| Victoria Woodhull in her prime. |

Victoria

Claflin Woodhull was nominated for President of the United

States on April 10, 1872 almost 50 years before the passage of the 19th

Amendment gave women the right to vote in all of the United

States. Woodhull stood apart from

other leaders of the Suffrage movement by her audacity, frank

embrace of the most radical social causes, her shocking open

challenge to Victorian sexual mores, and her mesmerizing

affect on the public and press.

As early as 1870 Woodhull used the pages of Horace Greeley’s New York Herald to announce her

candidacy for President in the 1872 election.

It was a bold move. Not

only were women barred from the vote, but she would not even reach the constitutionally

mandated age of 35 until months after the March 1873 inauguration of

the next President. She maintained that

while the law forbad women from voting, there was not a statutory ban

on women running for, or being elected to office. In the hubbub created by her

announcement over the unprecedented distaff candidacy, her age never

became an issue.

She used the pages of her newspaper, Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly which was founded the

same year, and the lecture platform to keep her name and promised candidacy

before the public. Able to command press

attention, which then as now liked a sexy and sensational show,

she attracted the support of not only the most daring womanists and suffrage

supporters, but radical trade unionists, early socialists, prison

and death sentence reformers, some former abolitionists, and free

thinkers. She took on a broad range

of social issues and took a consistently radical and progressive

stance.

On May 10, 1872 a meeting was held at Apollo Hall in New York

City where the new Equal Rights Party was formed and

announced its intentions to nominate Woodhull.

The meeting consisted almost entirely of Woodhull’s friends and inner

circle of supporters. A formal convention was called and

held on June 8 with broader participation.

A platform was announced, personally drafted by

Woodhull, and her personal friend, the great Black abolitionist Fredrick

Douglas was nominated for vice president. Douglas, however, was not present at the

Convention and never acknowledged or accepted the nomination

although he never officially renounced it. In fact that fall he would be elected as a Republican

New York Presidential Elector.

The issue of Woodhull and Claflin’s

Weekly dated the same day as the Convention announced the ticket and

platform:

The Equal Rights Party has selected Victoria C. Woodhull for the office of

President, because it deems that the demand for the personal, social, legal,

and political liberties of woman have been better advocated by her actions and

in her speeches and writings than by any other woman. Religious liberty is not

mentioned above, because it is held that, in the case of woman, it has not been

specially infringed. It is claimed as a

right pertaining to all the people; one which the Equal Rights Party hold

itself pledged to maintain against any national or State interference with (or

infringement of) in any way whatever.

The Equal Rights Party has selected Frederick Douglass for the office of

Vice President, because though born a slave, he has himself achieved both his

education and his liberty; because he has waged a life-long, manful battle for

the rights of his race, in which those of mankind were included; because he has

proved that he knows how to assert the liberties of the people, and

consequently it is assumed that he knows how to maintain them.

This announcement and its tone of radical defiance was picked up by the

press across the country. And all

hell soon broke loose. The candidate

was in for a very bumpy ride.

Woodhull was born in Homer, Ohio on September 23 1838, the daughter

of a ne’er-do-well con artist and patent medicine peddler who

may have passed on some of his persuasive flair to his beautiful

older daughter.

At the age of 15 she married a 28 year old doctor—and perhaps a quack—Canning

Woodhull. The couple had two

children including a boy with an “intellectual disability.” Victoria

soon discovered that her husband was an alcoholic, a chronic

womanizer, and was abusive. Unable,

or unwilling, to support the family, he relied on his wife to provide

income. In San Francisco she

worked as a cigar girl in rough and tumble saloons, and

likely at least occasionally as a prostitute.

Later in New York she began her long collaboration with her

younger sister Tennessee Claflin presenting themselves as clairvoyants

and spiritual healers. When her husband

essentially abandoned the family, the sisters successfully took their

act to Cincinnati and Chicago and began touring as spiritualist

lecturers. After 11 years Victoria obtained

a divorce from her husband.

Her experience would inform her public rejection of conventional

marriage as a form of chattel slavery for women. She became attracted to the Free Love movement

that percolated on the very most advanced frontiers of Free Thinking. Around 1866 she either married or took up

a common law relationship with Col. James Blood, a kind

and cultured gentleman who subscribed to Free Love.

They settled back in New York with sister Tennessee and her extended

family. Living in relative comfort

and respectability, the sisters established a popular salon where

advanced thinkers and practical politicians rubbed shoulders. Among her admirers was Benjamin Butler,

the Radical Republican politician and former general who espoused

both suffrage for women and free love.

Virginia proved a brilliant and daring conversationalist and

advocated by turns and in combinations anarchism, socialism, Spiritualism,

and racial equality.

|

| A popular men's sporting and gossip newspaper--a competitor of the Police Gazzette, found the Woodhull and Claflin Brokrage house a topic of amusement. |

Sister Tennessee caught the fancy of 76 year old Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, who

took her for a lover, consulted with her for spiritual advice

and returned the favor by offering

inside stock tips. Armed with such

information, the sisters invested

and reaped fabulous profits. Vanderbilt helped set them up in the first

woman owned brokerage firm on Wall

Street, Woodhull, Claflin & Company.

The press hailed them as Queens

of Finance. Susan B. Anthony regarded the venture as “a new phase of the

woman’s rights question.” Victoria, with

typical blunt frankness noted that,

“Woman’s ability to earn money is better protection against the tyranny and

brutality of men than her ability to vote.”

In 1870 the sisters took advantage of their fame by launching their own

weekly newspaper, Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly. Victoria was the principle editor and writer.

The paper took on and advanced all of the most progressive causes of its

day. But it also pioneered in muckraking and

investigative journalism, exposing fraudulent stock schemes, insurance frauds, and shady Congressional land deals.

