|

| Elijah P. Lovejoy shortly before his death. From a broken glass plate. |

He

was by almost all accounts, a difficult

man to like. Opinionated to the point of bigotry on innumerable subjects. A totally humorless religious zealot

consumed with the conviction of his own

righteousness—and the sinfulness of

just about anyone who did not agree with

him on everything, down to the comma placement. But such men—and women—often are what are

needed to begin moving the fulcrum of

history. When Elijah P. Lovejoy was cut

down in a hail of bullets defending

his precious printing press from an Alton, Illinois mob on November 7, 1837

he became the first important martyr of

abolitionism and helped galvanize the infant movement.

Lovejoy

was born on November 9, 1802 on the frontier

farm of his Congregationalist

minister father, the Rev. Daniel

Lovejoy and his zealous Christian wife in Albion, Maine. While most ministers of the New England Standing Order were highly educated at Harvard or Yale, Elijah’s

father was prepared for service on

the fringes of civilization by reading with other ministers. He keenly

felt his educational deficiency and impressed

the need for academic achievement on his oldest son and his siblings. Both parents, but particularly his mother,

emphasized it was his duty to fight sin

and prepare the world for an imminent

Second Coming

After

the customary attendance at rude rural schools and attending more

ambitious academies in Monmouth and China, Maine, Elijah enrolled

in the tiny Waterville College, a Baptist school that was both all he could afford and which was imbued with righteous Christianity. He was a serious,

sober, dedicated student who impressed

the faculty and alienated his more fun

loving classmates for the same reason.

When he wasn’t studying, he was praying

to have the conversion experience that

would mark him as one of the saved. Alas, it did not come and the young man tortured himself with guilt over his unworthiness and fear for

his immortal soul.

By

the end of his second year, he was hired

as an instructor in the College’s preparatory

school. He graduated at the top of his class in 1826. Lacking the longed for conversion, Lovejoy felt unworthy to continue his planned education as a minister. He continued to teach, but yearned to find some other way to serve God.

After consultation with his mentors at the College, he decided the best course would be for him to head west,

presumably a land of sinners

requiring the stern admonitions of a

faithful servant of the Lord.

He

went to Boston, to get work to finance his trip. Finding

none, with virtually no money, but grim determination, Lovejoy set out to reach his new life on foot.

After

weeks of tramping, Lovejoy arrived

in New York City foot sore and broke.

He decided to rest some and replenish

his exhausted purse. He arrived in

the City in June of 1827 and found work of sorts—peddling subscriptions to the Saturday Evening Gazette. The job required hours of walking block after block knocking on

unfriendly doors and accosting

prospects in the streets. Customers were few and commissions slim. In desperation Lovejoy wrote his mentor,

Waterville College President Jeremiah

Chaplin, who sent his favored former pupil enough money to resume his

journey.

Still

traveling mostly by foot, but occasionally parting

with a few precious coins for short

passage on canal boats or river flat boats, Lovejoy finally

arrived at Hillsboro, Montgomery County in

southern Illinois that fall with the

intention of settling. He found a village barely four years old that made

Albion look like a sophisticated

metropolis. It was a brawling, profane frontier village where

life centered on fiercely competing grocery store/taverns and settled mostly by Scotch Irish pioneer stock via Kentucky

and other backwoods settlements

of the upper South. He was shocked

and appalled. He saw little

opportunity to save the heathens he

observed. Better, he concluded to push on to the acknowledged capital of the hinterlands, St. Louis.

|

| Flatboats still dominated commerce when Lovejoy arrived in bustling St. Louis in 1828. |

St.

