Fouier-Major Augustin de La Balme of the Gendarmerie de France, a personal Guard Regiment of the King, was decorated and respected cavalry officer despite his low birth.

Col.

Augustin de La Balme was a French cavalry officer who came to the American shores as an early volunteer with the Continental

Army in 1777. The veteran officer had dreams of glory and advancement that were not realized. Three years later he died in a desperate fight

after being ambushed and besieged in a makeshift mud fort on the banks of an obscure creek in what is now Indiana. How he got there and just what the hell he

thought he was going to accomplish are matters of some considerable mystery and dispute.

He was born as Augustin Mottin on August 28, 1733 in the shadows of the French Alps in the Saint-Antoine-l’Abbaye, which was also known as La-Motte-Saint-Didier. His father was not a noble, but a tradesman—a

tanner. His family was well enough off, however, to buy

his admission as a trooper into the

prestigious Scottish Company of the Gendarmerie de France,

a personal regiment of the King and one of two Guards regiments. Mottin was evidently a brave and competent soldier and despite his lowly birth rose to become an officer

during the Seven Years War. He was one of the few cavalry officers to survive the disastrous Battle of Minden in 1759.

Mottin subsequently became the Riding Master at the Gendarmerie Riding School in Lunéville. He retired

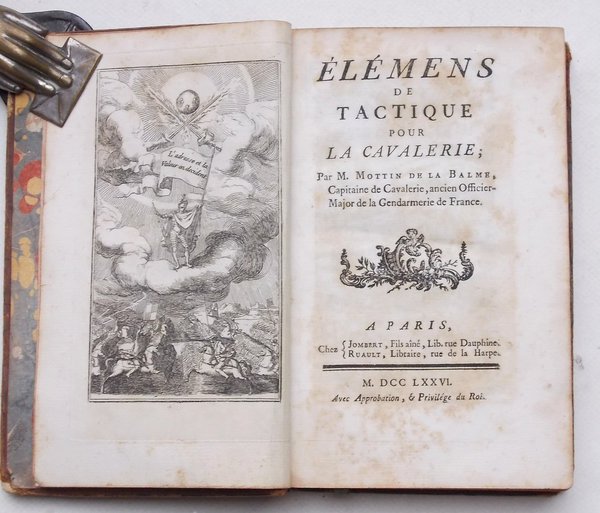

on pension with the rank of Fourrier-Major in 1773 and wrote two

highly regarded manuals, one on horsemanship and the other on cavalry tactics under the nom

de plume Augustin de La Balme.

The books made him well known in European

military circles.

La Balme's tactical cavalry manual made him well known in European military circles. He came to the Continental Army a far more experienced officer than the young Marquis de Lafayette but failed to catch Washington's eye or affection.

In 1777 La Balme, as he was now

known, became one of a small handful of

French officers who without

permission—but perhaps with a wink

and a nod—came to the rebellious colonies

the best known of whom the younger, dashing, and noble-born Gilbert du

Motier was, Marquis de Lafayette. Lafayette was rewarded with a commission as a Major General and quickly became an aide and favorite to Commanding General George Washington of the Continental

Army.

The far more experienced La Balme

was made a Colonel and appointed the Army’s Inspector of Cavalry, a post much more impressive in title

than in reality. The American’s

had never really developed a cavalry tradition.

Outside of a few locally raised companies,

widely scattered, and armed and trained to different drills and uses,

there was no major Continental cavalry force.

La Balme hoped to create order out of chaos, consolidate training based on his own methods and eventually be placed

in direct command of a regiment of mounted regulars.

Washington concluded that the

creation of a regularized cavalry was needed, especially for operations in the South where mounted Tory

units under Banastre Tarleton

were proving devastatingly effective. But the Polish

officer Casmir Pulaski caught

Washington’s ear and was commissioned to form the cavalry unit that came to be

known a Pulaski’s

Legion. The Pole, not La Balme,

became known as the Father of the American Cavalry and went on to glory and death leading

an ill-conceived charge on English guns trying to re-take Savannah.

The French settlement of Kaskaskia on the Mississippi River in the Illinois country in the late 1700s. The Jesuit compound in the foreground was latter transformed into a Fort with guard towers at the corners of a raised palisade. It was that fort that George Roger Clark took for Virginia and where La Balme materialized with his scheme to take far distant Fort Detroit.

Disgusted at the snub, La Balme resigned

his Continental Army commission in 1780.

He next appeared in the frontier

town of Kaskaskia on the Mississippi River in the Illinois country. What he was doing there and under whose,

if any, orders, is a bit of a mystery. He showed up in the uniform and identity of

a French officer, not a Continental

one. He brought with him a French Fleur

de Lis flag, not a Continental

banner.

Apparently, he had a plan inspired

by George Rogers Clark’s

daring success in liberating the

River settlements from the English

and then marching overland to take Fort Vincennes. La Balme planned to raise a force from among the French militia in the scattered

settlements and make an even longer overland trek to seize the English western stronghold at far away Fort Detroit. He expected the large French population

in the region, including those in the fort, to join him.

