One

hundred and five years ago on November 19, 1915 Utah authorities took Joe

Hill from his prison cell, tied

him to a straight back chair, blindfolded him and pinned a paper heart on his chest. Then, in accordance with the local custom a firing squad of five men, four of them with live rounds in their rifles and

one with a blank, perforated that paper valentine.

No

one was better at setting words to popular or sacred songs for use in educating

and rousing up workers than Joseph Hillstrom, a Swedish immigrant who drifted into the migratory labor life of the American West shortly after the dawn of the 20th Century. He was born as Joel

Hägglund in

Gävle, Sweden

and immigrated to the U.S. under the name Hillstrom in 1902

learning English in New York and staying for a while in Cleveland, Ohio before drifting West.

He

joined the Industrial Workers of the

World (IWW) in 1910 and was soon

sending songs to IWW newspapers,

including his most famous composition,

The

Preacher and the Slave, meant to be sung to the music of the Salvation Army bands who were

frequently sent to street corners to

drown out Wobbly soapbox orators.

As

a footloose Wobbly Hill was likely

to blow into any Western town where

there was a strike or free speech fight. He was a big part of any Little Red Songbook from

1913 on with such contributions as The Tramp, There is Power in the Union,

Casey Jones the Union Scab, Scissor Bill, Mr. Block, and Where the River Frasier Flows. He

also began to compose original music as well, the most famous of which was The

Rebel Girl which he dedicated to the teen-age organizer of Eastern

mill girls, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn.

Hill also dispatched caustic, if crude, cartoons to Industrial Solidarity, the union’s newspaper, some of which ended up on silent agitators—stickers meant to slapped up in mess halls, in lumber camps, in city flops and beaneries, and even on the factory floor.

Joe Hill in a photo taken in prison awaiting his execution.Joe

Hill was often the first fellow worker

ready to take the stump at a free

speech fight and the first arrested. He was loved by his fellow working stiffs and feared as an enormous pain in the side of Western bosses.

Hill

came to Salt Lake City where the

local copper barons feared he might bring

their miners out on strike. The small

IWW miner’s local there was a target of police harassment. But Hill

apparently had no specific plans and

was just booming around looking for

work and possibly a place to winter over

with sympathetic local Swedes.

After

he showed up at a doctor’s office

with a bullet wound, he was arrested and charged with the robbery

and murder of a grocer, a former policeman named

Morrison—and his son the night before. He told police that a woman’s honor was involved and would say no more. He was tried, convicted, and executed by

firing squad in 1915. He was just 36

years old.

Most scholars

agree that it was physically impossible for him to have been involved in

the robbery or to be shot by the grocer.

But questions always lingered about the bullet wound and that vague

alibi.

William M. Adler apparently solved many of the mysteries surrounding Joe Hills life and death.

Finally

in 2013 writer William M. Adler did remarkable spade work and an exhaustive

investigation of Hill time in Salt Lake in his book The Man Who Never Died, The Life, Times, and Legacy of Joe

Hill, American Labor Icon. Adler identified the likely real murder

of grocery store owner and his son as Magnus Olson, a career criminal with a long record who was known to be in the

area and who had beef with the former policeman. The police had even picked him up as a

possible suspect but he talked his way out of it and hid his identity

under a welter of aliases. Olson

also matched the physical description of the assailant given by

Morrison’s surviving son, which Hill did not.

Then Adler identified the mysterious woman—20 year old Hilda

Ericson, the daughter of the family which ran

the rooming house in suburban

Murray where he was staying. She had been engaged to Hill’s friend,

fellow Swede, and Fellow Worker Otto Applequist who also boarded

at the house. Joe won the

girl’s heart and she threw over Applequist for the Wobbly bard. An upset Applequist shot Hill in a fit of

jealousy, but immediately regretted it and was the man who took Joe

to the doctor for treatment. After

taking Hill back to the rooming house he packed his bag and left

at 2 am with the excuse he had gone looking for work. Hill refused to name Applequist out of loyalty

to his friend, and refused to identify the girl to spare her public

humiliation—or perhaps to spare her and her family the risk of

persecution from the police for providing an alibi. And despite all that it cost him, Hill

refused to say more.

The

judgment of history is that Joe Hill

was framed. He became a martyr to labor in no small measure because of his Last

Words, a letter to IWW General Secretary Treasurer William D. “Big

Bill” Haywood,

Goodbye Bill. I die like a true blue

rebel. Don’t waste any time in mourning. Organize... Could you arrange to have

my body hauled to the state line to be buried? I don’t want to be found dead in

Utah.

That

has been shortened as a union motto

to “Don’t Mourn Organize.

