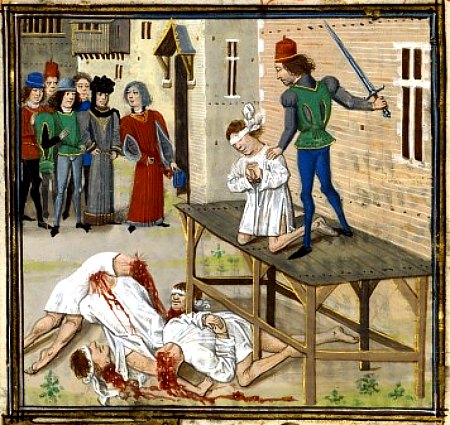

The Lioness of Brittany Jeanne de Belleville was heroically depicted in this illustration from an illuminated manuscript.

There is something about a female pirate that stirs the imagination—and evidently the loins. Googling women pirates turns up a torrent of pictures—heaving breasts straining against thin shirts, hair flowing in the wind, cutlass or pistol held menacingly sometimes with a cringing victim at her feet. There are drawings old and new, woodcut prints, fantasy paintings, and plenty of posed photos, some with even less clothing.

In fact, there were, indeed famous lady buccaneers most famously Grace O’Malley, the Queen of Umaill and Chieftain of the Irish Ó Máille clan of Elizabethan times and several who plied and plundered the Spanish Main including Anne Dieu-le-Veut, Jacquotte Delahaye, and Anne Bonny—all portrayed as fiery red heads a la Maureen O’Hara.

A typical fantasy depiction of a female pirate complete with amble cleavage and fiery red hair.

But none could hold a candle to Jeanne de Clisson, a noble woman of Brittany whose vengeance spawned career on the seas that was un-matched for duration, ferocity, and merciless brutality.

It all began on August 2, 1343 when Olivier de Clisson was found guilty of treason and beheaded at Les Halles in Paris. His seriously aggrieved widow, Jeanne de Clisson, decided to take matters into her own hands the rest is history, grisly history.

Jeanne was born in 1300 to Maurice IV of Belleville-Montaigu, a leading noble of Britany At the age of 12 she was married to another noble lad, 19 year old Geoffrey de Châteaubriant. The marriage produced two children if little passion and ended when Geoffrey up and died leaving a lovely 26 year old widow.

A woman of such high birth, wealth, and beauty was not destined to be a widow long. In 1330 Jeanne married Olivier III de Clisson another nobleman who held a castle at Clisson, a house in Nantes and lands at Blain. Between the two the new husband and wife were instantly among the wealthiest and most influential couples in Brittany. But the marriage also seemed to be particularly loving and close. The two were about the same age and they had five children together—Maurice, Guillaume, Olivier, Isabeau, and Jeanne. The younger Olivier would grow up to be a significant figure in French history on his own and once was Constable of France.

Olivier was a descendent of English knights who were awarded estates in Brittany to help preserve the claim of the English Crown on the province. But by this period, he was a vassal of the King of France, Philip IV. When the Duke of Brittany died leaving no clear heirs each of the two main claimants were backed by opposing sides in the great chess game for control of most of France known as the Hundred Years War. Philip backed Jeanne de Penthievre and Edward III of England put his money on Jean de Montfort.

A depiction of the execution of Oliver de Clisson on the orders of King Phillip IV of France. His widow took vengeance.

Despite his ancestral ties to England, Olivier apparently loyally joined other important nobles including Charles de Blois to defend Brittany from the English and de Montfort in 1342. Unfortunately, in the campaign to follow Olivier failed to hold Vannes, an important port through which the English could land still more troops. De Blois suspected treason in the surrender of the port. When Olivier, blithely unaware, decided to attend a tournament in French territory, he was arrested and hauled to Paris for trial. He was tried before 15 noble peers including his accuser de Blois and the King himself. He was quickly found guilty and had his head separated from his body by an axman. Olivier’s personal holdings were confiscated—much of it ending up in the hands of de Blois. And to add to the ignominy, his severed head was returned to Nantes to be displayed on a pole.

Twice widowed Jeanne did not take this lightly. She sold all of her considerable personal holdings—and according to some accounts by less-than-friendly French chroniclers her 43 year old body—to raise the cash needed to purchase the three largest and newest warships she could find. She hired the best captains and crews—a mix of Bretons, English, and rogue French and armed them well.

To make her ships distinctive and to terrify her enemies, she had them pained black and their sails dyed a deep crimson—itself an expensive proposition. Taking personal command of her fleet Jean began her career as a pirate warring exclusively on French commerce from the refuge of the many often fog enshrouded coves and inlets of the Britany coast. Hunting in a pack or sometimes singly the Black Fleet had no trouble overhauling and capturing the ships of King Philip, his nobles, and wealthy merchants. After boarding the helpless vessels Jeanne was merciless, executing the crew. Her preferred but messy method was to stab them to death with daggers while they were bound and kneeling. Jeanne was said to personally join in the slaughter of the captains and officers. Bodies were unceremoniously dumped overboard. But she was careful always to leave two or three survivors who were put ashore with the instruction to report to the king that Jeanne had struck.

Dozens of ships were captured in this manner and Jeanne’s wealth began to grow. And so did her popularity in Brittany, among the common people and the allies of Jean de Montfort who began to hail her as the Lioness of Brittany.

A woodcut depiction of a ship of the Black Fleet executing the crew of a captured ship.

Since she was careful to leave English shipping undisturbed, Jeanne was effectively the ally of Edward III and her depredations were bound to have an effect on his on-going war with Philip. Not only did she effectively sweep the Channel of French warships, but the supplies she plundered helped sustain the English armies campaigning in France and some historians credit her with thus contributing to the great and legendary English victory at the Battle of Crécy in 1631.

Some thought that Jeanne would end her rampage when Philip died in 1350, his kingdom almost in ruins from defeats by the English and the Black Plague. They were wrong. She turned with new gusto to seeking out the ships of loyal French nobles. When she found one on board she reportedly personally beheaded him with an ax. This was something that even strong men found difficult, so it is likely her victims had to endure being hacked several times before their heads rolled away.

A fanciful contemporary depiction of Jeanne de Clisson in battle.

After thirteen years as the terror of the Channel, Jeanne retired and wed for a third time to Sir Walter Bentley, a lieutenant to Edward III and retired to England with her children including the younger Olivier. Later she returned to France where she lived in luxury in Hennebont until she died in 1359.

Her son, Olivier IV de Clisson, made quite a name for himself with important commands on both sides of the War of Breton Succession, that long-running side show to the Hundred Years War. He was famous for ordering no quarter to his battle captives. The apple, it seems, did not fall far from the tree.

No comments:

Post a Comment