.

The area around Maxton, North Carolina was not typical of the Deep South in the 1950's when Jim Crow law were beginning to be challenged by the emerging Civil Rights Movement. The population split between Whites, African-Americans, and a distinct Native American tribe included members also descended from the other two races. They had lived side by side if not together, and not without difficulties, but on the whole amicably for more than 200 years.

The region, tucked away by the South Carolina border, was divided by Robeson and Scotland Counties where the Coastal Plane begins to fade into the Piedmont. Settlements there by mostly Scottish colonists as early as 1775 identified four villages or clans of Siouian-speaking communities. The people began to call themselves Lumbee for the Lumber River that flowed through their hunting grounds. During the American Revolution both Anglos and natives enlisted, mostly in the State Militia. So did sizable numbers of Free Blacks. Pension records show that several members of known Lumbee families were listed as Free Blacks, evidence of intermarriage.

Robeson and Scotland Counties by the South Carolina border right where it takes it turn due west.

In the late 18th Century Lumbee families began buying land, obtaining it as a veteran grant, and gaining, for the first time, legal ownership of traditional land. Several families amassed substantial holdings and some owned slaves. But the isolated area away from major river routes did not lend itself to large scale plantation system farming. Most families in all groups were small, subsistence farmers, seasonal hunters, and hired laborers.

Isolation was good for the tribe. They were not swept up by Andrew Jackson's Indian Removal policy. In fact they were the largest remaining group north of Florida. In the late 1830s and '40s they welcomed and absorbed Iroquoian speaking Tuscarora groups likewise stranded when the rest of their people were exiled west of the Mississippi.

None-the-less when the State of North Carolina began adopting and enforcing Free Black Codes, the Lumbee were stripped of the citizenship rights they had long enjoyed including the rights to vote, purchase property, serve on a Jury, muster with the militia, or posses fire arms. The enforcement of the fire arms ban was particularly galling because hunting was an important part of feeding their families. Several prominent men were arrested, tried, and punished.

Like many small, non-slaveholders some local Whites and Natives resented the haughty Tidewater aristocracy that drove secession and Civil War. Some were avowed Unionists or sympathizers and avoided Confederate Service and war taxes. When the South enacted a draft, some fled into the woods and back country including those sheltered by the Lumbee.

Other members of the tribe, however, remained loyal to their state and the Confederacy and served in the war. Northern forces never came near the remote area. But after the war most Lumbee supported Democrats because they resented the Reconstruction 40 Acres and a Mule for Freemen but did not include those living as members of the tribe. In fact, the Federal government refused to recognize them as a tribe.

Under Republican control the State set up separate school for Whites and Blacks. As non-whites were excluded from white schools and compelled to attend Freedman schools. They began to campaign for their own schools.

They renamed the central market town originally named Shoe Hill to Tilden in honor of the Democratic Presidential Candidate who promised to end Federal occupation in the South. Tilden won the popular vote but the election was among the most contentious in American history, and was only resolved by the Compromise of 1877 in which Republican Rutherford B. Hayes agreed to end Reconstruction in exchange for recognition of his presidency. Without Federal troops, Democrats quickly regained control of Southern governments and began enacting the Jim Crow laws that returned Blacks semi-servitude with no Civil Rights.

Men of the extended Lumbee Chavis family in traditional dress in the Post Civil War Era. In their daily lives tribal members wore the same ordinary work clothing as their White neighbors, lived on their own farms, used Anglo style names, and commonly spoke.As part of a reward for Lumbee support, Democrats began to look for ways to created Native schools. To do that they needed to officially recognize the tribe. In the 1880s, as the Democratic Party was struggling against a biracial Populist movement which combined poor Whites both Populist and Democrats and Blacks Republicans the state recognized the Indian people of Robeson County as the Croatan Indians and to create a separate system of Croatan Indian schools. Croatan referred to the once powerful native confederation around Roanoke in the earliest days of colonization. There was no known connection between the Lumbee and that nation. By the end of the 19th century, they were legally known as Indians of Robeson County and had established schools in eleven of their principal settlements. The town of Tilden was finally renamed Maxton.

The Lumbee and their Democratic Party allies in Congress campaigned unsuccessfully for decades in the 20th Century for Federal recognition as a tribe primarily to get support for their schools. Repeatedly rebuffed they resorted to petitioning under the names Croaton Cherokee and later Croaton as Siouans to take advantage of those Western tribes' existing recognition. They had no real connection to the Eastern Band of Cherokee in South Carolina who vigorously protested their claim and dim 200 year old connections to the Sioux. Both claims were ignored.

The Croatan Normal School at Pembroke, North Carolina, 1916, the first Croatan (Lumbee) Indian school established and supported by the state.In 1919 an agent of the Indian Office reported:

While these Indians are essentially an agricultural people, I believe them to be as capable of learning the mechanical trades as the average white youth. The foregoing facts suggest the character of the educational institution that should be established for them, in case Congress sees fit to make the necessary appropriation, namely the establishment of an agricultural and mechanical school, in which domestic science shall also be taught.

Then in 1934 another agent reported:

I find that the sense of racial solidarity is growing stronger and that the members of this tribe are cooperating more and more with each other with the object in view of promoting the mutual benefit of all the members. It is clear to my mind that sooner of later government action will have to be taken in the name of justice and humanity to aid them.

