|

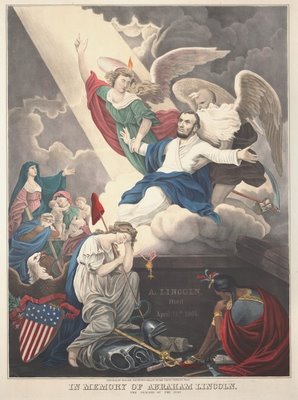

| One of the spurious quotes often used by Evangelicals and the Religious Right to claim Lincoln. |

Note: I

know it’s been a week with a lot of retreads.

The difference is that today’s actually has requests! My look back at Abraham Lincoln’s complex but

not unfathomable religious life and identity continues to resonate with some

readers. One thing has changed since the

first version appeared—the Republicans have completed their total inversion

from the party that rose to power with the Great Emancipator. Now fully embracing, even reveling in the

Confederate flag and values, xenophobia, bloodthirsty war glorification, and

rejection of any semblance of sympathy or compassion, the new GOP hardly even

bothers to nod in Abe’s direction anymore.

Meanwhile religious liberals find much to admire but have a hard time

nailing the entrails of his beliefs to the barn door.

Back in 2009 the nation was in the grip of a wave of Lincoln mania in

conjunction with the bi-centennial of

his birth. There was an avalanche of new books and

articles examining every aspect of

the Great Emancipator’s life, work, and connections.

The Religious Right—those who were not also neo-Confederates anyway—was busy, as usual, trying to retroactively adopt him as an Evangelical Christian. On the other hand the small world of the Unitarian Universalist blog-o-sphere and

a spate of sermons, tried to lay

claims that Lincoln was, at least in spirit, a Unitarian or a Universalist.

Scott

Wells, a leading Universalist and

Christian blogger from a Southern background claimed to be immune to the cult of Lincoln worship. For

his family Lincoln represented oppression, destruction, and, for them, the nightmare of Reconstruction. He also

scolded U.U.s for trying to appropriate

Lincoln into our ever popular lists

of famous UUs.

The following is adapted from my response to Wells.

Hagiography aside, there are many reasons to put your understandable regional bias aside and

spend some time studying Abraham Lincoln. As flawed

and inconsistent as any man, he is

still rewarding for the subtlety and depth of his thought and

his life-long struggle to reconcile a true and deeply held idealism with both personal ambition and the need

to act in a brutal and unforgiving environment. Even Harry Truman, a Missouri Democrat whose unreconstructed

Confederate mother never forgave him for making Lincoln’s Birthday a national holiday, came to deeply admire

his ancient tribal enemy.

| |

| When Lincoln was asked about his as his religion. |

Lincoln’s relationships to religion are not a murky as some suppose.

Certainly any denomination that

would attempt to claim him as its own

is self-delusional. Here is some of

what we know.

1) At no time in Lincoln’s life did he ever claim to be a Christian as understood in

his time or to be saved.

2)

As far is known he was never baptized

and never became a member of any

church.

3)

Among his earliest published

writings were attacks on a political rival,

Peter Cartwright, a fire-and-brimstone Methodist circuit rider

who had accused Lincoln of infidelity

and had used his wide Methodist connections

to build a Democratic political operation. The articles, which appeared under a nom

de plume, mocked both the man’s religion and his

attempts to use his followers as a political base. Lincoln claimed never to have “denied the

truth of Scripture” but did

acknowledge that he was not a church member.

Lincoln defeated Cartwright

for a seat in Congress, but

Cartwright’s charges that he was an infidel—and

his own tart responses—would dog him for years.

4)

Like most self-educated

Americans who had literary aspirations

and who were not versed in the Latin and Greek of the Eastern college

educated elite, Lincoln had two primary

sources to draw from for both inspiration

and style—The King James Version of the Bible and the popular plays of William Shakespeare.

He knew both. But his writing was infused with the cadences

and majesty of the Bible. He could also, if the occasion

called for it, usually in response to some hypocrisy

from the mouth of a believer, quote verse with ease.

5)

He deeply admired Thomas

Jefferson and treasured the Declaration

of Independence as the essential founding

document. He borrowed from Jefferson, and from George Washington, the language of Deism in public discourse.

He frequently spoke of Providence, Creator, and other Deist constructions.

He did not avoid the word God as they usually did, but he did not

invoke an explicitly Christian God.

One can search in vain for much use

of the words Christ or Savior outside of the context of letters of condolence to the families

of fallen soldiers often echoing

back sentiments expressed by the bereaved.

He was all for giving whatever comfort

he could.

6) In Springfield he attended Mary’s

Presbyterian Church and was friendly

with its minister but never joined

the church or partook in the Spartan Presbyterian communion. That hasn’t stopped that congregation from

calling itself “Lincoln’s Church” to

this day.

7) He read the published sermons of both William

Ellery Channing and Theodore Parker

and appropriated or adapted words from each—especially

Parker—in his speeches. But in practice as President, despite a personally cordial relationship with Radical Republican Senator Charles Sumner, he found Abolitionist Unitarians

to be pig-headed impediments to a practical prosecution of the war and a

move toward healing a post-war, re-united country. Despite

this the UU congregation in

Springfield proudly adopted his

name.

8) He believed deeply and viscerally

in Fate and implacable Destiny. This was part

and parcel of his widely reported melancholia.

Some scholars have attributed this to a sort of Calvinist hang-over.

Could be. But Lincoln’s sense of fate and destiny seem to rise from far more ancient impulses.

9) There is nothing to connect

Lincoln to institutional Universalism.

Steven Rowe at A Southern Universalist Church

History responded to Wells with an excerpt

from memoirs by Universalist minister quoting an appreciative

comment by Lincoln:

“I used

to think that it took the smartest kind of man to preach and defend

Universalism; I now think entirely different. It is the easiest faith to preach

that I have ever heard. There is more

proof in its favor, than in any other doctrine I have ever heard. I have a suit in court here to-morrow and if I

had as much proof in its favor as there is in Universalism, I would go home,

and leave my student to take charge of it, and I should feel perfectly certain

that he would gain it.”

Unfortunately there are no other witnesses to Lincoln attending the debate described or speaking this assessment of it. And I am

sure a diligent search of the

memoirs of ministers of other denominations can turn up appreciative Lincoln

quotes, some perhaps true, others the product

of devout wishful thinking. Yet

there is much to suggest that Lincoln privately embraced a kind universalism of spirit that accepted a common struggle for understanding a greater mystery that transcended mere denominationalism.

10) In the White House, with the gruesome

burdens of a war-time presidency

on his shoulders and the private grief over the loss of his beloved son Willie, Lincoln

followed Mary’s lead and seemed to take Spiritualism,

then at the height of its American popularity, with due seriousness. At the time many

Universalist ministers were also toying—to

considerable controversy—with Spiritualism. But again Lincoln never publicly endorsed Spiritualism, or

acknowledged it as his faith.

|

| Lincoln's head replaced Washington's in this allegorical apotheosis print, part of the rapid sanctification of the martyred President after the war. |

In the post-war years both the

Abolitionist preachers with whom he sparred during the war and a generation of new Unitarian leaders bloodied on the battlefields of that war—Jenkin

Lloyd Jones being a prime example—participated in the myth making that turned the martyred President into a kind of a Saint. They went too far. And rubbing the defeated

South’s nose in it exacerbated

the regional disdain with which

continues to deepen.

But I think many modern Unitarians

and Universalists can find much with which to resonate in Lincoln’s personal

spiritual journey. It so resembles so many of our own.

No comments:

Post a Comment