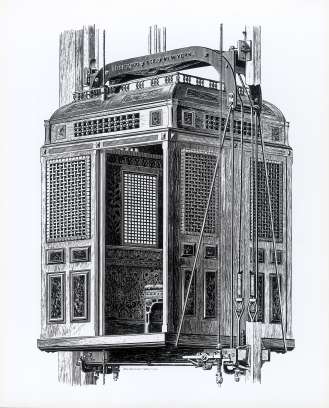

On March 23, 1857 Elijah Graves Otis, a former itinerant Yankee jack-of-all-trades and tinkerer turned entrepreneur

installed his first successful commercial passenger elevator in a four story building at 488 Broadway in New York City. After that,

you should pardon the expression, Otis’s fortunes

were on the way up as sales for

his invention took off. The lift made large scale multi-story industrial

and commercial buildings practical. In a few more decades it would be critical to the development of the skyscraper.

Otis’s invention was not so much the

lift itself—various kinds had been in limited

use for decades, mostly operating like over-sized

dumb waiters on a block and tackle hoist. But these lifts

were limited by the weight they could handle and wear

and tear on the ropes meant that

they often crashed when the cord snapped. His breakthrough was an effective locking mechanism on a traction lift that prevented the platform or

car from falling. His safety

elevator soon made all other lift systems obsolete.

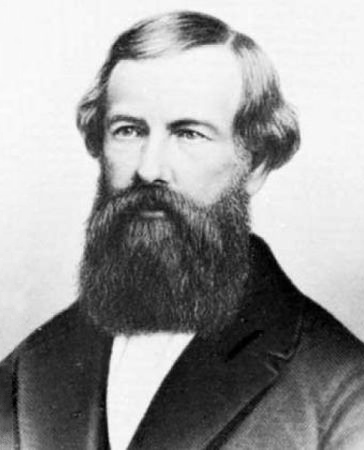

Otis was born on August 3, 1811 in

the small town of Halifax, Vermont just over the border

from western Massachusetts, even at

that late date a fairly rustic

almost frontier community. His father

was a farmer but as a boy he was drawn to the

village blacksmith shop where he was

fascinated with tools, making things, and tinkering. He

may have served a kind of informal

apprenticeship to the local smith who appreciated

the hero worshiping attention.

Restless

and determined to escape the fate of a

stone field farmer he left

home at age 19 determined to find something better. Thus began his wandering years marked by a series

of jobs and business ventures each requiring the mastery of some new set of skills.

He eventually settled in Troy,

New York where he worked as a teamster,

carefully saved his money, and kept

an eye out for opportunities. He married Susan A. Houghton in 1834 but later the same year contracted

a nearly fatal case of pneumonia. He recovered and the couple had a son, Charles. By 1838 Otis had

saved enough money to buy property on

the Green River in the Vermont hills. He designed

and built by his own hands a gristmill on the river. When that failed to prosper he converted it

to a sawmill. When that didn’t work out, he turned to building wagons, for which he turned

out to be highly skilled. Just as he seemed well established with a

prosperous future, Susan died shortly after giving birth to a second son Norbert.

Eight year old Charles was already

working alongside his father, but Otis needed a mother for his second son who

was still in diapers. Finding no local

prospects, he sold his business and moved to Albany, New York where he found a second wife and a job as a doll maker. Once again he quickly mastered his new

craft but was dissatisfied that in a 12 hour shift he could make only a

dozen dolls. Since he was on piece work he began tinkering with ways

to mechanize at least part of the

production. He invented a robot tuner—a lathe that could turn out multiple items following a master pattern. Although useful in turning out rough

parts of doll bodies, both Otis and his employer recognized it was much more

valuable for turning spindles used

in the production of bedsteads. From the production of no more than 50 pieces

a day on a single lathe, his new process

could make 200. His delighted boss bought his patent for $500, a respectable

small fortune.

With that cash and his savings Otis

boldly opened his own business. He

invented and tried to market a safety

brake that could stop trains

instantly and an automatic bread

baking oven. Just as the business

was beginning to get established the city of Albany diverted the stream he was using to power his mill for its fresh

water supply. He

was ruined when he was left with no

way to run his machinery.

Embittered

he left Albany for good in 1851 and relocated with his family to Bergen City, New Jersey where he worked as a mechanic, then to Yonkers, New York.

He found an ideal opportunity in Yonkers when he was hired to convert a

deserted sawmill into a bedstead factory of which he would become the general manager. But first there was the problem of gutting the multi-story mill including removing its heavy machinery and tons of debris,

which he decided to move to the top

floor which he did not plan to use.

Working with his now teenage sons, he devised his safety elevator

because the rope-and-pulley hoisting platforms used for such work often failed

dramatically. The system worked perfectly

and Otis was able to get his new factory up and running.

But he considered it little more

than tinkering on the fly to solve an immediate problem. Otis did not immediately bother to patent his

invention or pursue marketing it. But

when sales at the bedstead factory began to decline, Otis decided to turn back

to that safety elevator design. In 1853

in partnership with his sons he founded the Union Elevator Works which quickly became the Otis Brothers Inc.

