Regular

readers of this blog may have

noticed a recurring interest in innovations in transportation and communications—the

things that have tended to tie together

our shrinking world. But sometimes I am stunned to discover an innovation years—decades—before I

ever suspected. Take the notion of powered flight—the ability to propel

and control some kind of aircraft over a distance by a mechanical

engine. I assumed that it would require some sort of internal combustion engine.

I never even considered the possibility of steam—the engines themselves were heavy and required quantities of water and fuel, not to

mention the inherit dangers of fire, heat, and flying cinders.

So

imagine my astonishment to discover that just such a flight occurred on September 24, 1854 and that powered flight was just one of several innovations.

That

year Henri Giffard was a 27 year old

French engineer. Two years earlier he had his first experience

with lighter than air craft when he collaborated with another engineer named

Jullien to build an airship with a propeller driven by clockwork. That craft had an elongated hydrogen

filled balloon with ends that tapered to points. But the clockwork

propeller could not generate enough

energy to move the balloon very far in perfectly still conditions—or for very long until the engine wound down. It was

also lacked any means of steering or

controlling the movement of the flight. But

the effort had showed that a propeller could indeed, propel if a reliable source of power could be found

to turn it.

In

1851 Giffard patented the “application

of steam in the airship travel” and a year later built a remarkable small engine weighing just 250 pounds

with a boiler and fuel—coke—that added another 150 Lbs. That was light enough that a gas envelope could be built capable of lifting it plus the weight of a single passenger/operator. Giffard

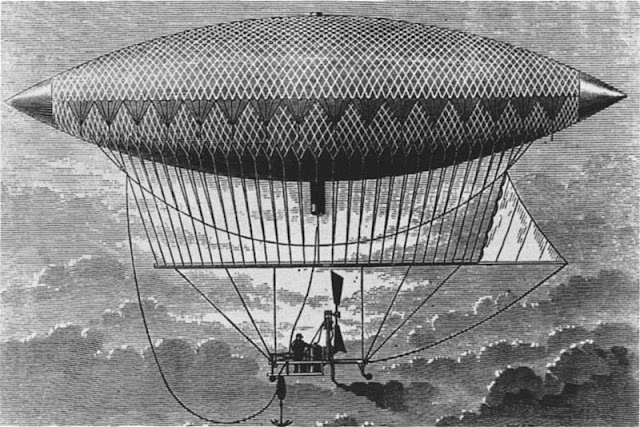

built the first ever true dirigible—a

term derived from a French word meaning steerable.

That meant an airship with a semi-rigid gas envelope as opposed to

an inflatable bag, that could move

under its own power, and that could be maneuvered.

The

engine was just one of Giffard’s innovations.

It produced 2,200 watts or three horsepower to

turn a three-bladed, rear mounted

pusher propeller. To put it in

perspective, that is about the same power as generated by a modern steam iron, but it was

enough. The engine was mounted on a platform along

with the operator which was suspended

from a long beam slung below the 144

foot long envelope. At the rear

of the beam was a moveable triangular

sail that acted as vertical rudder

enabling the aircraft to maneuver.

The trickiest problem was what to do with

the cinders that would inevitably escape the combustion

chamber and rise imperiling the

highly flammable hydrogen in the

envelope. Giffard devised a long exhaust tube that pointed

down and behind the engine

instead of a top mounted smokestack

common in steam engines. That directed

sparks down and away from the envelope and hopefully the forward movement of

the air ship would be fast enough to keep them from rising to the rigid

bag. All in all it was a remarkable

construction.

Giffard

took off from the Paris Hippodrome

and flew 17 miles to Elancourt, near

Trappes in three hours for an average speed of six miles per hour. Along

the way he made several turns and

even flew in short circles to prove

that his ship was controllable. The

original plan was to take on more fuel and water and return to Paris. But Giffard found that his engine was not

powerful enough to move the ship against even a light headwind.

The

Giffard Dirigible never flew again. Attempts to improve on it were stymied by the additional weight of

steam engines powerful enough for practical

use. The future of the Dirigible

had to wait until the development of light and practical engines. In 1872 Paul

Haenlein flew a hot air craft—a blimp—with an internal combustion

engine running on the coal gas used

to inflate the envelope. The La

France was launched for the French

Army by Charles Renard and Arthur Contantin Krebs in 1884

propelled by a battery powered electric

motor. In its maiden five mile flight it became the first airship ever to

complete a round trip.

A hydrogen-lift dirigible powered by the

first use of such an internal combustion engine had to wait until 1888 when Dr. Frederich Wölfert built an airship

powered by Daimler Motoren Gessellschaft

gasoline engines, 36 years after Giffard.

As

for the inventor, he had more innovation in him. In 1858 he invented the injector, a type of pump

that uses “the Venturi effect of a

converging/diverging nozzle to convert the pressure energy of a motive fluid to

velocity energy which creates a low pressure zone that draws in and entrains a

suction fluid.” Don’t ask me what that

means—it’s all engineering Greek to me, but trust me it was an important technological breakthrough and made

Giffard a very wealthy man.

In

fact, he became something of a national

hero for that and was made a Chevalier of the Légion d’ honneur

in 1866. And he was not done with

playing around with lighter-than-air-craft.

In 1876 he made a famous tethered

flight over Paris in a hydrogen balloon which was captured in a famous early photograph.

Despondent over declining health, Giffard committed suicide on April 14, 1882. He left his fortune to the people of France to be used for humanitarian and scientific causes. He was so esteemed by his countrymen that he is among the 72 great notables whose names are inscribed on the Eiffel Tower.

No comments:

Post a Comment