It has always chapped my ass to hear

people who don’t know what the hell they are talking about

wonder aloud about why “there was no resistance” when the Nazis

rounded up Jews and other “undesirables” or in the labor and

extermination camps. First, it is another example of blaming

the victim, that always popular parlor game. And

secondly it doesn’t take into account the information that

Jews had—early on even they could not imagine industrial scale murder

and genocide, a term that had not yet even been conceived—or

the overwhelming, highly organized force arrayed against them.

These comments come most prominently, but not exclusively, from right

wingers who want to promote an armed-to-the-teeth citizenry

to resist jack booted thugs and who think concentration camp escapes could

be played out like in The Great Escape and other movies.

In fact, many Jews who were able attempted to

escape. Others famously went into hiding, and some joined or

created resistance units. Individuals committed—and

were executed for, often along with family or community

members—attacks on Nazi police, troops, and local

collaborators. There were famously organized uprisings

in Warsaw and other ghettos.

But most Jews swept up in the machinery of

death were unprepared, confused, and needed to be protective of

family. Once in the camps those not immediately killed were worked

nearly to death, starved, frozen, and subject to

disease and within weeks were too physically weakened to

resist.

There were at least three attempts at mass

breakouts from the camps—at Treblinka on August 2, 1943 and at Auschwitz-Birkenau

on October 7, 1944 which included an uprising which resulted in one of

the crematoriums being blown up. In those two cases almost

all the attempted escapees were killed. But on October 14, 1943, about

600 prisoners tried to escape from the Sobibór camp in eastern Poland.

About half got beyond the wire and about 50 survived to

the end of the war. This is their story.

Sobibór was a village in a sparsely populated

region of eastern Poland. The Nazis had established 18 labor camps in

the region. The new camp near the village was constructed in the spring

of 1942 to receive Jews from Poland, France, Germany, the Netherlands,

Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, and Soviet POWs and to screen

them for assignment to the labor camps—and to quickly dispose

of those deemed unsuitable or unusable. Fewer than 1,000 inmates

were held there at any time. Many of those selected for the labor camps

were there for only hours or days. The life expectancy of the rejects

was days or short weeks.

The camp was mostly built by local villagers

and a Sonderkommando, a group of about eighty Jews from ghettos in the vicinity

of the camp guarded by a squad of Ukrainians trained at Trawniki.

Upon completion of construction, these Jews were shot. The gas

chambers at the new camp were hooked up to large internal

combustion engines which pumped in carbon monoxide rich exhaust to

smother the victims. Similar technology had been

used on a smaller scale with closed busses, but this was the

first major application on a large scale. The chambers were tested

in April on twenty-five Jews from Krychów who were satisfactorily

asphyxiated. After that the camp went into full operation and

the nearby rail platform became a busy place.

To give an idea of how efficient the operation was,

it was active from May 1942 to October 1943 when it was closed and replaced

by larger and more modern camps. But in less than 18 months

at least 200,000 and perhaps as many as 250,000 men, women, and children were murdered

there, the vast majority of them Jews.

Jews from Poland and the USSR knew what was going

to happen to them. They arrived in packed freight cars often hysterical

with fear and grief. Many were shot on the platform when

they did not respond quickly to orders. On the other hand, at

least in the early going Jews from Western Europe arrived in overcrowded

passenger coaches. They had been assured that they were going

to labor camps and were allowed to bring some luggage.

Their own doctors and nurses were allowed to attend the ill

in transit. Food and water during the journey were at least

adequate. These folks received the shock of a lifetime

arriving on the same platform. Because many were in better health than

Eastern Jews, able bodied men and women were often separated immediately

from their families and sent to the work camps even before they entered

Sobibór.

Attractive young women and girls were

often singled out and sent to the secluded forester house run

as a brothel for the camp’s SS contingent. Post war

trials highlighted the experience of two Austrian actresses, Ruth

and Gisela who were gang raped there over a period of days before

being taken outside and shot. Others befell the same fate.

