On October

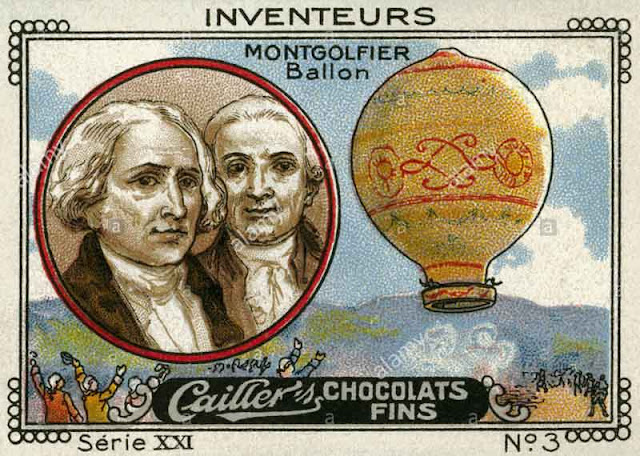

15, 1783 Jacques-Étienne Montgolfier became the first human being to leave the surface of the Earth and rise in the air in a man-made contraption. And what a contraption! The enormous hot air balloon that Étienne and his brother Joseph-Michel Montgolfier constructed was seventy-five feet tall

and about fifty feet in diameter with a 60,000 cubic foot capacity. It was elaborately

decorated in gold and deep blue with Fleur-de-lis, signs of the Zodiac, and suns emblazoned with the face of Louis XVI interlaced with the royal monogram. The balloon rose in the morning sky

over Paris on a tether from the workshop

where it had been created. A second flight the same day carried to

an even greater height—80 feet with passenger Pilâtre de Rozier, a chemist

and teacher who had become

interested in the experiments.

This

is generally cited as the beginning

of manned aviation. But there is one conflicting claim,

passionately supported in Portuguese speaking

lands. Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão a Brazilian born priest,

sketched elaborate drawings for an airship

lifted by hot air, certainly built models, and may have even left the ground in a prototype back in 1720. His fantastic creation was in the shape of a bird and even

included a propulsion system—sails which could be filled with bellows in the event of no wind. An account written in 1786, three years after

the Motgolfier flight claimed:

…in 1720, a

Brazilian Jesuit, named Bartholomew Gusmão, possessed of abilities,

imagination, and address, by permission of [King] John V. fabricated

a balloon in a place contiguous to the Royal

Palace, and one day, in presence of their Majesties, and an immense crowd

of spectators, raised himself, by means of a fire lighted in the machine, as

high as the cornice of the building; but through the negligence and want of

experience of those who held the cords, the machine took an oblique direction,

and, touching the cornice, burst and fell.…The balloon was in the form of a

bird with a tail and wings. The inventor proposed to make new experiments, but,

chagrined at the raillery of the common people, who called him wizard, and terrified by the Inquisition, he took the advice of his

friends, burned his manuscripts, disguised himself, and fled to Spain, where he soon after died in an

hospital.

Although

some of Gusmão’s drawing and papers have been found along with accounts of

displays with toys and models, most historians

discount a flight in a full scale craft.

This pisses the Portuguese off, who feel they have been snubbed. But then they don’t have the evidence of

thousands of Parisian eyewitnesses

and numerous artist renderings from

further flights.

The

brothers Montgolfier were younger members of the 19 children of paper maker Pierre Montgolfier of Annonay,

Ardèche. Joseph, the 12th child was born in 1740

and Étienne, the 15h, came five years later.

Joseph was brilliant but rebellious and sent away by the family

to study architecture in Paris.

When

the eldest brother and heir to their father unexpectedly died, Joseph was recalled from Paris, promoted

over older siblings, and put in charge of the family business. He made many innovations, including introducing the most modern techniques. His efforts gained the Royal notice and the company was commissioned to construct a

new mill and factory as a model

for the whole French paper industry—then

one of the most important in the country.

In

1777 Joseph idly observed laundry drying

over a fire. Sheets billowed and rose. Something was lifting

them. He concluded that it was an as yet

undiscovered gas released by combustion

which he modestly named Montgolfier Gas,

with a property he called levity.

It

was while contemplating a military

problem—the long siege of the impregnable British fortress of Gibraltar by French and Spanish forces—that he began to tinker with devises based on his

discovery. After months of bombardment and attacks by sea and land, the

Rock stood and along with it control of the gateway between the Mediterranean Sea and Atlantic Ocean. What if troops could be carried over

the fortress and landed with in it,

he wondered. Could his gas provide the

lift for such an undertaking?

