Last Friday night my wife Kathy Brady-Murfin and I took in a

production of the radio play version of It’s A Wonderful Life by the Woodstock Musical Theater Company at the Woodstock Opera House. It

was this year’s fulfillment of a tradition of attending a holiday show during the Christmas Season that began when I gave up working my night job on Friday nights.

We came in full of the Christmas

spirit after taking in the spectacular annual lighting of Woodstock

Square earlier in the evening. And

we had a great time.

The

production had all of the virtues—and

some of the problems—of community theater. We have been attending a lot of very good professional theater in recent years

and even a very good amateur

production can’t be held to the same

standard.

On

the plus side the silver and black art

deco set by designer Barry R. Norton

was spot on and the equal of any static set you could see at any

theater. The costumes by co-producers and

wardrobe maven Kathy Bruhnke—a theater veteran and old personal friend were perfectly authentic 1946. Because this was supposed to be a radio play,

the costumes are for the most part meant to be the actors’ street clothes, not the characters’ clothes. Occasionally a change of hat or cap or the addition of jacket was used as a cue to

a specific character, like the uniform

cap for Burt the Cop.

Director Regina Belt-Daniels chose to open up Joe Landry’s script in a couple

of significant ways. To better mirror a

period radio broadcast she expanded the

role of the announcer and added a close

harmony female quartet to sing a

program theme song, advertising jingles, and a couple of contemporary popular songs a la the Andrews Sisters. She also

greatly expanded the script’s called

for cast of 5 actors, standard for live radio drama in those

days with each actor playing multiple

roles, to 13 including four children, who would have been voiced by an actress. With the exception

of the three leads playing George and Mary Bailey, Mr. Potter and the children, each actor still has

multiple parts, but far fewer than with a 5 person cast. This allows for better differentiation between characters portrayed by actors who may not

have mastered the multiple voices

required of a radio pro. On the other hand the shuffling of all of those actors to the three microphones at the front of the sage was sometimes a tad clumsy.

The

cast, with varying levels of experience

and skill, was necessarily uneven and some had occasional difficulty

reading from a script or quickly picking up cues. The principals

were solid. Mathew Schufreider as George channeled a young James Stewart without opting for imitation of Stewart’s voice and mannerisms. Heidi Allen was appropriately sweet, resolute, and loyal. Robert Wilbrandt, a local siting judge with wide community

theater experience, was a perfectly villainous

Mr. Potter. But for my money the

performance of the night was turned in by little Lia Hyrkas as ZuZu the

only actor to work from memory without a script and who was both perfectly natural and charming.

As

entertaining as the evening was, of course, nothing could make us forget the play’s

source.

Despite

stiff completion from films like Miracle

on 34th Street, A Christmas Story, White Christmas, various versions of

The

Christmas Carrol, and more recent fare like Elf and the Polar

Express, Frank Capra’s 1946

film It’s

A Wonderful Life remains the most

beloved popular holiday movie and still makes lists of the best films of

all time. It was the personal

favorite of its director, its

star James Stewart, and of its leading lady Donna Reed.

Legend has it that the

film was a total failure upon its release. Not

quite so. It opened to strong reviews and good audiences on December 20, 1946. But it faced stiff competition in the

theaters that holiday season—Disney’s Song of the South, The

Best Years of Our Lives, John

Ford’s My Darling Clementine, and

the epic Technicolor western Duel in the Sun among others. Released

just 5 days before Christmas, the film did not have time to build a holiday audience and in those

days interest in Yule flicks faded

as soon as the tree came down, then

generally the day after the holiday or no later than New Year’s Day.

But

the big problem was the cost of the film. The independently produced film was partly financed and released by RKO Studios which

bet on Capra on the strength of his enormously popular pre-war populist hits

at Columbia. He had a relatively

lavish budget which he over ran

the budget spending lavishly on a top cast and on the elaborate Bedford Falls sets. In the end, it cost a $3.8 million—a lot

for black and white comedy/drama—and

just barely recouped the expense in

its first release. The studio didn’t make a dime.

