| White rioters attack a car of people who attended a heavily guarded Paul Robeson concert in Peekskill, New York in 1949. |

Note: The rise of Donald Trump and the increasing belligerent violence of many of his

supporters remind us that the ugly lessons of the Peekskill riots cannot be

forgotten.

It should have been a pleasant Sunday

in the country. But on September 4, 1949

the residents of up-scale, White

suburban Westchester County New York got together for a well-planned riot. It was the second one in a week. It was inflamed

by headlines in a respectable local

newspaper. It was largely organized by the local Posts of the American Legion

and the Veterans of Foreign

Wars. Members of the Ku Klux Klan from far and wide came to

give the locals a hand and some technical

advice—and signed up more than 700 new

members. It was overseen, protected, and participated

in by local police, sheriff’s

deputies, and State Police. When it was over most of the national media heartily approved. Members

of Congress cheered the rioters

and blamed the victims using on the

floor of the House the vilest racial epithets available. The Governor

of the state of New York, a famous

former crusading District Attorney and

twice the nominee of the Republican Party for President of the United States not only

refused to investigate but—you

guessed it—blamed the victims. All

because a Black man wanted to sing

and a bunch of people—many of them Jews from

New York City--wanted to come and

hear him.

The object of all of this well-orchestrated fury was Paul Robeson, one of the most

celebrated—and reviled—Black men in the United States. Then 51 years old, he had already led a remarkable and accomplished life.

Robeson was born on April 9, 1898 in

Princeton, New Jersey to a former slave and Presbyterian minister, the Rev.

William Drew Robeson and his mixed

race Quaker wife, Maria Louisa Bustill

Robeson. That made him by birth one of a tiny elite

of American Negros. When he was

just 3 his father was forced out of his long-time pulpit by the Presbytery

despite the strong support of his Black congregation and the family was

quickly plunged into poverty.

Shortly after, his nearly blind mother was killed in a kitchen

fire. The senior Robeson finally

found a place at an African American Episcopal congregation some years

later and the family’s lot improved.

Paul

attended Somerville

High School in Somerville, New Jersey where

despite prejudice, everything he touched seemed to turn to gold. Already towering over his classmates the powerfully

built young man lettered in football, baseball, basketball, and track.

He added his powerful bass

voice to the choir and

discovered a love a performing while

acting in student productions of Julius Caesar and Othello. Academically he was at the head of

his class. And none of these

accomplishments shielded him from racial

taunting, which he dealt with by following his father’s advice—keep your head up, ignore

insults, be unfailingly polite,

and never lay your hands on a white man.

