The word to describe Ida B. Wells

was fierce. The word more commonly used, formidable, is entirely inadequate for a life of defiance and struggle that began in slavery during the Civil War and ended just

before the New Deal. Along the way she was the associate or opponent—sometimes both the

with the same person—of Fredrick

Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Francis Willard, Jane Adams, Booker T. Washington,

W.E.B Dubois, Alice Paul, and Marcus

Garvey. She exposed the lynch mobs running rampant in the Jim Crow South, helped found the NAACP and half a dozen other important

organizations, pioneered the Great Migration from the rural South to Chicago and other Northern

industrial cities, and demanded equal voting rights for

women and African-Americans. When she died

it was as if a visceral force of nature had suddenly vanished.

Wells was born in slavery as the

Civil War was rapidly marching

toward the end of servitude on July 16, 1862 on a plantation in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Her parents were among a sort of slave elite, spared the drudgery of

the fields and by in large the lash. Her father, James Wells, was a master carpenter and her mother, Elizabeth “Lizzie” Warrenton Wells, was a prized cook. Both were literate and began to teach their daughter as soon as she was

big enough to hold a book.

After emancipation, James Wells became a known Race Man, a vocal leader

among his people and ambitious for himself, his family, and his race. He managed to attend Shaw University, now

Rust College, in Holly Springs for a while.

He was a leading member of

the local chapter of the Loyalty League,

a kind of Republican Party auxiliary in support of Reconstruction and opposed to the Ku Klux Klan. He spoke

for Republican candidates and

his home was a center for political action,

but he never himself ran for office.

If the family’s politics were firmly Republican, mother Lizzie made sure that young

Ida was brought up in the firm Christian principles of the Baptist faith.

From the beginning she showed a fierce independence and a quick temper at perceived injustices. Her

parents enrolled her at Shaw, but after a few months was expelled for a sharp

exchange with the college president. She was sent to visit her grandmother to cool down while her father tried to mend fences.

Ida’s nurturing and stimulating

home was shattered in 1878 while

on that visit. She got word that her parents and an infant brother were all struck down in a devastating yellow fever epidemic that swept the South.

Orphaned at 16, she resisted

efforts to parcel out five other younger siblings to relatives. She determined

to keep the family together. Ida took a job teaching in segregated

schools, working at a distance from home and coming back on weekends

and holidays while her paternal grandmother cared for the

children. From the beginning she was outraged that as a Black teacher, her salary

was $30 a month, less than half the pay of whites.

After a few years to improve her lot,

she moved with most of her siblings to Memphis, Tennessee, the bustling

economic capitol of the Mississippi

Delta, and the home to a large

and sophisticated Black community. By 1883 she was employed by the Shelby County School District in nearby

Woodstock. During the summers she studied at Fisk

University across the state in Nashville

and she also frequently visited family in Mississippi.

So, Ida was a veteran train rider. She

knew the conditions of segregation in the cars well that had taken quick root after the Supreme

Court had struck down the Civil

Rights Act of 1875 the previous year. That act had banned discrimination on public

accommodations in interstate

commerce—railroads.

On May 4, 1884 Wells was ordered out of her seat by a conductor to make room for a white passenger. She refused

to be relocated to the smoking parlor and had to be dragged from the train by two or three

men. Almost 50 years before Rosa Parks, Ida would not submit so passively to arrest.

Back in Memphis she hired a prominent Black attorney to sue

the railroad and wrote about her experience and cause in

the Black church newspaper The

Living Way. Despite her attorney being bribed by the railroad to sabotage

her case, Wells won a $500 judgment. The state

Supreme Court later overturned the

verdict and ordered her to pay steep

court costs.

But the event made her a hero in the Black community and launched her on a secondary career as a

journalist and crusader. In addition to The Living Way, she was hired

to contribute articles to the Evening

Star. She was an outspoken commenter on race issues while continuing to teach.

In 1889 Rev. R. Nightingale of the Beale

Street Baptist Church invited Wells to become co-owner and editor of

his anti-segregationist newspaper, Free

Speech and Headlight. With the end

of Reconstruction and the dawning of the Jim Crow era violence against

Blacks to “put them back in their place”

was escalating. Wells made a specialty of documenting

outrages.