He

began building models at Avignon in

November of 1782. His first construction

was a box-like chamber 3’ x 3’ x 4

out of a thin wood frame covered on the

sides and top with lightweight taffeta

cloth. He ignited some crumpled

paper under the box which quickly rose up in the air until it banged on the

ceiling. Joseph excitedly summoned his

younger brother from home to join him on his project, urging him to bring “a

supply of taffeta and cordage.”

The brothers built a new model three times as large which they tested outdoors in December. It floated for nearly 1.2 miles before landing and being destroyed by a frightened peasant.

The demonstration at Annonay in June 1783.The

brothers refined their invention for a formal first public display. Their new model was globular and constructed of sackcloth

lined with three layers of thin paper.

It had a capacity for 28,000

cubic feet of air and weighed about 500 pounds.

An invited audience, including dignitaries from the États

particuliers assembled at Annonay

on June 4, 1783 to witness flight of 1.2 mile reaching an altitude of 6,000

feet lasting 10 minutes. Officials

present naturally wrote enthusiastic reports to the government in Paris.

The

government equally naturally called them to Paris for further

demonstrations. Joseph, shy and clumsy

in society, sent Étienne to the capital to collaborate with wallpaper manufacturer Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, for a full

scale model of the device were

calling a globe aérostatique and he named Aérostat Réveillon. The first test of the glorious new

device flew from the grounds of la Folie Titon near Réveillon’s home.

Because

of concern that the upper air might

be dangerous to humans, the King graciously offered two the loan of two condemned felons as passengers for the

next public demonstration. Étienne

demurred and elected to send aloft a duck

as sort of a control animal known to withstand heights, a rooster thought not to be capable of flying at the expected

altitude, and a sheep about the same weight as a man. The animals were suspended below the

balloon in a basket.

A

crowd of thousands gathered to watch the flight, including the King himself and

Marie Antoinette on the ground of Versailles. The flight lasted approximately eight minutes,

covered two miles, and obtained an altitude of about 1,500 feet before landing

safely.

After

the manned ascent test in October, it was time for the great unveiling of for an untethered manned flight. On November 21 Pilâtre de Rozier was again in the

basket, accompanied by the Marquis

d’Arlandes, an army officer.

They took off from the Château de

la Muette near to the Bois de Boulogne

and were carried for miles above Paris at altitudes of up to 3,000 feet for 25

minutes. The craft landed outside the city

wall between two picturesque

windmills with enough fuel left to travel four times as far. But embers

from the fire set fire to the edge of the envelope which Pilâtre had to beat

out with his coat. Despite

the harrowing landing, the voyage was a success, the talk of Paris for days,

and commemorated in numerous etchings and on commemorative plates.

A cheap commemorative plate for he common folk got the year wrong. Much more elaborate plates were produced for the elite.

The

King raised the Montgolfier to the nobility. Several subsequent flights were also

made. But just as it looked like a rosy

future for all concerned, fate intervened in two ways.

First,

Jacques Charles and brothers Anne-Jean and Nicolas-Louis Robert, were

simultaneously experimenting with balloons using hydrogen for lift. They flew

an unmanned demonstration in August 1783 and on December 1 over a thousand

people paid to watch Charles and Nicolas-Louis Robert take off in La

Charlière, the first manned hydrogen balloon. That flight lasted over two hours and covered

over 22 miles.

The

French government concluded that hydrogen balloons were the future of viable

flight, and most subsequent energy

went into that. Hot air ballooning

remained a novelty, as it is to this

day.

The Montgolfier

returned to their paper business, which thrived and continues to this day. Étienne died in Switzerland in 1799 and Joseph at Balaruc-les-Bains in 1810.

Neither left children and the family business came into the hands of

other relatives.

Watching

the flight of the magnificent balloon festooned with his own image was one of

the last great triumphs of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. Fate—in the form of the Paris Mob—would not be kind to them.

Pilâtre

de Rozier became a dedicated balloon

enthusiast and constructed his own.

He piloted several flights. But

on June 19, 1785 he and a companion, Pierre

Romain were killed trying to cross the English

Channel in a hybrid hot air-hydrogen

balloon—not a good idea considering the volatility of hydrogen around a flame. They were the first

known casualties in aviation.

De

Rozier’s companion on the first untethered flight, the Marquis d’Arlandes, like the King and Queen, suffered the

catastrophic separation of his head from his body during the Revolution.

No comments:

Post a Comment