Louis in 1827-28 was a busy, prosperous place indeed. It was the hub of river commerce on the Mississippi. Flatboats rafted lumber and crops south and poled their way laboriously north laden with the manufactured and luxury goods of the world. It was enjoying a special boom as the outlet of

a thriving and growing fur trade

that was trapping the rivers and streams of the far-flung former Louisiana

Purchase all the way to the Rocky

Mountains. It was also a slave state holding thumb pushing far

north alongside neighboring free state Illinois. The population of the state was mostly

drawn from the same Scotch Irish pioneer stock that had so offended Lovejoy

with a sprinkling of younger sons of

the southern aristocracy seeking to establish

their own plantations or enter the gentlemanly

professions of lawyer, doctor, or

editor.

St.

Louis, however, as a successful

commercial city, had also attracted

fair numbers of Yankees and New Yorkers, the well educated sons of the first or second generation of the New England diaspora. These folks dominated commerce and trade in

the city and were building fine homes. They yearned

to establish a civilization that like beloved Boston could become a “shining city on the hill.” Lovejoy was just the kind of earnest young

man embodying all of the fine moral

virtues of New England plus scholarship

that they could use.

Lovejoy

found a spiritual home among local Presbyterians. Like most Congregationalists far from the

orbit of New England he found their shared,

strict old school Calvinism familiar

and comforting even if there were minor differences of polity. Since the Congregationalists resisted, at this point, missionary zeal for the west and their well educated clergy fell disinclined to

test out the wilderness, the Presbyterians offered really the only viable alternative. The local Baptists he encountered were not

like the serious and sober gentlemen of Waterville College, but were served by ill-educated sometimes self appointed

circuit riding shouters who seemed to

appeal mostly to the illiterate and unwashed. The Methodists

were hardly better, if perhaps more literate.

One

fly in the ointment was that

Presbyterianism was also the native

religion of the Scotch Irish, at least those had not given over completely to Godless heathenism or been converted by saddlebag evangelists. It was the best class of the rowdy lot, and many of the ladies were both virtuous

and pious. But the men, outside of Sunday morning, were often profane and given to a stubborn

affection for whiskey. The Scots

Irish and for the New England exiles somewhat uncomfortably worshiped together.

With

the help of his new co-religionists,

Lovejoy quickly established himself as a

school master and was soon able to open

his own academy for the sons and daughters of the city’s Yankee elite. He approvingly described the families of his pupils as “the most

orderly, most intelligent, and most valuable part of the community.”

Lovejoy

prospered in the respect of his

chosen community and was finally fairly financially

secure. But he was still restless. He was not doing enough to fulfill his self-appointed mission.

In

1830 a new opportunity arose,

however. He bought a partnership in and became editor of the St. Louis Times. It was a political

paper, fiercely anti-Jacksonian, which suited Lovejoy

who was practically a genetic Federalist. Much of Missouri was staunchly behind Old Hickory

and his re-made Democratic

Party. But in St. Louis another

western politician, Henry Clay of Kentucky was popular. He had been the architect of the Missouri Compromise and his proposed

American System with its support for the National Bank, internal

improvements, and a protective

tariff resonated with Lovejoy. He

poured passion—and vitriol—into his role as a political

editor.

He

also promoted causes dear to him—teetotalism, general public morality and order, civic improvement, and education. He used his rising influence to help found

the local Lyceum and to back the Missouri and Illinois Tract Society producing missionary tracts or moralistic

screeds for distribution through the region. But the

issue of slavery did not yet move him much.

It was a major part of the local

economy and practically taken for

granted in the culture. If he had

any Yankee qualms about it he kept them largely to himself. In fact his newspaper advertised slave auctions and wanted

notices for escaped slaves.

Then,

in 1832 came the thunderclap that

changed his life. The Rev. David Nelson came to town to preach a revival over several weeks at the First Presbyterian Church. Lovejoy

dutifully attended the daily

meetings. He found himself soon under the sway of Nelson’s powerful preaching. Before the revival was over, he finally had

the personal conversion experience

he had long prayed for. He also was attracted a second message preached by Nelson—the moral necessity of ending slavery.

