|

| Cisco Houston in a professional head shot glossy from the 1950's/ |

He

should have been way more famous. Instead Cisco

Houston is known only among the hardest

core of older folk music devotees

and as an historical footnote—Woody Guthrie’s closest friend and running buddy. But Houston

not only had a phenomenally wide and

varied repertoire of folk songs

that documented the American experience

and working life and a rich baritone that some folks thought

was too good for folk music, but he

was movie star handsome. Maybe his early death at age 42 in 1961 just as the second folk revival was gathering

steam deprived him of the opportunity

to shine for the legions of younger

fans.

Gilbert Vandine Houston was born on

August 18, 1918 in Wilmington, Delaware

where his father was a tin knocker—a

sheet metal worker. He was the second of four children. He was still in school when the family moved

across country and took up residence in Eagle

Rock, a Los Angeles suburb.

Young

Gil was recognized as a very bright

student despite a serious disability—nystagmus or dancing eyes, a condition of rapid involuntary movement of the eyes which reduced his vision and made him rely mostly on his peripheral

vision which greatly affected his ability

to read. He still got top grades by keenly paying attention to class room discussion and absorbing it. It made him an audial learner, a perfect

skill set for a man who became noted for being able to absorb songs like a sponge.

His

supportive family may have read to

him, because he gained a school reputation for being exceptionally well read.

Eventually he trained himself

to use his limited vision to the best of

his ability and did become a devoted

reader.

Gil

also picked up the guitar and a love

of singing from his family from whom he also learned many folk songs.

The

Great Depression hit the family hard. After extended unemployment, his father left

the family in pursuit of a job and virtually

disappeared. Young Gil was forced to

quit school and find what work he

could to support the family. From 1932

at the age of 14 he took whatever he could find.

A

couple of years later he and his brother Slim

hit the road themselves becoming part of a generation of young men forced into the Hobo jungles and the constant

chase after the mere rumor of work.

They roamed the Western states

hopping freights or hitch hiking until they got separated. He worked in migrant farm camps, on construction projects, as a pearl diver—dishwasher, day laborer, and even despite his vision

problems as a cowboy.

Gil

traveled with a battered guitar

strapped to his back and entertained his

fellow wanderers around camp fires

and picked up spare change busking or by plopping down in a corner of a saloon

or café and starting to

sing. He also picked up scores, maybe

hundreds, of songs on his travels, especially cowboy and hobo tunes.

It

was during these years that he picked up

the nickname Cisco. It came not, as

would later be reported, from San

Francisco or because of his supposed

resemblance to the Cisco Kid

with his dark brown hair and the pencil moustache that he grew. He acquired it from some adventure or misadventure in the small town of Cisco, California near the Nevada border in the old Placer County mining district.

By

the late 30’s Houston’s music began to become a more reliable source of income that casual labor. He began to

pick up bookings for pay at saloons

and clubs riding the popularity of cowboy music. In 1938 at age 20 with years of hard

traveling already behind him, Houston returned to Los Angeles to seriously pursue a career as a performer.

Not

only did Houston pick up fairly steady work in area clubs, but he was

encouraged to use his good looks to explore

acting.

He picked up extra work and

uncredited walk-ons and non-speaking parts, mostly at the poverty row studios that specialized in

two-reel oaters. He was befriended by an older actor and folk singer

named Will Geer. Geer was also a committed radical and drew Houston into his

circle of union organizers, rabble rousers,

and Communists. Given Houston’s working class background and life

experiences, he became an eager

recruit.

One

day Geer brought Houston with him to visit another friend, Woody Guthrie, at the KFVD

studio of his cowboy music radio

show Woody and Lefty Lou. The

connection was almost immediate. Guthrie took to the younger man. Their personalities

were different, but complimentary. Guthrie was often effusive and animated

nearly to the point mania, always eager to sing for anyone, anywhere at

the drop of a hat, but also

sometimes moody and subject to black depressions. Cisco was quiet and reserved, more than a little shy. Always more of a listener than a talker. But he had a natural cheerfulness and open

good nature that no amount of the many curve

balls life had thrown at him could discourage.

