On September 17, 1683 Antonie van Leeuwenhoek wrote a letter

to the Royal Society in London describing animalcules—tiny one celled

animals invisible to the naked eye now known as protozoa. In doing so he inadvertently founded a new branch of science—microbiology.

Leeuwenhoek was an unlikely scientist. At the time most scientific investigation was

the sole providence of gentlemen who

had the education, leisure time for investigation, and the fortune

to support the cost of their work.

He was neither a gentleman or particularly well educated. He came from a family of tradesmen or what the English called skilled mechanics. His father was a basket maker and his mother’s

family were brewers. They were from Delft, a reasonably prosperous small

city in the Netherlands province

of South Holland.

As a young man Leeuwenhoek became a draper.

He also worked as a surveyor,

wine assayer and as a municipal official. His occupations made him comfortable, if not wealthy and he was a respected member of the

community. He was friends with and almost the exact

contemporary of Delft’s most famous

resident the painter Johannes

Vermeer and was an executor of

his estate when the master died in

poverty in 1675.

His commercial success allowed Leeuwenhoek the time to pursue his

growing interest in science. An avid

reader, he had read Robert Hooke’s illustrated

book Micrographia.

Hook was working with primitive compound

microscopes using two lenses. But the technology

of he these devises was primitive and could only magnify objects 20 to 30 times.

Around the mid-1660’s he began to grind

lenses in an attempt to create more

effective instruments.

My high school science text credited Leeuwenhoek as the inventor of

the microscope. As you can see, he was

not. Compound microscopes had been

around for nearly 40 years. His devices

had single lenses, but the quality

of the lenses was so high that he was able to achieve documented magnification

of over 200 times. And evidence from his

detailed observations indicates that

some of the devices that he constructed may have neared a power of 500.

Leeuwenhoek’s breakthrough—and a closely

guarded secret in his life time—was not discovered until 1957 when

scientists discovered that he used finely

drawn thread of molten glass to create perfect

small spheres which became his lenses.

The small lens would be set in a brass

or silver plate in front of which

would be a pointed rod on an adjustable screw which would hold the

object being studied. Leeuwenhoek,

working in the brightest natural light,

would hold the devise close to his eye.

Leeuwenhoek constructed at least 500

different devices, only a handful of which still survive. He often crafted new microscopes specifically

for the specimens he wished to examine.

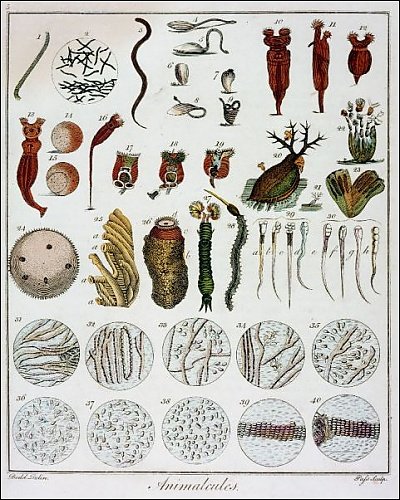

He made careful, extraordinarily detailed written observations of what he saw. These observations are so clear modern scientists can often identify the exact species of microbe he was observing. Since his drawing skills were poor, he later also hired a professional illustrator to make drawings to be enclosed in his letters to the Royal Society and other scientists.

His correspondence with the Royal

Society continued for more than 50 years through his final illnesses. The Society

frequently published his findings translated from Dutch to English or Latin in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, the most

important scientific journal in the world at the time.

Among his

main discoveries were infusoria, the unicellular animals in pond

water now mostly classified as protists; bacteria from the human

mouth; vacuoles, important structures in the cells of plants,

fungi, and some protia; spermatozoa; the banded structure

of mussel fiber; and the blood flow in capillaries.

Leeuwenhoek commissioned a professional artist to illustrate many of his observations for the Royal Society including these animalcules.

In his

later years Leeuwenhoek was famous. He was visited by William of Orange and other notables

who he let make their own observations with his equipment. He even presented a microscope to Peter the Great of Russia when he was invited to visit the Tsar’s ship.

Active to the end, he died in Delft

in 1723 at the age of 90.

In 1981 Leeuwenhoek’s original specimens, sent to the Royal

Society were discovered in a remarkable state

of preservation along with many of his hand written notes in Dutch.

His life and work is a testament to

the talent and persistence of a common

craftsman.

No comments:

Post a Comment