|

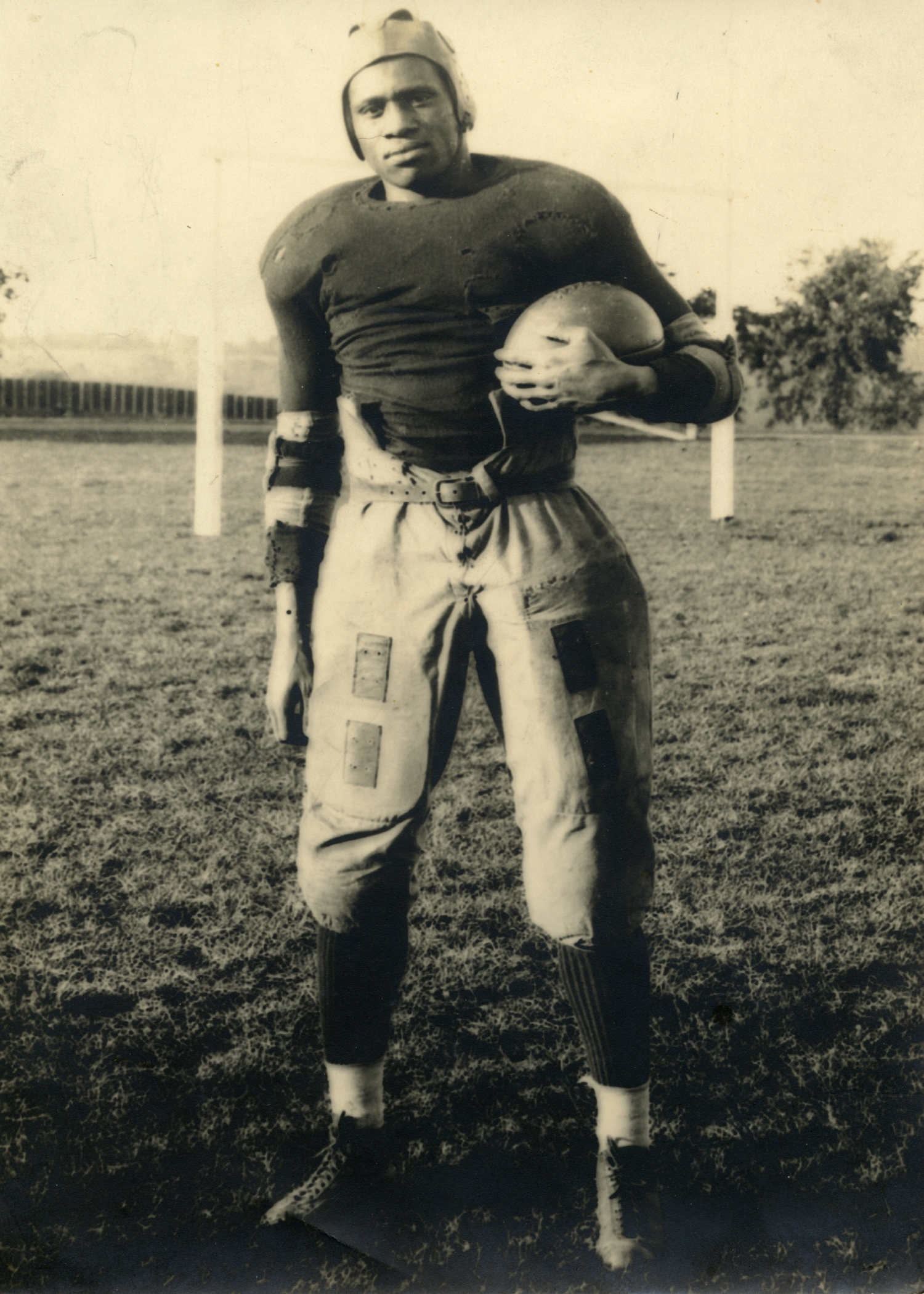

| Paul Robeson, Rutgers All-American end. |

In his senior year Robeson won a state-wide

competition for a full, four year

scholarship to Rutgers which he

entered in 1915 as only the third Black ever to attend the university and the only one during his entire tenure. As a freshman

he was a walk-on for the football team, accepted by the coach over the objections of his other

players. By the end of a stellar college

career he was twice a first team

All-American at end and

considered by Walter Camp to be the greatest player ever at that position. Yet he was benched when Southern teams

refused to play with a Black on the field.

Robeson also repeated triumphs on

stage and academically. He added champion debater to his resume, took home the annual oratorical prize in each of his four years, earned his Phi Beta Cap key, was elected to the

elite Cap and Scull Society, and

ultimately was elected class valedictorian. He did all of this while working for meal money, singing

off campus for cash, and in his last two years regularly commuting home to

care for his dying father.t

His college career caught the eye of

W.E.B. Du Bois who profiled the

student in The Crisis.

After graduation, Robeson enrolled in New York University Law School supporting himself as a high school

football coach and as a singer. He felt

the sting of racism at NYU, moved to Harlem

and transferred to Colombia Law

School. Despite consistently high

grades, it took Robeson four years to complete law school. He interrupted his studies to play professional football at Akron and then with the Milwaukee Badgers in the inaugural 1922

season of the National Football

League. He also took time to appear

on Broadway in the hit all-black revue Shuffle

Along and in Taboo, an ante-bellum plantation drama produced at Harlem’s Sam Harris Theater in the spring of

1922. Later he would travel to London for a production of the play supervised by the famous actress Mrs. Patrick

Campbell who added more musical

numbers for Robeson.

Despite these interruptions,

distractions, and a rising reputation as a leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance, Robeson graduate

law school with honors in 1923. By now

married to Eslanda Cardozo Goode—Elsie—an anthropologist and activist,

Robeson did not practice law for

long. He found his race was a barrier to the kind of career he had

imagined. Instead, with Elsie’s

encouragement, he turned to a full time

career as an actor and singer with his wife as his manager.

| Liftin' that bale as Joe in Showboat in London. |

By the mid ’20 he had triumphed in a revival of Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, which he also took to London, and more

controversially had appeared in O’Neill’s stark and damning racial drama All

God’s Chillun Got Wings in which he played a Black man who metaphorically consummated his marriage with his white wife by symbolically emasculating himself. Needless to say that controversial topic created uproar across the country. He also teamed with pianist Lawrence Brown to tour

the United States and Europe with a hugely successful program of Black spirituals and folk music. RCA Victor signed

him to a record contract.