Some prisoners were held at the camp for longer periods

as laborers including attending the gas chambers and crematoria.

Some were assigned, under heavy guard, to wood cutting beyond

the camp wire for fuel for the crematoria pyres.

From time to time, one would melt away into the forest and make

an escape. Some of those who did managed to find and

join resistance units operating from the nearby wilderness.

In the spring and summer of 1943 rumors began to

circulate in the camp that it was to be shut down. This was based

on a reduction in the numbers of incoming prisoners. In actuality,

this was due to new camps being opened. At this point SS officials

actually had plans to expand Sobibór. Fear of what might

happen to them seemed confirmed when survivors of the Bełżec

camp, one of the first extermination camps on Polish soil, was closed, arrived

at the Sobibór rail station only to be immediately shot in mass.

Polish Jews on some of the labor gangs began to organize

an escape committee by late summer. They knew that they would have

to act quickly before it inevitably became their turn in

the gas chambers. In September several Jewish Red Army prisoners

from Minsk arrived. Although there was initial distrust

between the Poles and the Soviets, several of the POWs joined the

plot and provided some military experience and leadership.

The plan was brutal in its simplicity.

On signal, prisoners would overpower and kill all of the SS men and

Ukrainian guards in the camp, using hidden homemade weapons and then

taking the arms of the Nazis. They would go from barracks to

barracks liberating the inmates and march out the front gates.

The Soviets and those who wished to join them would head east to

try to link up with Russian troops. Others would scatter

and make their way as best they could.

On October 14, 1943 under the leadership of

Polish prisoner Leon Feldhendler and Soviet POW Alexander Pechersky

they quickly managed to quietly overcome and kill 11 SS men and unknown number

of guards. But they were discovered,

and the alarm went out. Under intense fire inmates ran for their

lives scrambling over, under and through the fences as they were able. About 300 out of the 600 prisoners in the

camp made it out, but they had lost cohesion.

158 inmates were killed by the guards during the

escape attempt or died in the minefield surrounding the camp. 107 others were captured over the next few

days as SS troops, guards, and police swept the woods. All were immediately executed. Of the remaining survivors 53 died of other

causes before the end of the war—many of starvation, freezing to death, or

illness as they hid out in the forests.

About 50 eluded capture, made it to Soviet lines, and survived the war.

After the uprising a furious Heinrich Himmler

ordered the remaining prisoners killed, the camp closed, dismantled, and

the ground planted with trees. The gas chambers and

crematoria were destroyed, buried, and covered over with

an asphalt roadway. They were rediscovered in archeological

excavations in 2012.

The site of the camp is now Polish historic

site. Monuments on the grounds and at the railway station and

a small museum commemorate the dead and the uprising. The Dutch,

who lost more than 36,000 citizens at Sobibór famously including Helena

‘Lea’ Nordheim the Jewish Gold

Medal women’s gymnasts from the 1928 Olympics and the

team’s coach, Gerrit Kleerekoper have contributed funds to the upkeep and maintenance

of the site as well as newly installed signage.

After the war SS commandants, officers, and guards

were tried for war crimes. One of the most celebrated

cases took years. John Demjanjuk had been a Ukrainian POW when

he was recruited along with many others as a camp guard. He was

trained at the Trawniki concentration camp. He served as a tower

guard at Sobibór. And would have been among those who opened fire at

the fleeing escapees. After the war Demjanjuk made his way to the United

States as a displaced person. He became an American

citizen, married, and raised a family, settled in a suburb of

Cleveland where he worked as a mechanic at a Ford plant.

In 1975 Demjanjuk was finally identified as a

Ukrainian collaborator and his Nazi ID from Trawniki turned over

the Justice Department, which began deportation proceedings

against him two years later. He fought his deportation for years,

claiming at first that he was misidentified, and later that he was a

guard but had taken no part in executions or shootings. Israel

issued an extradition request for him in 1983 and he was deported to trial

there in 1986. Despite controversy over the authenticity of

the SS identification card and other issues, on April 18, 1988 Demjanjuk was convicted

in the Israeli court of being the notorious guard known to prisoners as Ivan

the Terrible. He was sentenced to death.