World War II put efforts for Federal recognition on hold while tribal members, like their White and Black neighbors, went into the service. Near full domestic employment brought unheard of prosperity as other members left to work in defense industries in regional cities. And when it was over returning GIs used their benefits to buy new homes, start small businesses, and attend college. Although still poorer than the rest of the country, by 1950 most members were living in homes with electricity, running water, and telephones as well as owning a family car or truck. Everyone had modern shot guns and varmint rifles for hunting--and self-defense. That was resented by some whites who thought the native veterans were "uppity" and disrespectful.

In the immediate post-war years the bid for Federal recognition was put on hold during an internal dispute over what tribal name to request with factions favoring Croaton, Cherokee-Coaton, or Cheraw [Souian]. What they agreed on was that they no longer wanted to be designated the Indians of Robeson County anymore, especially since their populations was spread far beyond that limited jurisdiction.

In the early 1950s, Reverend D. F. Lowry organized the Lumbee Brotherhood. Lowry and his supporters contended that since their people were most likely the descendants of a mixture of colonial-era indigenous tribes—a theory many scholars supported—they should adopt the name Lumbee after the river that had become the cultural heart of the community. In 1952 members overwhelmingly voted to adopt the new name, and the North Carolina General Assembly changed their official designation in 1953 to the Lumbees. That paved the way for Congressional action at last.

The Lumbee Act passed by Congress in late May 1956 as a concession to political lobbying and signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower designated the Lumbee as an Indian people. It withheld full recognition as a "Tribe", as had been agreed to by the Lumbee leaders. The Lumbee Act designated the Indians of Robeson, Hoke, Scotland, and Cumberland Counties as the Lumbee Indians of North Carolina. But there was a catch. The Act stipulated, "Nothing in this Act shall make such Indians eligible for any services performed by the United States for Indians because of their status as Indians." It also forbad a Government relationship with the Lumbee and banned them from applying through the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) administrative process to gain recognition.

The rational was The Lumbee had essentially assimilated into early colonial life prior to the formation of the United States. They lived as individuals, as did any other colonial and U.S. citizens. Lumbee spokesmen repeatedly testified at these hearings that they were not seeking federal financial benefits; they said they only wanted a name designation as Lumbee people.

The Blood Drop Cross logo used by the Ku Klux Klan represented the the "one drop rule" what classified any one with "even a single drop" of Black or Native blood could taint someone "passing" for White. The multi-racial Lumbee were a prime example of that threat.The fight for tribal identity put them in the spotlight, especially because tribal members were descended from Native, White, and Black individuals and there was still inter-racial marriage. Playing on racial anxiety and resentment of Lumbee competition for jobs and property Grand Dragon of the Kights of the Ku Klux began a campaign of harassment against the Lumbee, as mongrels and half-breeds whose race mixing threatened to upset the established order of the Jim Crow South. After giving a series of speeches denouncing the loose morals of Lumbee women, Cole burned a cross in the front yard of a Lumbee woman in St. Pauls as a warning.

The Civil Rights Movement was gaining strength across the former Confederate states--the Brown v Board of Education Supreme Court decision had just made segregated public schools illegal and Whites were turning to the once-again revived KKK. Cole thought that an attack on the Lumbee would be easy pickings and a recruitment tool in North Carolina where Klan growth lagged behind neighboring states. He called for a Klan rally on January 18, 1958, near the Maxton.

The Lumbee, led by veterans of World War II and Korea, decided to disrupt the rally.

Cole had predicted more than 5,000 Klansmen would show up for the rally, but that night fewer than 100 and possibly as few as three dozen attended. Klansmen had prepared for the rally in a large field, with loudspeakers, a cross to be burned, and a large banner. Cole, who was from South Carolina, misunderstood the racial dynamics in Lumbee territory including relatively good relations with local Whites and the extent to which the tribe was prepared to defend itself and other indigenous people.

More than 500 Lumbee, armed with guns, sticks, and ax handles gathered in a nearby swamp. When they realized they possessed an overwhelming numerical advantage, they attacked the Klansmen encircling the Klansmen, opening fire and wounding four in the first volley, none seriously.

Local newspaper headlines expressed astonishment at the rout of the Klan.Local law enforcement showed up after the altercation had taken place, but by then, the field was clear. It turned out that the long tribal support of Democrats and friendly ties with local authorities paid off. The remaining Klansmen panicked and fled. Cole was found in the swamps, arrested and tried for inciting a riot.

The Lumbees gathered up discarded robes and the rally banner and marched back into Maxton to celebrate, which included burning Catfish Cole in effigy. Press coverage showcased two Lumbee men, one a celebrated World War II bomber engineer, wrapped in the KKK banner they had torn off a Klansmen’s car at the rally.

Simon Oxedine and Charlie Warriax, decorated WWII veterans, displaying their captured KKK flag at a Veterans of Foreign Wars convention.The Lumbee celebrated the victory by burning Klan regalia and dancing around the open flames.

The Battle of Hayes Pond, or the Klan Run, as it came to be called, marked the end of Klan activity in Robeson County, is still celebrated as a Lumbee holiday.

No comments:

Post a Comment