Soon

the three of them, Geer, Guthrie, and Houston were playing shows at migrant

camps, rallies, and at union hall benefits. They performed a mix of cowboy and hillbilly music, Guthrie’s Dust Bowl songs, and pointed, topical ballads including

rousing union songs. When Guthrie lost his radio show, he and

Houston went even farther afield. They

parted ways for a while when Guthrie briefly returned to Texas to be re-united with his wife

and children.

Then

Geer famously invited both of them to join

him in New York. Both men dropped what they were doing—which

wasn’t much—and made a bee line east. Guthrie held up in Geer’s apartment and

Houston found accommodations,

eventually with Huddie

Leadbetter—Leadbelly—and his wife. From there things would start percolating.

|

| Singing with the Almanacs--Bess Lomax Hawes, Cisco, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and Sis Cunningham. |

Once again Geer introduced his friends to his wide circle of activist and performing friends. After informal living-room gatherings some of them began to perform together as the Almanac Singers mostly at union halls and at events and benefits for various left organizations. The Almanac were less a well defined group than a loose collective of singers which presented themselves in various combinations depending on who was available. Core members included Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, Millard Lampell, Bess Lomax, and Sis Cunningham. In addition to Houston others who occasionally performed with the Almanacs included Burl Ives, Sonny Terry, and Josh White among others.

The

Almanac repertoire included a number

of union songs and pacifist songs by

Guthrie and Seeger which reflected the Communist

line after the Hitler-Stalin

Pact. They were just getting established when Houston signed on with the Merchant Marine in 1940, disguising his visions problems that

should have disqualified him. That meant he missed the recording sessions for the Almanac’s 78 rpm album Meet John Doe which featured anti-war and anti-draft

songs.

But

just as the album came out in June

of 1941 Hitler attacked the Soviet Union and there was a mad scramble to recall the records and destroy

the undistributed copies. Seeger and

Guthrie went into overtime writing new songs urging entry into the fight

against fascism including Guthrie’s The Good Ruben James, a ballad about the sinking of an American

merchant ship by a German U-boat

which also spurred enlistment in the Merchant Marine.

|

| Shipmates Cisco Houston, Woody Guthrie, and Jim Longhi sing for their fellow seamen at the National Maritime Union Hall in New York. |

Meanwhile

Houston was already at sea daring

the horrific losses of the Battle of the Atlantic. He had already survived the sinking of one ship when he came ashore in New York and resumed singing with the Almanacs

between voyages. When the Almanacs broke up in 1943, Houston and his friend Jim Longhi convinced Guthrie to join the Merchant marine with them

while Seeger was drafted and entered

the Army. The three shipped out together three times in convoys on the SS

William B.

Travis, SS William

Floyd,

and SS

Sea Porpoise. The

Travis struck a mine in the Mediterranean Sea and managed to limp to port at Bizerte, Tunisia.

On all three of their voyages together Houston and

Guthrie regularly entertained their shipmates

and played for other crews in port. On

their final voyage in 1944 the Sea Porpoise was carrying 3,000 Troops for the invasion of Normandy. The

pair frequently played more formal deck

concerts for the men on the long and dangerous voyage. The ship was torpedoed by a U-Boat off

of Normandy on June 5. She managed to

make it back to England to be

repaired at Newcastle-upon-Tyne before sailing

back to the States.

It

turned out to be Guthrie’s last voyage—his

seaman’s papers were suddenly yanked for his Communist connections. Houston stayed in the Merchant Marine but

used this time ashore with Guthrie to do his first recordings. At the same famous 1944 recording sessions by Moses “Moe” Asch with Guthrie and Sonny Terry where Woody laid down

many of his most famous songs, including many of the Dust Bowl ballads, Houston

sat in as an accompanist and was

also recorded on his own.

|

| Cisco and Woody recording for Moe Asch in 1944--classic sessions that would be repackaged many times by Folkways and other labels. |

In

the post-war period Houston worked steadily as a musician, studied acting, and began to get stage parts. Most notably he appeared in the 1948 revival of Mark Blitzstein’s ground breaking radical musical The Cradle Will

Rock in a cast that included Will Geer, Alfred Drake, Vivian Vance, and

Jack Albertson directed by Howard Da Silva. Despite the stellar company the revival only ran 34 performances amid revived charges that it was Communist propaganda.