After serving more than 5 years in solitary confinement during appeals,

the Israeli Supreme Court overturned the conviction on the grounds of new evidence that identified

the real Ivan the Terrible as another Ukrainian, Ivan Marchenko.

Demjanjuk was released to return to the United

States. In 1993, the Sixth Circuit Court

of Appeals ruled that he was a victim

of fraud on the court, as lawyers with the Office of

Special Investigations had recklessly

failed to disclose evidence. In a report submitted to the Sixth Circuit

prior to the Israeli acquittal, Federal

Judge Thomas A. Wiseman, Jr. concluded that Federal officials

had erred in asserting that

Demjanjuk was Ivan the Terrible, but that evidence instead pointed to Demjanjuk

playing a lesser role as an SS guard.

After the Court of Appeals remanded the matter to Judge Wiseman, Judge

Wiseman dismissed a

denaturalization petition in 1998, effectively restoring Demjanjuk’s citizenship.

In 1999 the government filed a new civil complaint against Demjanjuk

asking again for denaturalization on the grounds that he was a guard at the

Sobibór and Majdanek camps in Poland under German occupation and at the Flossenburg camp in Germany. It also

accused Demjanjuk of being a member of an SS-run

unit that took part in capturing nearly two million Jews in the General Government of Poland. In a new trial in 2002 he was again stripped

of citizenship. He lost an appeal in

2004 and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case.

In December 2005 an immigration judge ordered Demjanjuk’s deportation to Germany,

Poland, or the Ukraine. He sought

protection under the United Nations

Convention Against Torture, claiming that he would be prosecuted and tortured if he were deported to

Ukraine. Chief U.S. Immigration Judge

Michael Creppy ruled there was no

evidence to substantiate Demjanjuk’s claim.

Demjanjuk lost

more appeals in his lengthy battles, finally exhausting them all. Then Germany served extradition papers seeking custody of him. Finally, after another round of appeals

seeking relief from the extradition, Demjanjuk was finally deported on May 11, 2009.

On July 13 prosecutors charged him with 27,900

counts of accessory to murder. The aging

and ill man could only briefly attend court sessions each day

and his lawyers asserted that due to

the complexity of the case it

would take up to five years to try the case.

They ask that the case be dismissed

due to his age, infirmity, and unlikelihood that he would survive

the trial. Then the Ukrainian government interceded on his

behalf arguing for mercy. None the less,

the trial got underway in November.

On May 12, 2011, Demjanjuk, then 91, was convicted

and sentenced to five years in prison. He was released pending

appeal and died in a German nursing home on March 17,

2012. The German high court then invalidated the conviction since

the appeal could not be heard.

Justice ground slowly for the accused guard.

It ground not at all for the dead of Sobibór.

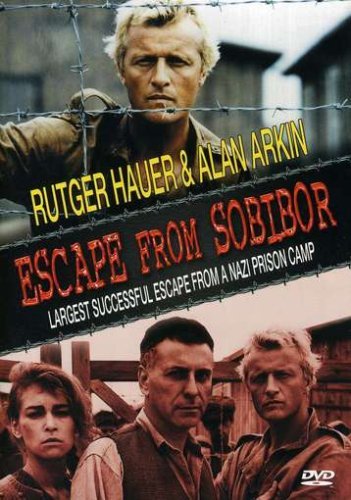

In 1987 Escape from Sobibor was filmed as

a British made-for-TV movie starring Rutger Hauer and Alan

Arkin which was also shown on CBS TV in the United States.

Hauer won a Golden Globe for his portrayal of Soviet POW leader

Lieutenant Aleksandr Pechersky.

No comments:

Post a Comment