The newspaper, which was often sold

under the counter and was sometimes banned

from the mails, had a very respectable circulation of more than 20,000

copies weekly for most of its seven year run.

In January 1871 Woodhull personally

petitioned Congress on behalf of

women’s suffrage. She argued that the

recently enacted 13th and 14th Amendments extended to women the same

rights as newly freed slaves. Her argument attracted wide attention and admiration. Although a majority report rejected her assertions,

Benjamin Butler filed a minority report

in her favor. Leaders of the Suffrage

movement including Anthony, Lucretia

Mott, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton

invited her to address a meeting of

the National Women Suffrage Association

(NWSA) the next day.

But the spotlight

of the Presidential campaign was thrown soon

thrown on Woodhull’s most unusual

household, which included not only her present

husband, but also her first who had shown up penniless and addicted to

morphine and was taken in out of

charity; her sisters and their liaisons;

and her parents including the father who still was running patent medicine

scams. When her mother tried to blackmail

Vanderbilt posing as Tennessee, he

naturally withdrew his support and advice and

turned his significant power against the sisters, who were soon forced out of their mansion ending

their Salon.

Woodhull simply replaced the money lost from her

business with speaking fees.

The powerful Beecher

family, evangelist Henry Ward

and his sisters Harriet Beecher Stowe and

Catherine began a concerted campaign against Woodhull for

her advocacy of Free Love. A third

sister, Isabella Beecher Hooker, a

leader in the NWSA, supported her.

Woodhull became aware that Henry Ward was carrying on an adulterous affair with

the wife of an associate. She attempted to use that knowledge to get

the Reverend not only to back off his

attacks, but to introduce her at

a major public lecture at Steinway Hall. Despite the thinly veiled blackmail

attempt, Beecher backed out at the last moment and Woodhull was introduced by Theodore Tilton, the cuckolded husband of Beecher’s

lover.

The speech itself went well until Woodhull’s younger

sister Utica, bitter over Victoria’s

fame and notoriety stood up in a box

and directly challenged her sister

to publicly proclaim her support of free love.

“Yes, I

am a free lover!” Woodhull defiantly

retorted, “I have an unalienable, constitutional, and natural

right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can, to

change that love every day if I please! And with the right neither you nor any

law you can frame have any right to interfere.”

|

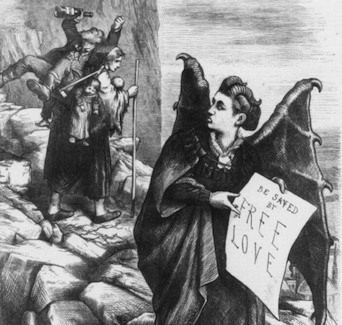

| Woodhull was depicted as Satan for her advocacy of Free Love. |

The subsequent

scandal rocked the country and split

the suffrage movement. None the less

the NWSA stood by her and even recommended nominated her for President with Fredrick Douglas for Vice President in

January of 1872.

Woodhull ran against Republican incumbent Ulysses

S. Grant and the Democratic nominee,

famed maverick editor and publisher Horace Greeley, a former liberal Republican and erstwhile ally. Victoria attempted to concentrate her

campaign on the highly progressive Woodhull

Platform. But her now considerable

enemies beset her at every turn.

Susan B. Anthony broke with other NWSA leaders to

support Grant in an attempt to distance

the movement from the increasingly scandalous Woodhull. After the family was evicted from their home, they could not even find a house to rent and for a while had to sleep on the floor of their newspaper

offices. Business deals fell through and speaking engagements were

cancelled. The paper had to suspend publication for four

months. When it returned it ran a full

expose of the Beecher/Tilton affair

and another on a prominent broker

with a predilection for young girls. While circulation

soared, the sisters were sued for

libel and prosecuted for pornography.

Woodhull spent Election

Day in jail. No

votes were recorded for her, but it is assumed that some of the 4000 or so rejected ballots in the election were

for her.

Her legal

difficulties dragged on. In 1874

both sisters were finally cleared of

criminal charges. But they had to pay fines and court costs amounting to an astonishing

half a million dollars. All of the sisters’ assets, including their brokerage accounts, printing press, personal papers, and

even their clothing were seized to pay the fines. By 1876 she was divorced from Col. Blood and

her beloved newspaper was silenced.

She turned to the comforts

of religion while continuing to eek

out a living as a lecturer. After

Cornelius Vanderbilt died unhappy heirs

attempted to subpoena the sisters

for testimony that he was not of sound

mind. Somehow—and speculation runs heavily to the Vanderbilt

estate—money was found to send

the sisters to England with a comfortable stipend on which to live. Victoria lectured there, but her message was subdued.

She met a wealthy and conservative banker, John

Biddulph Martin and married him in 1882 and settled into a life of respectability and sponsorship of various humanitarian causes. On a trip back to the U.S. she joined the

tiny Humanitarian Party and was

nominated as their candidate for President in 1892. It was a last

hurrah in the United States.

Back in England Victoria divided her husband’s estates after his death and backed a scheme to rent small plots to

impoverished women so that they could become self-sufficient, founded an experimental

school, and sponsored an annual

agricultural fair. She was active in World War I relief work. She

died in her sleep on June 9, 1927 at

the age of 88 at her estate in Bredon,

Worcestershire

Please correct your blog. You refer to Victoria as "Virginia." Thanks

ReplyDeleteIt took me a while to find it since I used the name correctly 14 time. Evidently my fingers were thinking of something else when I typed that paragraph and, of course, it did not get caught by spell check. If you read my blog you will have tons of opportunities to correct me. It't a one person pop stand and I am a semi-literate...

Delete