In Europe, particularly France, Robeson experienced a freedom from prejudice that he had

never experienced at home. He found

himself welcome in intellectual and expatriate communities by the likes of Gertrude Stein and Claude McKay.

In 1928 Robeson starred as Joe in the

London production of Jerome Kern’s Showboat where his famous rendition

of Ol’

Man River became the standard

upon which all subsequent productions would be judged. The show was much more successful in London

than it had been in its first New York run and lasted for more than a year at

the prestigious Covent Garden

Theater. He followed up with the experimental film Borderland opposite

his wife.

Back in London he appeared in an

acclaimed Othello opposite Peggy Ashcroft as Desdemona which led to an affair

with Ashcroft that nearly cost him his marriage.

| As Othello with Peggy Ashcrcroft, future Dame. An affair with the actress strained Robeson's marriage nearly to the breaking point. |

After the affair ended and the

couple reconciled, Robeson returned to Broadway for the great revival of Showboat in 1932. In 1933 he became the first Black ever to

star in a major Hollywood film, The Emperor Jones. Over the next few years he made several

films. Other than Showboat, most of them were British productions. Sanders

of the River, a tale of colonial

Kenya in which he played a local

chief who aids a sympathetic

colonial officer made him a major star in Britain. But Robeson was stung by criticism that the

part was degrading to Africans. That sparked a new interest in Africa and his

cultural roots, including the study of several African languages and

involvement in an emerging anti-colonial

movement.

It was associates in the anti-colonial movement that first brought Robeson

to Moscow. He contrasted what he found there to the

rising racism he observed in Nazi Berlin

and to continued Jim Crow rule in

the United States. He said “Here I am

not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life ... I walk in full

human dignity.” Two years later he sent

his son Paul, Jr. to study in Moscow to spare him the sting

of racism at home.

Inevitably Robeson and his wife

became drawn to the Communist Party,

which in the US was one of the few

movements that seemed totally open

to Black participation on an

absolutely equal basis. By the late

‘30’s he was spending more time as an activist and lending his talents to Party

causes—particularly to support of the Republican

cause in the Spanish Civil War—even

journeying to Spain in the dark hours to perform before and support the International Brigades. He also raised money for the cause at

several benefits and supported organizing drives by several unions.

When his manager complained that his political work was harming his

career, Robeson said, “The artist must take sides. He must elect to fight for

freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative.”

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-6534864-1436157137-2571.jpeg.jpg) |

| The 78 rpm album of Ballad for Americans with music by frequent collaborator Earl Robinson who would also compose I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night, one of Robeson's most famous songs. |

With the outbreak of World War II, Robeson returned to the

United States. The war years were marked

by personal and professional triumphs and by increasing controversy over his

politics. In 1939 he starred in the

hugely popular Ballad for Americans a patriotic cantata with lyrics by John La Touche and music by Earl Robinson which was aired on CBS Radio.

A recording became a bestselling album.

In 1940 Robeson starred in the Ealing Film The Proud Valley in which he played a Black American who finds

himself in Wales where he lends his

singing voice to the famous local men’s choirs and joins coal miners in the pits where he ultimately sacrifices himself. The film

was a fusion of Robeson’s political and artistic life and was well received in

Britain and initially in the United States.

But it would later be views as pro-labor propaganda as would the 1942 documentary

Native Land about union busting corporations. That film was based on the actual reports

of the 1938 La Follett Committee/s investigation of the repression of labor organizing. Robeson was off-screen narrator and provided music for the film.

In 1943 Robeson became the first

Black actor to portray Othello on Broadway, opposite Uta Hagen. Throughout the

war years he appeared at rally and benefits for various anti-fascist causes.

With the end of the war anti-fascism

suddenly became subversive, as did

Robeson’s continued anti-colonialist activities and his new crusade against lynching. As anti-Communist hysteria mounted, he

publicly came to the defense of accused Communists although he denied he was a

member of the Party. None-the-less two

organizations in which he was very active were placed on the new Attorney General’s List of Subversive

Organizations. Called before the Senate Judiciary Committee and

questioned about his membership in the Party, Robeson now vowed, “Some of the most brilliant and distinguished Americans are

about to go to jail for the failure to answer that question, and I am going to

join them, if necessary.”

| Campaigning with Henry Wallace, second from left, with Lena Horne in 1948. |

In ’48 Robeson took a leading role

in the campaign of former Vice President Henry Wallace for President on the Progressive ticket. At great

personal risk he campaigned for Black votes in the Deep South. As tensions with

the Soviet Union continued to rise,

he echoed Wallace’s Peace Platform

for accommodation with the USSR.