He

also composed a memorable Last Will:

My will is

easy to decide,

For there is nothing to divide.

My kin don’t need to fuss and moan,

“Moss does not cling to a rolling stone.”

My body? Oh, if I could choose

I would to ashes it reduce,

And let the merry breezes blow,

My dust to where some flowers grow.

Perhaps some fading flower then

Would come to life and bloom again.

This is my Last and final Will.

Good Luck to All of you,

Joe Hill.

In keeping with Hill’s wishes his body was shipped by rail to Chicago, home of the IWW’s General Headquarters where it was cremated. His funeral was attended by thousands at the Westside Auditorium on Thanksgiving Day where Haywood, spoke along with tributes in several other languages and performances of Hill’s songs. The funeral possession was reportedly one of the largest ever held in Chicago up to that time. It took Hill’s remains to Waldheim Cemetery—now known as Forest Home Cemetery—where the bulk of his ashes were scattered around the Haymarket Martyrs Memorial.

One of the packets of Joe Hill's ashes distributed around the world and to every state but Utah.

The rest of his ashes were divided

into small manila envelopes which

were sent to IWW locals or delegates in all 48 states except Utah as well as to Sweden, and other

countries.

Over the years some packets of Hill’s ashes have surfaced—some that were seized

by the Federal Government in its

1917 nationwide raids on IWW halls

and offices were returned to the union by the National Archives in 1988. The packets have been disposed of in various ways, some ceremonial, some not. British labor singer Billy Bragg reportedly ate some. West coast Wobbly singer Mark Ross has some inside his guitar. Former Industrial

Worker editor Carlos Cortez scattered ashes at the dedication

of a monument to the six striking coal miners killed by Colorado State Police machine gun fire

in the 1927 Columbine Mine Massacre. An urn

kept at General Headquarters in Chicago contains his last known ashes. .

Hill entered American culture as a folk hero along with the likes of John Henry and Casey Jones largely thanks to the memorable 1936 song I

Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night with lyrics by Alfred Hayes and

music by Earl Robinson. As performed and recorded by the great African-American

actor, activist, and singer Paul

Robeson it became an anthem of

the labor movement and eventually more famous than Hill’s own songs. More than three decades later Joan Baez introduced it to a new

generation of radicals and activists when she sang it at the Woodstock Festival in 1989.

Phil Ochs, one

of the heirs of Hill’s protest bard legacy also wrote and

recorded his own Ballad of Joe Hill complete

with a detailed account of his fate.

Hill is also a revered figure in his native Sweden

where he has been commemorated on postage stamps and where his childhood home is reverently preserved as a museum. In 1971 director Bo Widerberg came to the States to film his Joe Hill. Despite his reputation as the lyrical auteur

of the internationally acclaimed Elvira Madigan, Widerberg botched the job by sacrificing much

of the gritty class war content for a sappy

and unbelievable romance. The film sank like a stone when

released in English in the U.S.

IWW artist Carlos Cortez produced several large format lino-cut hand printed posters of Joe Hill.

But even a bad movie could not erode Hill’s

fame. He has appeared in fiction, poetry, and plays and has inspired several works of art, perhaps most notably in linocut posters hand produced by Wobbly artist, poet, and editor Carlos Cortez.

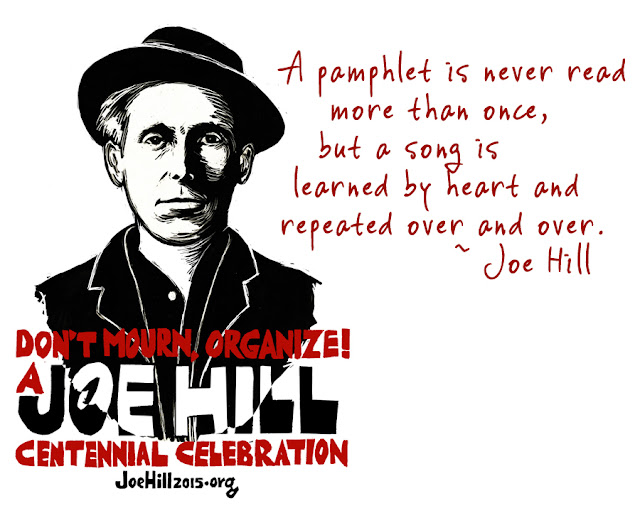

For the centennial of Hill’s execution events

were held around the country and the world all year, including a series of Joe Hill Road Show tours featuring

contemporary IWW musicians and other

performers of people’s music.

Truly, Joe Hill is the Man Who Never Died.

No comments:

Post a Comment