With

local boosters licking their chops

and a somewhat embarrassed Major League

Baseball trying desperately to hold on to a ridiculous origin legend for the game saddled on them by the Mills Commission of 1908, the National Baseball Hall of Fame opened

its doors in beautiful but un-bustling Cooperstown,

New York on June 12, 1939.

The

pedigree of the National Pastime was

somewhat murky. Everyone knew

that it grew out of ball, bat, and tag games like Rounders

and Townball which had been played

on village greens since at least the

turn of the 19th Century. It was assumed to be related in some way to Cricket, the English national game which began taking hold in big American cities with the establishment

of clubs of well-heeled sportsmen. The

connection to Cricket, and even to Rounders, another game of English origins,

offended the sense of cocky jingoism

that accompanied the coincidental rise of baseball and America as a muscular

new world power in the later half of

the century.

If

the paths of evolution were befogged in the mists of time, the actual beginning

of modern baseball was not, and plenty of people knew it. The game as we know it came into being with

the formation of the New York Knickerbockers

founded on September 23, 1845. It

was one of several amateur sporting clubs made up mostly of young clerks playing bat and ball games to a

variety of rules. Alexander Cartwright and other members hammered out the Knickerbocker Rules, the first ever published. The adoption of these rules by other clubs

made games between squads of rival clubs possible without long negotiations

over field or day rules.

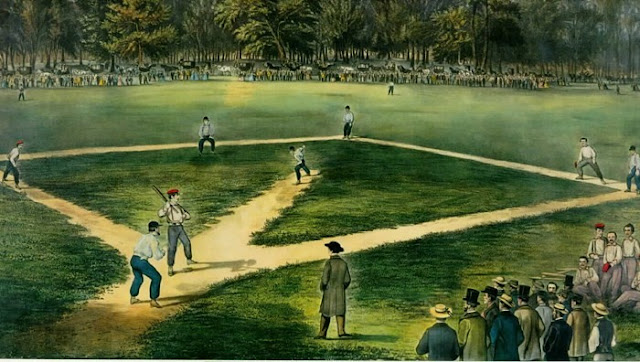

The

first inter-club game under these

rules was played at Elysian Fields

in Hoboken, New Jersey on June 19, 1846.

The Knickerbockers, by the way, lost to a club called the New York Nine. But it was pretty clearly THE first game.

By

the onset of the Civil War baseball

was being played by clubs adopting the rules throughout the Northeast, Mid-West, and Upper South, although various other

versions were still played locally in small towns and villages.

Many

a lad packed his bat and ball with his kit when reporting for duty in the Union Army. Baseball games enlivened

the deadly boredom of camp life between episodes of unimaginable horror

in the big battles of the war.

Young

Abraham Mills—no known relation to

my mother’s family—of the 5th New York

Volunteers—Duryée’s Zouaves—participated

in one notable game on Christmas

Eve of 1862 against members of other regiments before 40,000 troops camped

at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina.

Mills

returned from the war as a second lieutenant, completed law school

and set off on a distinguished career.

But he kept his hand in baseball as the player manager of the amateur

Olympic Base Ball Club in Washington,

D.C. Eventually his legal and

business connections and baseball experience secured him the Presidency of the National League.

In

1908 the former executive was put in charge of a special commission charged

with investigating the origins of the game.

Privately it was understood that he was to discover a uniquely American

pedigree un-besmirched by close association to British games. The Mills Commission did not work very

hard or very diligently.

On

the strength of a claim in one letter from a Colorado mining engineer,

Abner Graves who claimed to have

witnessed the first game played by Abner

Doubleday, a future Union Army general, and students of the Otsego Academy and Green’s Select School in Cooperstown in 1839. Despite numerous inconsistencies in

the story, the Commission declared to the world that Doubleday was the founder

and Cooperstown the cradle of baseball.

That

was their official story, and they were sticking with it, even as mounting

evidence year by year undercut the claim.

Cooperstown

was a once thriving town off the beaten track in central New York State. Near-by Lake

Otsego is the source of the Susquehanna

River. Its other connection to fame

was that it had been platted from a claim by the father of writer James Fenimore Cooper. Once the center of a hops growing region, it had been hit hard first by Prohibition and then by the Depression which had cut deeply into a summer resort business.

Stephen Carlton Clark, whose family had

made a fortune as co-founders of the Singer Sewing Machine Company and who had extensive holding in the

town, including half-empty resort hotels began scheming to find some way to

boost tourism. He realized that the

Doubleday connection was just what he needed.

He

began promoting the idea of a Hall of Fame in his hometown in the mid-1930s. Finally securing the blessing of Major

League Baseball, he launched a well-publicized national campaign to

elect the first members of the Hall while preparing his building in Cooperstown.

On

January 29, 1936 the first “class” was elected

And quite a line-up it was—Ty

Cobb, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson, and Walter

Johnson. With the standards for on field performance—not personal behavior—set so high, no

subsequent class would be admitted without controversy

and argument.

On

the strength of those names, particularly Ruth, who had only recently retired

and was still the Sultan of Swat to

well-heeled Yankee fans for whom the

tedious trip to Cooperstown was not quite so inconvenient, Clark finished his

shrine and launched it to great hoopla.

It

was an even greater goldmine than Clark ever imagined.

Currently

there are 333 elected members of the Hall including former MLB players, Negro leagues (now recognizing those organizations as Big Leagues), managers, umpires, and pioneers, executives, and organizers. In addition sportswriters

and broadcasters are also honored as

are collectively the members of the All-American

Girls Professional Baseball League.

This

year there will be no players voted on by sportswriters inducted for the first

time since 2013. No player quite made

the required cut despite the presence of at least three who would ordinarily be

shoe-ins—pitchers Curt Schilling, Roger Clemens, and intimidating

slugger Barry Bonds. But all of

them, like many top players of their era, have been tainted to one degree or

another steroid use which a significant portion of the baseball

writers currently feel should be disqualifying.

There

will, however, be inductees honored.

2020 additions to the Hall—Derek Jeter, Larry Walker, Ted

Simmons, and the late Marvin Miller, the controversial Executive

Director of the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA)from

1966 to 1982. Believe me, team owners and league executives hate that last selection

and fought it for years. had their ceremonies canceled last summer by

the Coronavirus pandemic.

The

2020 cancelation and the general Covid-19 travel shut down was a huge economic

blow to Cooperstown, the Hall, and the Clark family. With no new inductees the traditional Awards

Presentation will remain an indoor, television-only event, Saturday,

July 24. There will, however, be an induction

ceremony in September with very limited seating at the Clark Sports Center which

has hosted it outside on the lawn since 1992. But far fewer than the usual crowds which approached

or surpassed 50,000 at five of the last six ceremonies from 2014-2019 will be

on hand.

Before

the pandemic about 315,000 fans annually made the still inconvenient pilgrimage

to what is now considered a reverential shrine.

With a full 2021 season reviving enthusiasm for the National Pass

Time, and the public eager to resume traveling, those numbers may well be

exceeded next year.

Decedents of the Clark

family certainly hope so. They still sit

on the Board and own just about all the available accommodations in town. They

are very good at counting money.

Like

a Muslim Hajj, very devoted baseball fan is expected to make the

pilgrimage at least once in his or her lifetime. I haven’t met that holy obligation yet.

Contributions to the cause will be gratefully accepted.

No comments:

Post a Comment