But it was an appearance at a

Communist sponsored World Peace

Conference in Paris in 1949 that started the chain of events that led to the Peekskill rioting. According to a transcription of the

proceedings, Robeson told delegates:

We in America do not forget that

it was the backs of white workers from Europe and on the backs of millions of

Blacks that the wealth of America was built. And we are resolved to share it

equally. We reject any hysterical raving that urges us to make war on anyone.

Our will to fight for peace is strong...We shall support peace and friendship

among all nations, with Soviet Russia and the People’s Republics.

Somehow—and

the heavy suspicion was on the intervention of American intelligence

operatives—the Associated Press (AP) substituted the following

“quote:”

We colonial peoples have

contributed to the building of the United States and are determined to share

its wealth. We denounce the policy of the United States government which is

similar to Hitler and Goebbels.... It is unthinkable that American Negros would

go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against the

Soviet Union which in one generation has lifted our people to full human

dignity.

The

alleged quote was widely reported and unleashed a torrent of criticism and

invective.

When the Civil

Rights Congress, one of the “front” organizations on the Attorney

General’s List announced that Robeson would headline a befit concert at Lakeland

Acres, just north of Peekskill on August 27, the Peekskill Evening Star condemned the concert and encouraged

people to “make their position on communism felt.” Although no overt threat of violence was

made, the town was soon abuzz with plans to not just demonstrate, but to

block the concert and prevent it from occurring. The Joint Veteran’s Council, spearheaded

by the American Legion openly boasted that they would physically

prevent any gathering.

Concert

organizers, who had twice before staged events there featuring Robeson, were

expecting demonstrators and heckling.

They did not expect what happened.

As the police stood off and refused calls for protection from

rock throwing, bat wielding mobs which attacked concert goers as they attempted

to reach the site by car. Several

people were injured. A large flaming

cross was observed on a nearby hillside and Robeson was lynched

in effigy.

Robeson arrived at the local commuter

line station where his long-time friend and Peekskill resident Helen

Rosen picked him up in her car. Attacks against visitors had been going on

for some time and she attempted to find a safe route to the concert site. As they neared they were taunted by chants

and jeers of “Niggers!” “Kikes!”

“Dirty Commies.” Robeson had

to be forcibly restrained from leaving the car to confront the rioters. Eventually Rosen turned around. Neither Robeson nor the audience reached the

concert site.

The Legion Post commander, while

denying that there was any violence during their “peaceful march” did boast to

the press, “Our objective was to prevent the Paul Robeson concert and I think

our objective was reached.”

The incident sparked national headlines. Much of the commentary supported the rioters. Even

many of Robeson’s former friends were now reluctant to come to the defense of a

Communist. Things were different in New

York radical and left labor circles. A Westchester Committee for Law and Order was

hastily assembled representing local liberals and unionists. They decided to invite Robeson back to

Peekskill and to demand protection from the local authorities. Separately a committee of workers from Communist led unions in the City including

the Fur and Leather Workers,

Longshoremen, and the United Electrical Workers vowed to supply security to insure that a

concert could be held safely. After a

new date. September 4, was announced, Robson appeared before 4,000 people at a support rally in Harlem. The stage was set for a renewed confrontation.

| Robeson was surrounded by veterans and New York labor union body guards as he performed under siege on September 4. |

The September 4 concert

was relocated to the Hollow Brook Golf

Course in Cortlandt Manor, near

the site of the original concert. 20,000

people showed up and safely got to the

grounds protected by hundreds of

union marshals who lined the

approach route and circled the concert grounds. Woody

Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and the Almanac

Singers performed before Robeson took the stage to thunderous

applause. Meanwhile a police helicopter swooped low over the

crowd sometimes making it difficult for the performers to be heard. Police did find one snipers nest apparently set

up to take shots at the stage.

Trouble erupted as concert goers attempted to get home. A convoy of busses from the city was attacked

near the intersection of Locust and Hillside Avenues. Police then diverted the long line of

vehicles including hundreds of cars, on a miles long detour lined with howling protesters who pelted the cars with

rocks, broke windows and beat on the

hoods and roofs with baseball bats and 2x4s. Several cars were

turned over. Some were set on fire. Many drivers and passengers were dragged from

their cars and beaten.

Among the cars attacked was one

containing Pete Seeger, his wife Yoshie,

their small children, Almanac member

Lee Hays, and Woody Guthrie. When the windows of the car were shattered

Guthrie tried to use a shirt to

cover one window and keep out the stones.