Some say that he was operating under secret orders from Washington, but no evidence of this has ever been

found. Others think Washington gave tacit approval to the scheme. Still others believe that La Balme was acting

purely on his own and wonder if he

planned to capture the fort

for the Americans, the French, or perhaps to establish an independent

French speaking country from what had been Lower Quebec. Claiming

it for France seemed to make little sense because the English were in firm control of Quebec and Upper and Lower Canada to the east and unlikely to lose that grip. And he could not connect to the south with Louisiana which was then in Spanish hands.

The sudden appearance of a French

officer among them cheered the

settlers of the Illinois Bottom. They had chaffed at English rule and the disruption of their old fur

trading patterns with the native

tribes. But they were also distrustful of their new masters, the Virginians. La Balme collected

the complaints and concerns of the local citizens and sent them by messenger to the French agent at Fort Pitt,

presumably to be acted on by the Governor

of Virginia, then Thomas Jefferson.

La Balme gathered his forces and

began to execute his plan by ordering a diversionary

attack on Fort St. Joseph at the

mouth of the St. Joseph River on the

shores of Lake Michigan. That small

force was consisted of settlers from Cahokia

led by militiaman Jean-Baptiste Hamelin and Lt. Thomas Brady, one of the few

Virginia officers on the frontier. After

raiding and looting the supply depot for English allies the Miami and Potawatomi, the party was hunted

down and defeated by a native force led by British Lt. Dagreaux Du Quindre at Petit Fort in the Dunes at the lower end of the

Lake. Instead of a diversion,

the action alerted the English and their allies that military activity was picking up on the frontier.

The French officer was unaware and unprepared for the realities

of campaigning on the frontier, including the grueling long marches over swampy ground, through thick forests,

and across prairies where the tall grass waved high above men’s heads

making navigation difficult. There were only rudimentary Indian and deer trails, and sometimes none at

all. There were several streams and some good sized rivers to ford, luckily at low water,

in the fall.

He had also picked a time of year

when the enemy tribes had hunting parties out preparing for the winter making an accidental encounter that would tip his hand more

likely. Fortunately, his militiamen

included not just bottom land farmers, but experienced

voyagers and fur traders who knew the country.

La Balme left the country around

Kaskaskia and Chahokia with about 60 men and expected to rally more at

Vincennes. After re-tracing Rogers’s

march, he arrived at Vincennes and indeed found eager recruits. From there he followed the Wabash and collected more men at the settlements of Ouiatenon (present day West Lafayette, Indiana) and Kekionga (now Fort Wayne).

At Keionga he expected to capture the British agent Charles

Beaubien, and a number of Miami known to be there—and perhaps even hoped to

turn them into allies. But the agent and most of the tribesmen were gone for the long hunt. La Balme raised

the French flag and paused three days to recruit locals and to loot the supplies of the trading post. He sent out scouts to raise more volunteers, but

none arrived.

La Balme now had around one hundred

men under his command and was still far from Detroit. He decided to split his forces, leaving about twenty of his

men to garrison Keionga while he marched

on a quick side-raid on a trading

post on the Eel River. But the returning Miami hunting party had

spotted the French flag over Kekionga.

The large hunting party easily overwhelmed

the small garrison.

Unaware that he had lost his base and his rear was exposed, La Balme pressed on. Little

Turtle, a local Miami chief

from a village on the Eel River was alerted by runners from Kekionga who had easily gotten ahead of La Balme’s slow

moving party. Little Turtle gathered his

warriors and laid an ambush at a key ford of

the river. La Balme marched right into

the trap.

There was a sharp fight and both sides were, at first, evenly matched. The

surprised militiamen rallied and

were able to dig mud fortifications

along the riverbank. The battle settled into a siege with La Balme hoping for aid from Kekionga or from other

French settlements. Meanwhile more Miami

gathered and his forces were picked off

one by one.

Accounts differ as to how long the

French held out. Some say days,

some say a week or more.

It was unlikely at the longer range of the accounts. On or about November 3, 4 or 5 La Balme was

killed. Finally, his men were overwhelmed

and most of them killed. Only a handful would live to return to their

homes.

The mission was a failure and La

Balme, far from winning glory, became all but forgotten. This minor side show to the American

Revolution had no strategic importance. But it did accomplish one thing. The English were so alarmed by the activity on the frontier that they decided they had

to garrison Fort Detroit and a string of

frontier forts with British Regulars and Major de Peyster subsequently deployed

a detachment of British Rangers to

protect Kekionga. This diverted experienced troops from action

on the frontier closer to the Allegany

Mountains and American settlements.

The biggest beneficiary was Little Turtle whose prestige as a Miami war

leader was enhanced. By the end of the decade, he would become the

main war chief of the tribe and a key leader of the Western Indian Confederacy in its war with the United States. He

smashed an American army lead by General

Josiah Harmar in 1790 and another led by General Arthur St. Clair a year later.

The Confederacy, then under the

command of Blue Jacket, was finally defeated by General Mad Anthony Wayne at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 after

the wily Miami chief urged caution

and making peace with the “soldier who does not sleep.”

La Balme may have fallen out of

American history books, but he is remembered, a bit, in Indiana. In 1930 the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) erected a small monument—a plaque on a boulder at

the site of La Balme’s

Defeat. The Indiana Society of the Sons of the American Revolution commemorated

the 225th anniversary of the battle in 2005 with decedents of both the French militia men and the Miami warriors

present, a re-enactment and unveiling of a new, large state historical marker.

Nice, but not quite the glory the old cavalryman had in mind.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment