Some

parts of the tale of the so-called Boston Massacre, an iconic moment in pre-Revolutionary Colonial history that used to be familiar to any school child echo in today’s world. All of the ingredients—a rowdy protest boiling spontaneously up from streets where outrage over

long-time grievances sparked into violence over a trivial incident and was met by either firm and appropriate action by

responsible authorities or was a vicious and violent over reaction depending on the political bias of the observer.

And not only was the first victim

a Black man who became a symbol of rebellion but his uniformed killers

were let off virtually scot free at a trial on the flimsiest and

most arcane of grounds. Sounds like the familiar arc of a police

slaying of an unarmed youth, the

kind of all-to-common occurrence that

has fed the Black Lives Matter movement.

It

was a miserable night in Boston in 1770.

What else would you expect on March 5 in the midst of the Little Ice Age which chilled Europe and the Eastern seaboard of North

America for nearly two centuries? A nasty wind whipped across the harbor, a

few flakes of snow would sting exposed fresh. Old snow and ice was pushed up against

buildings turning gray with the soot from

a few thousand hearth fires.

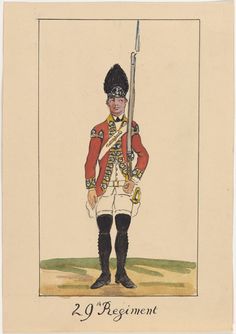

A lone English soldier, Private Hugh White of the 29th

Regiment of Foot had the bad luck

to draw sentry duty outside of the Customs House on King’s Street that night.

The building was a symbol of unfair taxation

without representation and oppression to the people of the city. Customs

collectors had been harassed for

attempting to enforce the unpopular Townsend Duties and for seizing ships of leading merchants like John

Hancock for smuggling, a mainstay of the local economy. The building needed protection.

The

bright red coat of an English private soldier, while colorful, was entirely

unsuitable for the harsh New England winter. Private White undoubtedly shivered in misery. His life was made worse

by the taunting by local toughs, mostly apprentices and day laborers loitering about.

One of them, a wig maker’s

apprentice, Edward Garrick

mocked a passing British officer, Captain-Lieutenant John Goldfinch, for not

paying a bill due his master. Goldfinch ignored the jeers and in fact had settled his account that very afternoon.

But White scolded Garrick for

insulting an officer. The two exchanged heated words. White struck Garrick with the butt of his musket. A small crowd gathered

and began pelting the soldier with snow and ice balls.

When

White leveled his musket against his

taunters, Henry Knox, a corpulent 19

year old bookseller warned him not

to shoot because, “if he fire, he must die.”

White refrained from shooting

but the crowd on the street grew as church

bells rang in alarm. Someone thought to send to nearby barracks for reinforcements for the now besieged White who had retreated to the steps of the Custom House with the door at

his back.

Things

were about to go from bad to worse.

Four regiments of troops were sent to

Boston in 1768, more than were ever stationed there when its very existence was threatened by possible

invasion during the French and

Indian Wars, after the Massachusetts

House of Representatives petitioned the Crown for relief from

the Townsend Duties and circulated

letters of other colonial

legislatures asking for support

in the protest. The Collector of Customs for the Port

of Boston officially asked for troops to protect him after some of his

officers were manhandled and abused.

Four

regiments were dispatched as a show of

force. That was about 4,000 men plus

the wives and children of many of them, officers and enlisted alike, servants, and the inevitable hangers-on to any army. The city of Boston boasted only 16,000 residents and a few thousand more resided in nearby villages. Such a large

force deployed among so few civilians, most of them hostile to their

presence, led to inevitable friction.

Although

two of the regiments had been withdrawn,

soldiers of the remaining two were involved in a number of incidents over that

winter. In addition to hostility to the

policy that dispatched them, minor personal

disputes like the Captain’s late payment to a wig maker, irked the

population. So did the inevitable attention to the local girls by the soldiers, which was often returned by lasses enamored of a dashing uniform.

A serious

bone of contention was the employment of off-duty soldiers at the rope

walk, Boston’s biggest industrial

concern and a main employer of unskilled and casual labor. The soldiers

were working for less than locals and costing many of them jobs. Wives

of several soldiers publicly scolded colonists.

That very afternoon one had promised that the troops would wet their bayonets on trouble makers.

Back

at the Customs House, White was finally relieved

by a corporal and six private soldiers under the personal command of Captain

Thomas Preston, the officer of the

watch who declined to trust a junior

lieutenant with the sensitive

assignment. As they drew close to

the Customs House where the angry crowd had grown to over a hundred, Knox again

warned the Captain of the awful

consequences if his men fired.

Preston reportedly told him, “I am aware of it.”

Once

at the Customs House Preston had his men load

and prime their muskets and form

a semi-circle in front of Private

White and the door. They faced a crowd

now swollen by further reinforcements, many of them armed with cudgels and brick bats. In the very

front of the mob, just feet away from Captain Preston who took up a position in

front of his men, was a dark skinned man

named Crispus Attucks.

Not

much is known about Attucks, not even whether he was a slave, an escaped slave,

or a freeman. He worked as a sailor on coastal traders and

on the docks. He was described as mulato but was known to have

both African and Native American Wampanoag

ancestry. Although there were not many

Blacks in Boston, their presence was not that unusual. They mixed casually and freely with the lowest

classes of White Bostonians—the day laborers, indentured servants, and apprentice boys.