Lovejoy

decided the time was finally right for

him to become a minister. He headed

east and enrolled in the Princeton

Theological Seminary. Completing his

studies in a year, he was granted his license

to preach by the Philadelphia

Presbytery on April 18, 1833.

He

returned to St. Louis a rejuvenated man. He established

his own Presbyterian congregation for his Northern supporters. His

supporters underwrote a new newspaper,

the St.

Louis Observer which was dedicated less to sectarian politics and more

to reform and moral uplift.

It was Lovejoy’s unrestrained

voice, unleashed with passion.

In

the very first issue he excoriated Catholicism and Papism in vitriolic language. The

language was familiar to any Calvinist ear from the east. But St. Louis, a former French and Spanish provincial

capital, had a large Catholic

population and there had been a general

toleration of religious differences as the city had grown. Not only were his targets outraged, but so were some other Protestants. In his first issue Lovejoy established a reputation as an extremist and a bigot.

Undeterred

by the storm of criticism, he

pressed on with attacks on Catholics as well screeds against alcohol, Sabbath

breaking, and profanity. And

finally, slavery.

His

editorials were unflinching in his

denunciation of the moral evil of human bondage. But at first he was also critical of the kind of abolitionist

absolutism preached in William Lloyd

Garrison’s The Liberator. He denounced

imposing abolition instead hoping that argument

and religious conversion would change the hearts of slave holders who

would see the error of their ways

and free their slaves. Despite the seeming moderation of this stance, it still outraged the Southern dominated city. By the summer of 1835 citizen’s committee passed a

resolution aimed at Lovejoy declaring anti-slavery

agitation inspired “insurrection

and anarchy, and ultimately, a disseverment of our prosperous Union.”

As

controversy swirled around him,

Lovejoy married a fine Christian woman,

Celia Ann French, the same year.

Married bliss did not mellow Lovejoy. As public clamor against his anti-slavery

stand grew, so did his defiance. In fact the reaction drove him ever more closely into the arms of the abolitionist

extremists he had once derided. Several times Lovejoy was accosted on the streets and barely escaped assault. His office

and shop were vandalized. In response he printed a string of editorials vigorously defending the rights of freedom of the press and to express unpopular opinion.

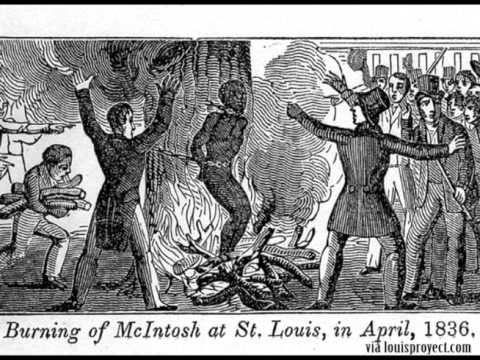

Things

came to a head in April 1836 when a Black riverboat hand, Francis McIntosh allegedly killed a deputy sheriff and injured other men in the posse

sent to arrest him. An outraged

mob was not content to wait for a

trial. They broke into the courthouse jail and lynched McIntosh. Despite overwhelming

evidence that McIntosh was guilty,

Lovejoy denounced the mob action

writing “We must stand by the

Constitution and laws, or all is gone.”

After that editorial angry mob twice

entered the offices of the Observer and

seriously damaged the printing press.

When

the Grand Jury failed to indict any

of the known leaders of the lynch

mob, Lovejoy railed against the

injustice and the actions of the

aptly named the presiding judge,

Luke E. Lawless who virtually laid out a legally questionable defense

of the accused men. Another mob gathered

and attacked the office, this time throwing

the press out the window and into

the streets.

Lovejoy

finally concluded it was unsafe to

continue in St. Louis. He decided to

relocate to Alton, Illinois, upriver and 15 miles north of St. Louis.

He hoped that the free state would be more welcoming. Vigilantes however followed Lovejoy’s

move and when his precious press was unloaded

to the quay in Alton, they threw it

in the river.