Despite

that disappointment, the film was

recognized for its importance and quality. It was nominated for five Academy Awards including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor and won a technical effects award. It also won Golden Globe and National

Board of Review awards. By no

stretch of the imagination could it be called a failure.

|

| Frank Capra and James Stewart share a laugh during the filming of the picture's grim suicide scene. |

Capra

had returned from his World War II

service a changed man. Four days

after the attack on Pearl Harbor on

December 7, 1941 he gave up his lucrative career during which he had

experienced unprecedented success

with films like It Happened One Night, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Lost Horizons, You Can’t

Take it With You, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and Meet

John Doe as well as his presidency

of the Director’s Guild to

enlist in the Army. He was personally tapped by Army

Chief of Staff General George C. Marshal to create and lead his own documentary film unit outside of the

usual Signal Corps authority under Marshall’s

direct command.

As

a result Col. Capra produced and directed or co-directed Why We Fight, seven

feature length documentaries including Prelude to War (1942), The

Nazis Strike (1942), Divide

and Conquer (1943), The

Battle of Britain (1943), The

Battle of Russia (1943), The

Battle of China (1944), and War

Comes to America (1945). The

films were shown to GIs to explain in an understandable way why they were going to war and used unprecedented battle action sequences filmed on all fronts and oceans. Marshal considered them so powerful that they were

release for theatrical showings in the U.S. and Britain. Prelude to War was awarded an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. Outside

of that feature Capra also made The

Negro Soldier in 1944 and Know Your Enemy: Japan, Here Is Germany, Tunisian Victory, and Two Down and One to Go all in

1945. Capra always considered these

films the most important of his career.

Hollywood

had just been reminded of how popular a film maker Capra was when Arsenic

and Old Lace, which had been hurriedly filmed for Warner Bros. in 1941 starring Cary

Grant, Pricilla Lane, and Raymond

Massey, was finally released after the long run of the Broadway production, was finally released in 1944. Every studio in Hollywood wanted to sign him,

but Capra, who had a bitter and

contentious relationship with his longtime

boss at Columbia Pictures, was

determined never again to be under the

thumb of a studio boss and to

have total creative control over his

pictures.

Capra

and two other directing powerhouses—William Wyler and George Stevens, formed Liberty

Films, The first independent company

of directors since United Artists in

1919 and one of a tiny handful of independent studios like Selznick International Pictures and

Samuel Goldwyn Productions

that aspired to produce A list films in head-to-head completion with the

major studios. With Wyler and

Stevens finishing up their studio commitments, Capra was slated to helm

the first product.

For source material Capra turned to an obscure

short story by magazine editor and Civil War historian

Philip

Van Doren Stern. Stern wrote the story after experiencing a vivid dream obviously

influenced by Charles Dickens’ A

Christmas Carol in 1938. He

tinkered with the tale for a few years before trying unsuccessfully to find a

publisher for it. In 1943 he privately

printed an edition of 200 as The

Greatest Gift which he distributed to friends as Christmas gifts. It finally found magazine placement with a literacy

journal before Good Housekeeping picket

it up for its January 1945 issue as The Man Who Was Never Born.

Somehow

Cary Grant spotted it and expressed interest in doing a film version. His studio, RKO bought the film rights for

$10,000 where several screen writers took unsuccessful cracks at the

story. With Grant moving on to other

projects like I Was a Male War Bride, the studio was more than happy to sell

it to Liberty Pictures for what it had paid and expressed interest in

distributing the film if Capra directed.

Capra

wanted to direct all right. Working with

a team of script writers he whipped the screenplay into shape—something darker than his pre-war films although both Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

and especially Meet John Doe had despairing moments but that ultimately affirmed humanity.