In March of 1892 the three proprietors of the thriving People’s Grocery Store in

Memphis, which was seen as competition

and an affront to white businesses,

were attacked by a mob and dragged from their store. A crowd

from the community gathered to defend the men and three of the white attackers were shot.

Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart, all personal friends of Wells, were arrested and jailed. A mob

broke into the jail and murdered the men.

Wells had been out of town at the

time of the attack. But she rushed home and began writing furiously. Finally, she concluded that if the leading

businesspeople in the Black community were not safe from lynching nobody was. Sadly

and reluctantly, she advised her readers:

There is, therefore, only one thing left to do; save our

money and leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor

give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold

blood when accused by white persons.

Receiving daily death threats Wells armed herself with a pistol.

Three months after her friends were

lynched a mob attacked and burned the

offices of Free Speech and Headlight.

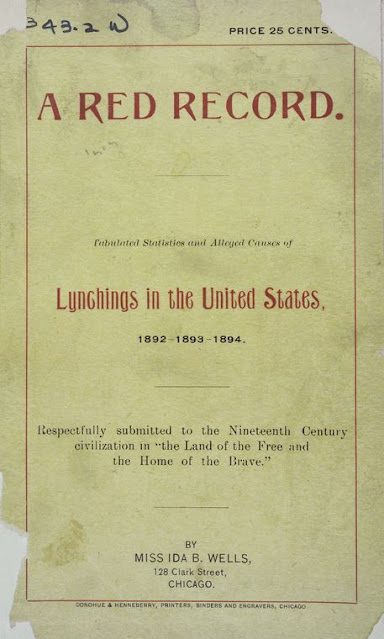

A Red Record, Well’s classic lynching exposé made her famous.

She took up the cause of exposing and fighting lynch law with a

vengeance and unmatched passion. Speaking to women’s clubs around the country about her documented research on how widespread

it had become, Wells raised enough

money to publish a pamphlet, Southern

Horrors: Lynch Laws in All Its Phases. Later she documented the atrocities

in detail in an even more shocking book,

The

Red Record, which made her a celebrity.

Ida also breached the taboo topic of sex, repudiating the popular myth that

many lynchings were to protect pure

white womanhood from predatory Black

males. She documented that most interracial sexual liaisons were not

only voluntary, but were initiated by whites, women as well

as men.

Sooner

rather than later she had to take her own advice. In 1893 she relocated to Chicago, the tip of the

spear of the Great Migration

which would fill northern cities with Southern Blacks. She continued to speak out on lynching and

contributed to black newspapers.

But she did not confine herself to the issue of lynching.

She had been drawn to Chicago by the World

Columbian Exposition. She

was soon collaborating with Fredrick

Douglass in urging a Black boycott of the Fair in protest to discrimination in hiring construction workers and more skilled workers—Blacks were only hired for the most menial tasks and as waiters and porters. She contributed to

the pamphlet, Reasons Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian

Exposition. More than 20,000

copies were circulated to fair visitors.

Wells launched an extensive speaking tour which took her to many

northern cities and to visits to England

to promote her anti-lynching campaign.

She was greeted as a hero in London. She also met

and was impressed by the leading English Suffragettes. While in town

she became embroiled in a bitter public newspaper exchange with

another visiting American reformer, Francis

Willard of the Women’s Christian

Temperance Union who asserted that Blacks were not ready for or

deserving of equality until they gave up drinking, which she said was epidemic. Wells, herself a teetotaler, refuted the charges in none

too temperate language.

In 1895 Wells married the editor of

Chicago’s first major Black newspaper, Chicago

Conservator, Ferdinand L. Barnett. Barnett was also a lawyer and former Assistant

States Attorney. They had met

shortly before her departure from Memphis when Barnett served as her pro bono attorney in a libel case. She became stepmother to his two

children and the devoted couple

had four more. She continued

her public career but frankly sometimes

had difficulty balancing home

and other commitments.

Well’s interest in women’s issues was almost

as strong as her devotion to her race.

She felt the two causes were not only complimentary, but

inseparable. In 1896, Wells founded

the National Association of Colored

Women, and also founded the National

Afro-American Council. She also formed the Women’s Era Club, the first

civic organization for Black women which was later renamed for its founder.