As

Attucks and the crowd pressed forward, Preston had his men level their muskets

but ordered them to hold their fire. He ordered the mob to disperse. They responded

with taunts of “go ahead and fire.”

Preston said that the troops would not fire “except on his order” and made

the point of standing in front of

his men’s guns.

From

out of the crowd someone hit Private Hugh Montgomery in the arm with

a clump of ice or in other accounts he was struck by a cudgel. Montgomery fell to the ground, although he

may simply have lost his footing on the ice, and lost his musket. He grabbed the gun and scrambled to his feet. Enraged, he leveled his gun at the nearest

man, Atticus and fired yelling “Damn you, fire!” to his fellow soldiers.

Attkus

crumpled to the ground mortally wounded. There was a pause of a few seconds and then a

ragged, un-coordinated volley went

off from the troops. The only command

Preston gave was a desperate order to cease

fire.

Eleven

men were hit by fire indicating that some may have been injured by the same

round or that some soldiers had time to

re-load and fire. In addition to Attkus rope maker Samuel Gray and mariner James

Caldwel died on the cobblestones.

Seventeen year old ivory turner

apprentice Samuel Maverick

standing near the rear of the crowd was struck by a ricocheting fragment and died a few hours later. Patrick Carr, an Irish immigrant died of his wounds two weeks later.

The

crowd retreated to near-by streets

but continued to grow. Preston called

out the entire regiment for protection and withdrew his squad to the barracks.

An

angry mob descended on the near-by State

House which was ringed with troops for protection. Massachusetts born Acting Governor Thomas Hutchinson tried

to calm the crowd by addressing them from the relative safety of a balcony. He promised a through and prompt investigation. After a few hours the crowd drifted away.

Local malcontents, becoming known

loosely as Patriots, were quick to

use the slaughter to raise a hue and cry against the Townsend Duties and to the

onerous virtual military occupation of their city. Two virtually identical engravings purporting to accurately portray the shooting were rushed

to publication. The most famous, engraved by Paul Revere, the master silver and

coppersmith, iron foundry man, bell caster, and master

of all trades, after a drawing

by Henry Pelham was published in the

Boston

Gazette and then re-issued in sometimes hand colored prints which made Revere and the printer a good

deal of money.

With

public opinion inflamed, the two regiments in the city were withdrawn to Castle William on an island in the harbor. Had they not been, “they would probably be

destroyed by the people—should it be called rebellion, should it incur the loss of our charter, or be the consequence what it would,” according to Secretary of State Andrew Oliver. By May General

Thomas Gage, in command of all troops in the colonies, decided that the

presence of the 29th Regiment was counterproductive

to good order, had the regiment removed from Massachusetts entirely.

Meanwhile

at the end of March Captain Preston, the men in his rescue squad, Pvt. White

and four civilian employees of the Customs House, who some had fired out the windows of the building were indicted for murder and manslaughter.

Gov.

Hutchinson managed by hook or by crook

to delay the start of the trial for nearly a year to let inflamed passions died

down. Patriots took that time to organize

the publication of an account of the

event, A Short Narrative of the Horrid Massacre, which although banned from circulation in the city, inflamed passions across the Colonies, and

even earned sympathy when it was reprinted

in London.

Patriot lawyer John Adams successfully took up the defense of Captain Preston, the accused soldiers, and civilian employees of the Customs House.

Despite

the delay, it looked like it would be very difficult for Captain Preston and

the soldiers to get a fair trial in

Massachusetts. All of the leading local lawyers had refused to

take their cases. John Adams, a leading Patriot, a man with boundless political ambition, and first cousin to rabble-rouser-in-chief Samuel

Adams, agreed to take on the case, despite howls of protest from his political allies.

It

was a great choice. Assisted by his

cousin Josiah Quincy, another

Patriot, and Loyalist Robert Auchmuty

he quickly obtained a not guilty verdict

in the first trial. Captain Preston was shown

by the testimony of multiple witnesses

to have never ordered the troops to fire and to have tried to get them under

control. That was in October.

In

November the cases of the enlisted soldiers proved dicer. They had, after all, fired lethal rounds

without orders. Adam’s pled straight up self-defense. He told the jury that the men were under attack

by the mob, “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes, and molattoes, Irish

teagues and outlandish jack tars.” Appealing

to the class prejudice of the land-owning pool of eligible jurors, Adams won acquittal

on murder charges for all of the defendants, and only two were convicted of manslaughter.

Privates

Montgomery and Kilroy still faced the

death penalty at the sentencing on December 14, they “prayed the benefit of clergy”,

a remnant of Medieval law in which the essentially claimed exemption from punishment on the grounds that they were “clergy”

who could read a Bible verse. The two were branded on

the thumb and released.

By

the time the civilians were up for trial in December, enthusiasm for continuing

the case against them, which was weak and based on the testimony of one servant easily proven to be false, was waning.

Whatever

the outcome of the trials, the

events of March 5 helped set the stage for the American Revolution.

By the way the term Boston Massacre was not applied to the bloody ruckus until long after the fact. Like another iconic event, the so-called Boston Tea Party it got its name during the brief national enthusiasm generated by the 50th anniversaries of important Revolutionary and pre-revolutionary events. And like the Tea Party it was soon imbued with a lot of romantic myth and nonsense.

No comments:

Post a Comment