There

was never a doubt about his lead,

the frustrated small town building and loan operator George

Bailey. Although Henry Fonda may have briefly been

considered, the role went to his close friend

James Stewart. Stewart had been the

boyish idealist in Capra’s most successful film, Mr. Smith and been the straight

man beau in the ensemble screwball

comedy You Can’t Take it With

You. A small town boy himself from Indiana, Pennsylvania who had labored

at his father’s Main Street Hardware

Store before making the break

for college and the daring leap from

there to the New York stage. Capra knew he would totally understand his

character.

|

| Then Major James Stewart with his B-24 crew before a combat mission. War changed the actor. |

Stewart

had also returned from the war deeply changed.

He was visibly aged and much more serious. Although many Hollywood stars served with distinction in the war, none matched

Stewart’s combat record. After being drafted in 1940 as an Army

private after twice being rejected for being underweight, he managed to

talk his way into the Air Corp because he was a licensed pilot. Like other

stars he was first used stateside as

a flying instructor and used in recruiting.

Once again he talked his way into combat in Europe as a B-24 pilot.

He rose rapidly in rank and responsibility and completed

more than 20 official missions becoming

a Squadron and the Group commander. As a staff

officer he assigned himself to

probably twice that many missions which were completed unofficially, including

several in which he led critical raids

or flew dangerous pathfinder missions. He may have flown more combat missions than

any other pilot in the 8th Air Force. Stewart was twice awarded the Distinguished

Flying Cross for actions in combat, the Air Medal with three oak

leaf clusters for campaigns participated in, and the French Croix de Guerre.

He was one of the few men to rise from

private to full colonel in the course of the war. Experiences like that will age and change a

man.

After

taking some time off to decompress from

his harrowing experiences, Capra’s

new film, now re-titled It’s A Wonderful Life marked

Stewart's first return acting. He was deeply unsure of himself and doubted he either could resurrect his acting career of if he wanted to. As a founding

investor in Southwest Airlines

he had seriously considered throwing

everything over to become the infant

airline’s chief pilot. As filming commenced he was suffering

full scale post-traumatic stress syndrome fighting feeling of disorientation, rage, and self-loathing. A large part of his healing was channeling

all of that into his character of George Baily.

Always a fine, natural actor, Stewart was now doing much deeper work

than he had in his pre-war years and it would open the door to more mature

and challenging roles with other

directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Anthony Mann.

Some

were worried that Stewart would not be able to convincingly play the youthful

George Bailey, yearning to “shake the

dust” of the small town off his feet and who instead fall stupidly in love with the sweetly

perfect home town girl. But Stewart

showed an uncanny ability to evoke for audience the shy, stammering youth of his early

films. They literally suspended disbelief

to embrace the middle aged actor as restless

young man. Stewart would continue to

be able to do that even as he aged as he demonstrated

when he played boyish Charles

Lindbergh in The Spirit of St. Louis in 1957 and especially in John Huston’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance in 1962 when both he and John Wayne had to recapitulate their youthful archetypes.

If

Stewart was the obvious choice to play George Bailey, Capra’s reliable favorite lead actress Jean Arthur was

a natural choice. She had been paired with Stewart in both of his

previous Capra outings and she was interested

in doing the picture despite having virtually retired from film work after

her Columbia Pictures contract

expired in late 1944. She wanted to work

again with Capra, but was committed to the Broadway production of Born

Yesterday which was in rehearsals

and out of town tryouts. However she succumbed to increasingly

crippling stage fright and dropped

out of that project opening the door for Judy Holiday. But by that

time the part of Mary Bailey had been cast and the film was in production.

Capra’s

other favorite actress, Barbara Stanwyck,

had already transitioned into playing middle

age and matronly parts and was considered

too old for the part although she was Arthur’s contemporary. A string of top actresses were considered and

Capra approached and was turned down by Olivia de Havilland, Martha

Scott, Ann Dvorak, and Ginger Rogers mostly because the part

was so small and because, as Rogers said in her memoirs because it was “to

bland.” In the end Capra turned to a younger, rising actress—Donna Reed

who had attracted attention as the brave

nurse in They Were Expendable and as Mickey Rooney’s sister, a wholesome

small town girl, in The Human Comedy. She was also a girl-next-door favorite pin-up

of GIs during the war. This film would make her a real star.