Despite

this set back, Lovejoy at first received

a cautiously warm reception in his new town. It was a growing

city and its boosters envisioned it

as a possible rival to St. Louis itself.

Despite a local population that was largely Southern in origin, some

felt that the establishment of a new paper—and likely the founding of a new

Presbyterian Church would enhance the

city’s reputation in its bid as a

long shot contender for the relocation

of the new state capital from Vandalia.

As

Lovejoy raised money for a new

press, he met with a local citizens

committee which offered him a conditional

welcome—if he would refrain from the

kind of “agitation” that had caused trouble in St. Louis. Lovejoy assured them that he now planned a purely civic and Christian paper.

Shortly

after New Year’s 1837 the new Alton

Observer began publication. And

despite his promises the very first

issue contained a blistering attack on slavery and slavery apologists. By

spring he was calling on the citizens of

the town to sign an abolitionist petition to the state legislature. Then he urged citizens to “walk the streets of the town” pressing an anti-slavery

message. In August he called for a founding convention of an Illinois Anti-Slavery Society for the

town. After printing a broadside for the meeting, a mob once

again stormed his shop and threw another press into the river.

| Another one of Lovejoy's printing presses smashed. |

Lovejoy,

now attracting national support,

ordered another. But when that one was

delivered, it was discovered on the dock

and also deep sixed.

The

proposed Anti-Slavery convention tried to convene in Alton in October, but pro-slavery

men packed the meeting and prevented

resolutions from being passed

and business conducted. Lovejoy and his supporters then convened again in secrecy at another

location. In addition to founding the society, money was raised

to buy yet another press and to defend

it with force, if necessary.

Lovejoy

tried one more time to reach accommodation with his enemies in Alton. He arranged a meeting with them at which he

made an impassioned plea for freedom of the press which has become regarded as

a classic. On November 2 he said this to

the assembly:

It is not true, as has been charged upon me, that I

hold in contempt the feelings and sentiments of this community, in reference to

the question which is now agitating it. I respect and appreciate the feelings

and opinions of my fellow-citizens, and it is one of the most painful and

unpleasant duties of my life, that I am called upon to act in opposition to

them. If you suppose, sir, that I have published sentiments contrary to those

generally held in this community, because I delighted in differing from them,

or in occasioning a disturbance, you have entirely misapprehended me. But, sir,

while I value the good opinion of my fellow-citizens, as highly as any one, I

may be permitted to say, that I am governed by higher considerations than

either the favor or the fear of man. I am impelled to the course I have taken,

because I fear God. As I shall answer it to my God in the great day, I dare not

abandon my sentiments, or cease in all proper ways to propagate them.

I, Mr. Chairman, have not desired, or asked any

compromise. I have asked for nothing but to be protected in my rights as a

citizen--rights which God has given me, and which are guaranteed to me by the

constitution of my country. Have I, sir, been guilty of any infraction of the

laws? Whose good name have I injured? When, and where, have I published anything

injurious to the reputation of Alton?

Have I not, on the other hand, labored, in common with

the rest of my fellow-citizens, to promote the reputation and interests of this

City? What, sir, I ask, has been my offence? Put your finger upon it—define it—and

I stand ready to answer for it. If I have committed any crime, you can easily

convict me. You have public sentiment in your favor. You have juries, and you

have your attorney, and I have no doubt you can convict me. But if I have been

guilty of no violation of law, why am I hunted up and down continually like a

partridge upon the mountains? Why am I threatened with the tar-barrel? Why am I

waylaid every day, and from night to night, and my life in jeopardy every hour?

You have, sir, made up, as the lawyers say, a false

issue; there are not two parties between whom there can be a compromise. I

plant myself, sir, down on my unquestionable rights, and the question to be

decided is, whether I shall be protected in the exercise and enjoyment of those

rights…

I have no personal fears. Not that I feel able to

contest the matter with the whole community; I know perfectly well I am not. I

know, sir, you can tar and feather me, hang me up, or put me into the

Mississippi, without the least difficulty. But what then? Where shall I go? I

have been made to feel that if I am not safe at Alton, I shall not be safe

anywhere. I recently visited St. Charles to bring home my family, and was torn

from their frantic embrace by a mob. I have been beset night and day at Alton.