The

latter organization brought her into close

collaboration with Jane Adams

and they jointly campaigned against

the segregation of Chicago Public Schools and on other

reforms.

Her frequent lectures on behalf of universal suffrage attracted the attention and admiration

of the aging founder of the movement, Susan

B. Anthony. When Wells had to dial back some of her commitments for a

while after the birth of her second child, Anthony publicly lamented the loss.

In 1909

she was one of the prominent leaders

to join with W.E.B Dubois,

Mary White Ovington, and others to found the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (NAACP). However, her name was left out

of publicity about the founding and she was one of the few principal founders not to get a prominent office in the new

organization. Dubois claimed that Wells asked not to be

listed, and later corrected the

founding story. Few people, least of all Wells herself who was not one to hide her light under a bushel, believed the story.

There was frankly a kind of

rivalry between two of the best

known and most militant Black

leaders both of whom had risen to prominence as journalists and muckrakers. Despite the snub, Wells remained active in the organization and for his part Dubois

published her articles in The Crisis.

The always outspoken Wells was not afraid of controversy within the Black community

and movement. She was an early and outspoken critic of Booker

T. Washington, the figure often held

up by the white establishment as

the modest model of Black leadership

for demanding few concessions from whites and advocating self-improvement through education.

She also drew the wrath of many black leaders by praising

Marcus Garvey for his message of economic self-sufficiency for Blacks and was one of the few to publicly defend him when he was accused

of mail fraud in a Federal indictment in 1919. Despite the criticisms, her embrace of Pan-Africanism and particularly the Back to Africa aspects of Garvey’s

movement was limited. She preferred

to live and fight in the United States. And after Garvey flirted with an alliance

with the Ku Klux Klan in the early

‘20s so that “each race could flourish,”

she could not stomach further association with anyone who could ally with lynchers.

But

positions like these limited her influence among Black leaders who

hoped to mollify white suspicions. It could crop

up even in organizations that she founded.

She was once denied a speaking role at a convention of the National Association of Colored Women because delegates

feared her radicalism would result in bad

press.

Wells

threw her support to Alice Paul’s

militant faction of the National

American Woman Suffrage Association and with her friend Jane Adams interceded with the conservative national

leadership of the organization to approve

the giant Women’s Suffrage Parade in

Washington, D.C. on the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s inaugural in

1913. She marched with a contingent of Black women.

By the 1920s Wells

was semi-retired from public life, having

given up public lectures and

most organizational duties. She could

still be counted on to fire off a fiery article or editorial when an issue moved her. She mostly

dedicated herself to her husband and family and to meticulous research for an autobiography

she was writing.

Occasionally

she responded like an old fire horse to an alarm.

In 1930, disgusted that neither major party had any program to relieve the great distress in the Black community

caused by the Great Depression, she ran as an independent for a seat in

the Illinois General Assembly. She was one of the first Black women in the

country to run for election at that

level. Of course, she lost.

When Wells died on March 25,1931 at age 68 she was still working on her autobiography, Crusade for Justice. A first edition had been published in 1928, but she was working on a greatly revised and expanded version, backed by meticulous research when she died. As one writer put it “the book ends in the middle of a sentence, in the middle of a word.”

Wells was

widely mourned, especially in Chicago.

She was memorialized most obviously in the massive

Ida B. Wells Homes, a wall of high-rise public housing

along with mid-rises and row houses built by the WPA in 1939-41 for the Chicago Housing Authority. Always intended for Blacks from the slums of the South Side, the Homes deteriorated

into a gang violence ridden symbol of urban failure and

were razed in stages between 2002

and 2011. Most of the residents never new a thing about the

woman the buildings were named for.

Wells’s fame has been surprisingly limited for one so deeply involved in so many

social issues over such a long

and critical time. She mostly gets a footnote mention in histories for her anti-lynching crusades. The academic guardians of American history,

at least as it is presented to impressionable high school and college students, favor far more moderate voices than that of Ida B.

Wells.

Perhaps they are still a little afraid of her after all this time. Certainly not surprising in a country where a third of the voting age population regarded Michelle Obama as a raging radical and America hater.

No comments:

Post a Comment