Unfortunately, Seeger later remembered, Woody used an old red shirt which just inflamed the mob. The occupants escaped serious injury. Pete

kept several of the stones that landed inside the car and used them in building

the fireplace chimney of his cabin in Fishkill.

One of those injured was Eugene Bullard, a World War I veteran and America’s first Black military pilot.

Both film footage and still photographs caught him being savagely beaten

by the mob who was actively joined by two local policemen and State Police

officer. Despite being clearly identifiable none of the officers were charged, or

even questioned about the assault.

Neither were many readily identifiable Legion members.

Finally union members and others

including novelist Howard Fast

succeeded in forming an arms linked cordon around the cars placing themselves

non-violently between the concert goers and rioters. They sang We Shall Not Be Moved as

rioters hurled curses and slurs. Several

were injured but stood their ground and the rest of the concert goers finally

got out relatively safely.

At least 140 people were treated for

injuries, and some of the injuries were serious. Many others suffered lesser wounds.

In the aftermath of the riot Governor Thomas Dewey turned aside a delegation of 300 who

came to Albany to demand and

investigation into the riot. Dewey

refused to meet with them and blamed the riot on Robeson for insisting on

singing where he wasn’t wanted.

In the House of Representatives Congressman John E. Rankin of Mississippi castigated Robeson and

attacked liberal Republican Reprehensive

Jacob Javitz of New York for daring to defend the right of free speech, “It

was not surprising to hear the gentlemen from New York defend the Communist

enclave… [the American people are not in sympathy] with that Nigger Communist and that bunch of Reds

who went up there.” Congressman Vito Marcantonio of the American Labor Party protested the use

of the word Nigger. He was ruled out of

order by Speaker of the House Sam

Rayburn of Texas after Rankin

reiterated, “I said Nigger, and I meant it!’

Despite protests by some civil libertarians, liberal and religious groups, the general public

went along with the dominant press

narrative that the violence, though “deplorable”

was the responsibility of Robeson

and his allies for insisting on performing.

No one was ever prosecuted for the numerous assaults and damage to

property. A civil suit filed on behalf of several of the injured languished in

court for three years before being dismissed.

As for Robeson, his career was essentially over in the

United States. Over 40 planned concert

dates were canceled because of fear

of violence. He was effectively blackballed from film work, radio, and

infant television. His recordings and films were withdrawn

from circulation. Even in college football records were erased.

In 1950 Robeson’s passport was revoked and all American ports

and international airports were put

on alert to prevent him from leaving the

country. He was not allowed to

travel again internationally until 1958, effectively silencing him both at home and abroad and leaving him virtually without

any source of income.

When his passport was finally

returned, Robeson resumed touring internationally based out of London, although

he could seldom find a booking in the United States. Refused numerous entreaties to denounce

Communism in exchange for a return to favor, or even a chance to work publicly

with the growing American Civil Rights

Movement which felt compelled to keep him at arm’s length. He followed the Party line during de-Stalinization, He visited the Soviet

Union again, even spending time with Nikita

Khrushchev at his vacation dacha.

Robeson was in Moscow in 1961 when

he suffered a complete breakdown, slashing his wrists in locked

bathroom. He reported paranoia that he was being watched

constantly—which he undoubtedly was by both US agents and the Soviets, but also

reported unusual and sudden delusions

and hallucinations. The onset of the breakdown was so sudden

and the symptoms so dramatic that some biographers believe that he may have

been slipped hallucinogens by

American intelligence services in an attempt to discredit and silence him.

After years of treatments in the

Soviet Union, London, and East Germany, Robeson returned to the United States a

broken man. Aside from a couple of appearances, he

retreated into isolation living as a virtual

hermit until dying of a stroke in

his Philadelphia home in 1977. His death revived interest in his career and slowly his old records and films

became available again.

He was always a hero to the Black

community, but in death he rose to be a cult

figure on the white left far beyond his shrinking Communist community. A lot of those people in trying to rehabilitate his image down played his

loyalty to the Party or portrayed him as a naïve

dupe.

Robeson would have had none of

it. He remained to his dying day a

defiant Communist, long after many of his former comrades like Pete Seeger had left the party out of disgust with Stalinism and the authoritarian

repression of popular uprisings like that in Hungary. For him the

Communists were always the ones who had accepted him without question or

reservation and who as far as he could see were on the right side of the

struggles he cared about—anti-colonialism, civil rights, labor, and peace. He would not turn his back on them despite

the enormous personal cost.

Even today Robeson’s legacy is a

challenge for those that defend civil liberties even when the speech involved

is highly unpopular.

No comments:

Post a Comment