Now all he had to do was convince potential customers to buy his

innovation. It is always hard to sell people what they don’t know they need. Otis was frustrated with his initial efforts

but in 1853 a grand opportunity presented itself—the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, Americas first stab at

what became known as a World’s

Fair which was held that year in New York City’s Bryant Park in a Crystal

Palace inspired by the London

structure of the same name built in 1851 for the original Great International Exposition.

The New York exhibition may have

been a pale copy of its British inspiration but it dazzled

Americans with displays of the latest industrial

and technological innovation. Walt Whitman in his poem The Song of the Exposition enthused:

... a Palace,

Lofter, fairer, ampler than any yet,

Earth’s modern wonder, History’s Seven out stripping,

High rising tier on tier, with glass and iron facades,

Gladdening the sun and sky-enhued in the cheerfulest hues,

Bronze, lilac, robin’s-egg, marine and crimson

Over whose golden roof shall flaunt, beneath thy banner, Freedom.

Newly inaugurated President Franklin Pierce still reeling from the death of his son in a freak railroad accident on the way to Washington to assume office, managed to

bestir himself from the alcoholic stupor he kept himself to

come up to New York to bless the

opening of the Exposition with Presidential

dignity in July of 1853. A then

astonishing 1.1 million visitors attended the fair in the 18 months it was

open.

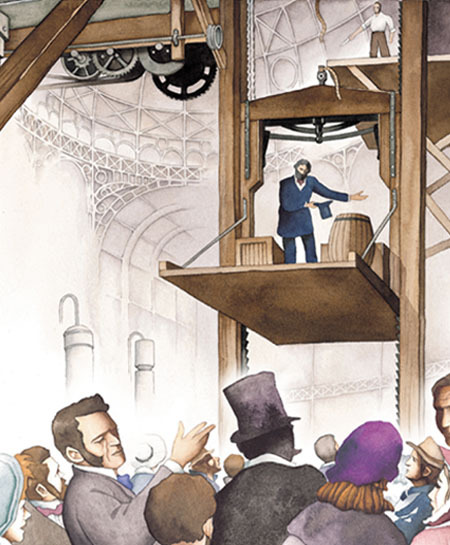

With an audience like that and breathless

accounts of the exhibits and doings filling newspaper columns across the nation, Otis got in on the

action. He and his sons constructed a

working three story high open platform

lift in the Crystal Palace. To inaugurate his exhibit before record breaking crowds, he enlisted the

aid of the nation’s leading promoter and

entertainment impresario—Phineas T. Barnum himself.

One afternoon at the Fair in 1854

Otis stood on the open platform of his contraption

along with several barrels and crates weighing several hundred

pounds. He demonstrated that the

platform would lift him and the freight and

that it could lower it again. That in

itself did not astonish the audience—they had seen or heard of other lift

devices. But then he brought out Barnum

who with much fanfare swung a broadsword severing the hoist rope with the platform still high

above the heads of the crowd which gasped in horror. The

platform dropped, but only a few

inches—its fall was jarringly but effectively arrested by Otis’s safety

break gizmo. The crowd went wild. The demonstration was repeated

daily—minus Barnum—always with the same satisfying results.

Orders for his commercial lifts

began pouring in sales doubled every two years.

But it took three years to persuade a developer to install one for passenger

use in a commercial building. The success of his Broadway installation in

1857 finally led to that market opening up as well.

Otis continued to tinker on

improvements, including a three-way

steam valve engine, which could transition

the elevator between up to down smoothly and stop it rapidly. He wrapped up

several other clever improvements in a new 1861 patent, which became the basis

for all modern elevators. Meanwhile the

restless inventor returned to his old projects and patented versions of his engineer-controlled railway breaking system—state of the art until George Westinghouse’s

air breaks decades later and his industrial scale bread baking ovens.

Then at the age of only 49 and a

seemingly limitless future ahead of him, Otis contracted diphtheria and died on April 8, 1861 just as the nation was headed

into Civil War.

His company came into the capable hands of his sons. Charles, who had tinkered alongside his

father for years, became a respected

engineer who continued to develop new patents for the company and supervise

sometimes complex installation projects.

Younger son Norbert turned out to be a gifted executive who shrewdly

guided the growth of the company.

Although the turmoil of the Civil

War somewhat impeded the growth of the company, it took off in the post-war industrial boom and especially

with the explosive growth of cities whose crowded central cores demand taller

and taller buildings. The introduction of steel girder frame construction was the breakthrough that led to true modern skyscrapers. The

Otis Elevator company kept up with innovations that made reaching for the stars possible.

The company also developed the escalator.

Otis Elevator remained in private

hands for many years but is now a division

of the conglomerate UTC Climate, Controls & Security. The Otis brand, however, remains the gold standard in

elevator construction, installation, and maintenance.

No comments:

Post a Comment