And now, if I leave here and go elsewhere, violence may overtake me in my

retreat, and I have no more claim upon the protection of any other community

than I have upon this; and I have concluded, after consultation with my

friends, and earnestly seeking counsel of God, to remain at Alton, and here to

insist on protection in the exercise of my rights. If the civil authorities

refuse to protect me, I must look to God; and if I die, I have determined to

make my grave in Alton.

The last

sentence proved all too accurate a prediction. The meeting broke up with a resolution once again denouncing Lovejoy

and demanding that he and his newspaper

immediately leave the city.

Within days a new press arrived and under cover of darkness and armed guard it was moved by stealth into the relative

safety of a sturdy stone warehouse

near the river. Lovejoy and a small volunteer militia of armed abolitionists stood guard. It did not take long for the local citizenry

to discover what had happened.

After reinforcing

their courage at local taverns, a mob marched on the warehouse after 10 pm

November 7. A spokesman demanded the

press be turned over to the mob. After a

curt refusal the windows of the

warehouse were shattered with rocks and then the mob rushed the door. There seems

to be no doubt that Lovejoy or his followers fired the first shot. A general gunfight broke out. At least one member of the mob was killed and others injured.

|

| A mob attacking the warehouse of Godfrey & Gilman in Alton, Ill., where the abolitionist Elijah Lovejoy was killed. |

After briefly retreating to consider the situation, it was decided to try and smoke Lovejoy out by setting fire to the

roof of the three story warehouse.

There was a lull until a long

ladder could be found. Then under heavy cover fire the ladder was rushed forward and a man with a torch started to climb it. Lovejoy and a supporter darted out from the building, knocked

the ladder over, and the safely

returned inside.

A second

attempt was made. Lovejoy again sallied forth, this time he was cut down by at least 5 shotgun slugs in the

chest. He managed to cry, “My God, I’m

hit” before staggering back inside.

He died almost immediately.

Meanwhile the mob succeeded in torching the roof.

Lovejoy’s grief stricken

companions managed barely to escape out a back door and flee along the

river bank. The mob broke the door down and found Lovejoy

dead. Then they went about their methodical work. They carried the press and cases of type to the top floor of the building then threw it out the window. The mob, armed

with hammers and stones continued to

smash parts tossing them into the river.

They then left, leaving Lovejoy’s

body, spit upon and abused, behind.

Two days later with little ceremony and in

secret he was buried in a field near

his home. Evidence of the grave was erased and it was left unmarked lest it be disturbed.

It remained so until 1860

when supporters finally erected a

headstone. Lovejoy’s wife, already

in ill health, could not attend the burial.

William Lloyd Garrison and The Liberator spread the

word of the murder. Abolitionist speakers fanned out across the North

claiming Lovejoy as their first martyr.

Elijah’s younger

brother Owen, a Congregational

minister, came to Illinois to finish his brother’s work and became the longtime leader of state Abolitionists. From 1857 until his death in 1865 he served

as a Republican Congressman from the

state where his brother died.

Today if you visit Alton you can see the grave, his relocated home, and a handsome

monument—a 110 foot column

surmounted by an Angel. Ask anyone in town and they will be glad to tell you the story. And despite the fact that many local families have been there since

Lovejoy’s death, you won’t find any

who will acknowledge that their ancestors were part of the mob.

The photo at the top of this article is of Owen Lovejoy, Elijah's brother, not of Elijah himself. I don't believe a photo of Elijah exists, photography was too new. Owen became a well known abolitionist leader and politician, and there are several good photos of him including this one.

ReplyDelete