|

| Union Pacific and Central Pacific tracks meet at Promontory Point, Utah. |

On

May 10, 1869 the United States was

bound together as never before when the final Golden Spike was driven at Promontory

Point in Utah connecting the Union Pacific Railroad (U.P) from the

east with the Central Pacific (C.P.)from

California. Together the two

railroads formed the first Transcontinental

rail connection.

Construction was spurred by

the Civil War and the Union’s need to connect to California and its gold

wealth to help finance the war. The construction was authorized and encouraged by

the Railroad Acts of 1862 and 1864 which provided financing for the enormously expensive undertaking through 30 year bonds and extensive

land grants to the railroad companies along their rights of way.

Competition was encouraged

by tying the land grants to track

actually laid. The Central Pacific

got started first in 1863 heading east out of Sacramento and employed thousands of Chinese emigrant “Coolie”

labor for most of the grueling and dangerous pick-and-shovel work. The western railroad was challenged by the

daunting Sierra Nevada Mountains. Workers hahd to construct steep mountain-side grades and switchbacks

and bore long tunnels through hard rock. Unstable nitro-glycerin

was used for blasting resulting

in many deaths and horrible injuries. Naturally progress on the west end was

slow.

|

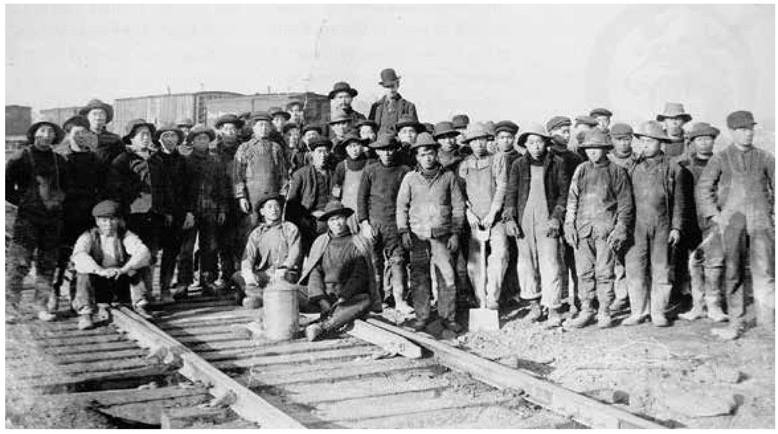

| This gang of Chinese laborers on the CP, taken nearly a decade after the brutal drive through the Sierras, was far beter clad for winter work than the coolies first employed. |

Construction

on the Union Pacific ironically was held up by manpower and material

shortages due to the war. It did not

start in earnest until the war was over.

The railroad was under the control of Thomas Clark Durant, a crook

and charlatan with good political connections—he had hired

Illinois lawyer Abraham Lincoln for some lucrative pre-war railroad business.

In

point of fact Omaha, across the Missouri River from the official

terminus at Council Bluffs, Iowa was

the actual jumping off point because no bridge was yet built across

the river. In two and a half years

since 1863 construction had only gotten 40 miles west of the river as Durant ate up daily government subsidies, directed

the line in an illogical course to

connect with his land speculations,

and built numerous useless “ox-bows”

to gobble up more grant land.

In

addition he contracted with Crédit

Mobilier, a construction company he secretly

owned, and skimmed profits all

the while bribing members of Congress to look the other way. All of that would blow up into an enormous scandal in the next decade.

In

the mean time the likelihood of at least some direct Federal oversight of the project caused a new beginning in July

1869 with Durant’s war time collaborator in a scheme to deal in contraband Confederate cotton, General Grenville Dodge, in

charge. At least Dodge proved to be a competent manager. The line started driving west, rapidly laying

track over the open plains of Nebraska.

| General Grenville Dodge was marginally less corrupt than Thomas Clark Durant and the competent, efficient, ruthless construction boss on the UP. |

The

eastern crews were largely Irish emigrant

“navies” and rootless veterans of both the Union and Confederate armies. They

were a volatile bunch. Often paid

in script that could only be redeemed

at the end of track towns known

collectively as Hell on Wheels, they drank up their earnings

and brawled incessantly. They were also apt to stage numerous strikes and job actions. Still, crossing

such relatively good ground they were gobbling

up miles—and enriching the U.P.’s land grants at an astonishing rate.

Accompanying,

and working slightly ahead of both lines were the telegraph wires that hummed with

construction business. Communications in

the gap between the two railroads

and their telegraphs was the job of the short

lived Pony Express.

The

U.P. began encountering harassment

and attacks by Native Americans who recognized that the line was a threat to their way of life. Numerous attacks somewhat slowed

construction, which required U.S. Army protection.

| Native American tribes recognized the threat to their way of life represented by the railroad. |

The

vast buffalo herds roaming the land

also presented a threat to construction—and an endless supply of cheap meat for the labors. The railroad employed hunters like William F. Cody

(Buffalo Bill) and James Butler

Hickok (Wild Bill) to slaughter

the animals by the thousands starting the eradication

of the great herds that would be almost complete within a decade.

Meanwhile

the C.P finally broke through the mountains and into the high desert of Nevada and was able to launch its own

race to the east. Unfortunately for the

C.P. the lands it was earning were not much suitable for sale or settlement—although

they would later yield a wealth of

minerals.

When

the U.P. entered Utah, Brigham Young

contracted hundred of Mormon laborers

to the railroad. These tea-totaling workers disciplined by

their own church leaders ended much of the labor turmoil on the line.

It

was determined to run the line north of The

Great Salt Lake rather than try to cross that shallow body by trestle. The route missed the Mormon capital of Salt Lake City, but Young was cut

in for rights to build a feeder line.

When

the two lines met just north of the lake at Promontory Point, the U.P. had laid

1,087 miles of track and the C.P. 690

hard won miles.

California Governor Leland Stanford, himself one of

the Big Four investors in the C.P., came for the ceremonial joining. Dodge and a host of Eastern politicians were also on hand. Stanford was given the privilege of driving

the final Golden Spike, which was wired

to a telegraph line to send a signal

across the nation that the job was complete.

Overnight

traveling time between Omaha and California by wagon was cut from six to eight grueling, dangerous months to six

days in an uncomfortable but relatively safe railroad passenger car. The train could also accommodate all of the household goods, farm equipment, stock,

and supplies that were often destroyed, abandoned, or used up on

the long wagon trek. And suddenly news from San Francisco could reach London

all of the European capitals via

Western Union and the Transatlantic Cable virtually

instantaneously.

Despite

the hook up, final connections on

both ends to make for continuous rail service from coast-to-coast were not complete. It wasn’t until November that the C.P.

completed its link west from Sacramento to Alameda

on the shores of San Francisco

Bay. And passengers and freight cars

still had to be ferried over the

Missouri River until Durant finally got around to building a bridge in 1872.

By

the time the last spike was driven, construction had begun on southern and northern transcontinental lines and on numerous feeder and connector

lines. Just twenty one years after

the completion of the line, West was largely

settled and the Census Bureau officially declared an end to the American Frontier.

|

| The Hell on Wheels tent city along what would become 16th street in Cheyenne near Crow Creek in 1867. |

On

a personal note, my home town of Cheyenne, Wyoming began as just another

Hell on Wheels. Its location about half

way between Omaha and the Great Salt Lake made it the ideal spot for a U.P. division point, and for major maintenance shops and humping yards to make up trains to cross the mountains. Located due north of Denver, which had been bypassed, it was also the natural location

for a feeder line which eventually became part of the Burlington Northern system.

The Cheyenne of my youth was always a railroad town—a U.P. town—and knew

it.

No comments:

Post a Comment