It

seemed like every older character actor

in Hollywood, especially those who played heavies

was considered for sour Old Man

Potter. Edward Arnold who had

appeared in both Mr. Smith and You Can’t Take it With You was one

obvious choice. Others were Charles Bickford, Edgar Buchanan, Louis

Calhern, Victor Jory, Raymond Massey, Vincent Price, and even Thomas Mitchell. Lionel

Barrymore, despite having starred in You

Can’t Take it With You for Capra, was not an immediately obvious

choice. In recent years his screen

persona had largely been avuncular,

kindly men like his Dr. Gillespie in

the successful Dr. Kildare movie franchise.

What finally sold Capra on Barrymore

was his annual radio turns as Scrooge in A Christmas Carrol. Barrymore

could play a mean man, even one with

no hint of a lurking heart of gold.

|

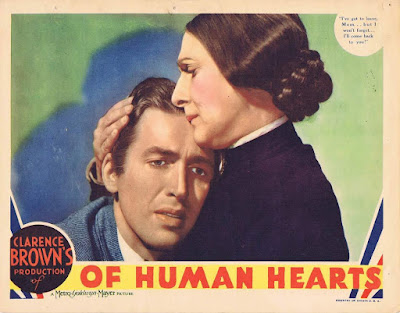

| Bulah Bondi has played the long suffering mother of ungrateful James Stewart in the tear-jerker Of Human Hearts. |

Thomas

Mitchel may not have made the cut playing against type as the villain America’s favorite and probably busiest

character actor fit the role of gentle, addled, and pixilated Uncle Billy like a glove. Beulah

Bondi, who by the way was a graduate

of my alma mater, Shimer back when it was a female seminary, was one of the movies’ busiest mothers when she wasn’t playing spinster school teachers. In fact she had already played mother to Stewart’s

ungrateful and neglectful son in the tear

jerker Of Human Hearts and was Ma Smith in Mr. Smith.

|

| Henry Travers as Angle Second Class Clarence Oddbody. |

Mitchel

was also briefly considered to play Clarence

Oddbody, the Angel Second Class assigned

to George’s case. But the role went to Henry

Travers, a veteran English stage actor who found a second career in American films playing kindly but slightly

befuddled old men. He had received an

Academy Award nomination for his part as the rose-loving gardener in Mrs. Miniver and had just finished The

Bells of St. Mary’s with Bing Crosby and Ingrid Bergman as the unwitting

donor of a new school building.

Silent

film star H. B. Warner, best known

as Jesus Christ in Cecil B. DeMille’s King of Kings, had already appeared in five Capra flicks when he was tapped to play Mr. Growler, the pharmacist who employed twelve year old George Bailey. Several other members of Capra’s informal stock company also had roles.

|

| Gloria Grahame would go from the soiled dove of It's a Wonderful Life, to the fatal temptress in a parade of film noirs. |

Small

town vamp and fallen woman Violet Bick was played by 23 year old Gloria Grahame near the start of her

film career. She would go on to be the queen of film noir temptresses and

bad girls.

The

rest of the company was sprinkled with interesting

and accomplished performers. Ward

Bond and Frank Faylen played Burt the cop and Ernie the cabdriver—and yes those character names inspired the Sesame

Street puppets. Others of note

include Sheldon Leonard as Nick the Bartender, Moroni Olson as the

voice of the Senior Angel who narrates

George’ life story, and even a brief appearance of Carl “Alfalfa” Switzer as Freddie,

Mary’s annoying high school suitor.

All

in all it was a strong an ensemble cast as was ever assembled.