Asch

went on to found Folkways records and in 1948 material

from the sessions began to be released,

helping to spur the post-war or first folk revival. Houston was featured on two of the first releases, including one as

Guthrie’s side man and a collection

of children’s song on Folkway’s Cub Records label, Nursery Rhymes Sung and Played by

Cisco Houston. Folkways would go

on to release several more records over the next decade or so often re-using the same recordings in different

packages. In addition to frequently

appearing on Guthrie recordings and with Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee and others some of his solo recordings included. Cowboy

Ballads (1952), 500 Miles and other Railroad Songs (1953),

Traditional

Songs of the Old West (Stintson, 1954), Hard Travelin’ (1954),

and Cisco

Sings (1958.)

|

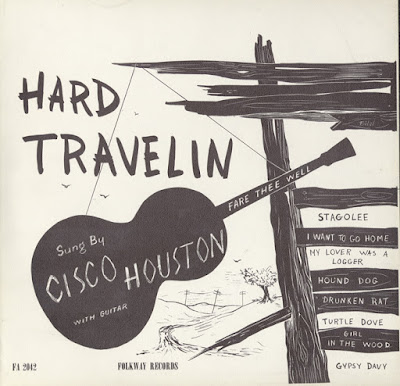

| Houston's 1954 Folkways album. |

These

recording introduced or popularized many

songs that became staples of

folk music including the children’s ditty The Cat Came Back and the bluesy, haunting ballad Five Hundred Miles. These

recordings were for a specialized, limited market of hard core folk music fans and never made Houston much

money. But they did raise his visibility as a performer

and helped him get work.

Through

most of the late ‘40’s and ‘50’s Houston toured as a journeyman musician, making a living but not much more. He never

rose to the fame of old pals Guthrie, Seeger, Hayes, Josh White, Burl Ives,

and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGee although he often shared the stage with all

of them at clubs or concert bookings. He

crisscrossed the country dozens of

times on improvised, self-organized tours. He also made occasional radio appearances.

In

some ways the lack of recognition insulated Houston from the Red Scare era black balling that nearly

destroyed the careers of Seeger,

Hayes and the members of The Weavers. Also, he had never taken a CP party card. That is, he thought he had escaped the worst until just when it looked like his

career might take off.

In

1954 Houston was hired to host a radio

folk music program based in Denver,

Colorado which was syndicated to

more than 50 stations by the Mutual

Broadcasting System. It was billed

as the Gil Houston Show under his original name. This was likely a ploy by the station to obscure

his identity as Cisco and his known

associations. If so, the ruse might not have worked. Despite good

ratings the show was abruptly cancelled after less than a year on the

air. Houston and his friends suspected

the Black List might have caught up to him.

Houston

was briefly married twice. Virtually

nothing is known about either spouse and he had no known children. But his

good looks and quiet charm appealed to

many women and he was known to have had many, usually brief, affairs.

After

the failure of the radio show, Houston shifted his base of operations back to

California, from which he had been mostly absent for almost 20 years. He continued to record for Folkways and for

other small labels and appeared where he could in clubs, on college campuses, and even church basement coffee houses.

Then,

starting in 1958 his long years of struggle seemed to be turning around with the rise of the second Folk

Revival. He was signed to a new, commercial label Vanguard which released his successful

LP The Cisco Special and a follow-up, Songs of Woody Guthrie. He rapidly gained the reputation as the leading interpreter of

his old friend’s songs just as the ailing

Guthrie, no longer able to perform,

was becoming an icon of the new folk

scene.

Although

he was getting better bookings at larger venues, Houston was beginning to

rub up against the reverse snobbery of the folk music

community. Some critics charged that his

rich baritone voice was too polished

to be authentic—a holy term often used to denote raw and off-key screeching. Houston

complained to an interviewer:

There’s always a

form of theater that things take; even back in the Ozarks, as far as you want

to go. People gravitate to the best singer...We have people today who go just

the other way, and I don't agree with them. Some of our folksong exponents seem

to think you have to go way back in the hills and drag out the worst singer in

the world before it’s authentic. Now, this is nonsense...Just because he’s old and

got three arthritic fingers and two strings left on the banjo doesn’t prove

anything.

A

new crop of younger performers, however, were taking note of Houston and he became, at barely 40 years old

himself, a mentor and inspiration to several of them.

The

Black List was fading rapidly. So fast that in 1959 the State Department asked Houston along with Sonny Terry and Brownie

McGee to do a tour of India.

On the way back Houston stopped to play, and even to record some

sides, in Paris, and sing in England.

|

| Cisco Houston with Molly Scott on the CBS TV special Folk Song, USA before his terminal cancer had been diagnosed. |

On

his return in 1960 CBS TV made him

the host of a special, Folk Song, USA which featured Joan Baez, John Lee Hooker, Flatt and

Scruggs, and others. He got great

reviews as a warm and authoritative host. The early summer special was a pilot of sorts for a folk music series. That same summer Houston headlined, at the invitation of co-founder Pete Seeger, at the Newport

Jazz Festival.

Folk

music, and it seemed Houston himself, were poised

to take off and become the next big thing in American culture. But

shortly after the Newport appearance Houston was diagnosed with stomach

cancer. It had already metastasized and he was told that it

was fatal.

Knowing

that he had only a few months to live,

Houston chose to keep doing what he loved and what gave meaning to his

life—performing despite, toward the end, being in constant pain. The illness took a toll on the once strapping

and robust body of a man who had

spent much of his life doing hard physical labor.

Houston

also returned to the studio to record one last album for Vanguard. He completed the final sessions of Ain’t

Got No Home weeks before he died.

In

a letter quoted in a memorial article

in the folk music magazine Come For to Sing by Lee Hays,

Houston wrote:

If you know my

situation, which is a matter of weeks, of months at the outside, before the

wheel runs off... well, nobody likes to run out of time. But it’s not nearly

the tragedy of Hiroshima or the millions of people blown to hell in the war,

that could have been avoided. These are real tragedies.....

Houston

died in San Bernardino, California on

April 28, 1961 at the age of only 42.

He

was widely mourned in the tight knit

community of fold performers even if still not widely known to the public. Tributes poured in. Tom

Paxton, Peter LaFarge, and Tom

McGrath all wrote songs in tribute. Bob Dylan could not fail to mention him

in his Song to Woody just as Peter

Yarrow did in his salute to Josh White, Goodbye Josh.

Smithsonian/Folkways has re-packaged

much of Houston’s work on Folkways and also issued a complete multi-CD edition of the Ache Sessions with Woody Guthrie.

There is also a compilation

of his Vanguard recordings but Cisco

Houston Sings the Songs of Woody Guthrie is the only one of his several

LP’s now available on CD. He also crops up

on recordings with Leadbelly and with Sonny Terry as well as several folk anthologies.

No

known film footage has ever been

found of Houston performing and even still

photos are somewhat scarce. But mostly he lives on as a semi-legendary character in a semi-mythical version of Woody Guthrie’s

life. Woody himself made Cisco

Houston one of the few characters

identified by his real name in his highly

fictionalized autobiography Bound for Glory. Their Merchant Marine pal Jim Longhi

wrote about their experiences in his memoirs

Woody, Cisco and Me: Seamen Three in the

Merchant Marine. And Houston shows

up in several plays and musical reviews about Woody. In the mind’s

eye, they are always singing together in some seedy saloon, killing time

before catching a fast freight together

for some distant job.

No comments:

Post a Comment