If

the film was costly due to the cost of the cast and the sets—especially the

three-block-long downtown Bedford Falls with

75 stores and buildings, the long center boulevard through which a

desperate George ran planted with 30 mature

oak trees, and a separate residential

neighborhood—at least Capra, always an efficient director, was able to

finish principle shooting between April 15, 1946 and July 27, exactly the 90

day schedule.

During

the filming Capra continued to tinker with the script, shooting and then

junking different versions of how George’s little brother Harry fell through the ice and of the famous climatic scene. He scrapped a version with George falling to his knees in prayer as unnecessarily over the top.

The

finished film was an obvious nod to

the Dickens classic that had inspired the original story writer. But where Scrooge was a bad man with a hardened

heart who had to be terrified into

unlocking a kernel of long buried kindness

and letting it flourish, George

Bailey was a deeply frustrated man

who repeatedly makes good choices

when he must but barely contains seething resentment who

must be shown that his own life was

worth living. This was subtle stuff and far beyond the usual black and white morality of most

Hollywood fare. Those who accuse Capra

of over sentimentality in this film or

glossing over the stultifying drabness and rigid conformity of the small town

George always wanted to leave

overlook the real anguish that

underlines it.

It’s

a Wonderful Life went into general release on January 7, 1947 and was 26th out of more than

400 features that year in revenue, one

place ahead of another Christmas film, Miracle on 34th Street which was

released late that year. Not nearly as

bad as legend would have it.

Despite the accolades the film received it might have faded in the public memory.

In subsequent years Miracle on 34th

Street and the 1938 and 1951 versions of A Christmas Carrol usually let the lists of favorite holiday

films. Capra’s work could easily have

sunk to the level of say Christmas in Connecticut, a film admired by movie buffs but below the

radar of casual viewers.

What saved it from that fate was one

of the most spectacular and inexplicable business blunders in film history.

Liberty Pictures went belly-up after completing just two

films, the second being Capra’s State of the Union with Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn. It’s two

movie film library and other assets were purchased by Columbia Picture and then

repeatedly re-sold to a bewildering succession of companies. In 1955 it was bought by a little known investment outfit called M. & A. Alexander which sold the copyright to the original nitrate film elements, music score, and the film rights to the story on The Greatest Gift as well a television

syndication rights to National

Telefilm Associates (NTA), syndication specialist.

In 1974 a nameless functionary at

NTA flubbed the copyright renewal of the film’s visual images and it passed

into public domain. Anyone could broadcast or reproduce the

film on other media without having to pay syndication

fees or royalties on the film, although they did have to pay royalties for

the story and music which remained under protection. Local

TV stations around the country snapped up the gift from heaven that was plopped

in their laps. Many began annual showings,

often multiple showings. In some markets every station aired the

movie. It was almost impossible to get

through a holiday season without seeing the film. Millions

of Americans and multiple

generations saw the film and fell in love.

In the 1980’s with the rapid spread of home VCRs several companies released tapes of the film, many of them very muddy and poor quality. These included colorized versions denounced by both Cara and James Stewart.

In 1993, Republic Pictures, which was a successor to NTA, regained

protection after a prolonged legal

battle relied based on a 1990 a Supreme

Court ruling in Stewart v. Abend, which involved another Stewart film, Rear

Window) to enforce its claim to the copyright. While the film’s

copyright had not been renewed, Republic still owned the film rights to The Greatest Gift protecting its status

as a derivative work still under copyright.

|

| Is there ever a dry eye in the living room when the bell on the Christmas tree rings and the whole town sings Auld Lang Syne to George and his family? I didn't think so... |

Although the film disappeared from

local television re-broadcasts, since 1996 Paramount,

which now owns the rights to the Republic library, has licensed rights to NBC which

shows the film to wide audiences

twice during each holiday season.

Pull

out the hankies and fill the popcorn bowls. It’s A

Wonderful Life will soon be on your home

flat screen TV again.

No comments:

Post a Comment