Although it barely made a ripple in the American press and media in 2021 something astonishing happened while we were focused on an insurrection, an inauguration, and the Coronavirus pandemic. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), a/k/a the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty came into effect on January 22 making the ultimate weapons of mass destruction internationally illegal. Of course not a single bomb was disarmed and no defiant malefactor states held accountable. Yet however simply symbolic, the Treaty represented a major breakthrough and offered some dim hope that the famous Doomsday Clock might be turned back just a bit.

The Treaty came into effect after Belize, Jamaica, Malta, Nauru, Nigeria, Niue, Sudan, and Zimbabwe either signed or acceded to the agreement in 2020 bringing the total number of supporting states to 86 signatories and 51 parties.

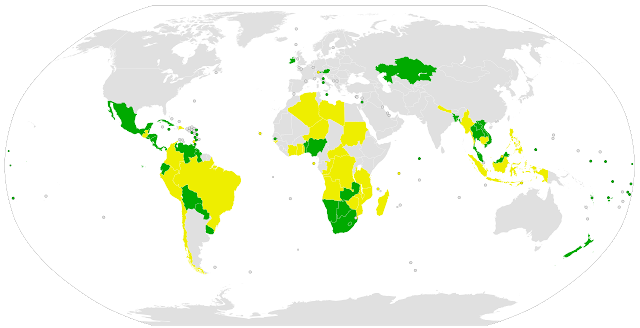

This map shows the parties to the Treaty in green and the signatories in yellow as of the agreement becoming international law.Who didn’t sign? Every acknowledged or suspected nuclear power—the United States, Russia, United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea—or states on the verge of developing weapons like Iran. Most reasonably advanced industrial nations with access to plutonium or enriched uranium can probably join the nuclear club within a few years of intentional development. Of these with at least rumored aspirations only Brazil signed.

Only a handful of small Western European nations—Ireland, Austria, Liechtenstein, San Marino, the Vatican, and Malta are in the pact. No members of NATO are. In Eastern Europe Kazakhstan is the lonely member of the anti-nuclear agreement.

So who do we thank for this international breakthrough? Almost all of Latin America and the Caribbean, much of Africa, Southeast Asia, and Oceania. Many of the signatories were among the smallest nations on Earth in both population and land mass punching way above their weight.

Some may wonder why if the treaty doesn’t include those with the ability to blow up the world and is apparently toothless for enforcement it matters at all. Its proponents assert that is an “unambiguous political commitment” to achieve and maintain a nuclear-weapon-free world. Unlike a comprehensive nuclear weapons convention, it was not intended to contain all of the legal and technical measures required to reach the point of elimination. Such provisions would instead be the subject of future negotiations.

The Ban Treaty helped stigmatize nuclear weapons and serve as a catalyst for a move to elimination. Unlike other weapons of mass destruction—chemical and biological—or recklessly indiscriminate to civilian populations—anti-personnel landmines and cluster munitions—nuclear arms are not prohibited in a comprehensive and universal manner. The Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) of 1968—the oldest and most important curb on such arms, contains only partial prohibitions, and nuclear-weapon-free zone treaties prohibit nuclear weapons only within certain geographical regions.

Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp was a series of protest camps established to protest nuclear weapons being placed at the Royal Air Force (RAF) base in Berkshire, England in 1981, a catalyst event for the international anti-nuke movement.

The origins of the treaty can be traced directly back to the Ban the Bomb movement of the 1950’s, the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp in Britain in 1981, and 60 years of peace activism as expatriate American singer and activist Peggy Seeger, a long-time resident of the United Kingdom, pointed out.

That anti-nuclear activism has waxed and waned over the decades and has often been overshadowed by anti-war activism on specific conflicts from Vietnam to Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and perpetually Israeli/Palestinian. But it never went away.

Proposals for a nuclear weapon ban treaty first emerged following a review conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in 2010, at which the five officially recognized nuclear-armed state parties—the U.S. Russia, Britain, France and China—rejected calls for the start of negotiations on a comprehensive nuclear weapons convention. Disarmament advocates first considered starting this process without the big five states as a path forward and a less technical treaty concentrated on the ban of nuclear weapons appeared to be a more realistic goal.

Three major intergovernmental conferences in 2013 and 2014 on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons, held in Norway, Mexico, and Austria, strengthened the international resolve to outlaw nuclear weapons. The second such conference, in Mexico in February 2014, concluded that the prohibition of a certain type of weapon typically precedes, and stimulates, its elimination.

In 2014, a group of non-nuclear-armed nations known as the New Agenda Coalition (NAC) presented the idea of a nuclear-weapon-ban treaty to the NPT state parties as a possible “effective measure” to implement Article VI of the NPT, which required all states parties to pursue negotiations in good faith for nuclear disarmament. The NAC argued that a ban treaty would operate alongside and in support of the NPT.

In 2015, the UN General Assembly established a working group with a mandate to address “concrete effective legal measures, legal provisions and norms” for attaining and maintaining a nuclear-weapon-free world. In August 2016, it adopted a report recommending negotiations in 2017 on a “legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading towards their total elimination”. The vote on the resolution was 123 in favor, 38 against, and 16 abstaining. North Korea was the only country possessing nuclear weapons that voted for this resolution, though it did not subsequently take part in negotiations.

Ambassador. Elayne Whyte Gómez, Permanent Representative of Costa Rica to the United Nations Office in Geneva was President of the UN Conference sessions that drafted and adopted the Nuclear ban treaty.

The United Nations Conference to Negotiate a Legally Binding Instrument to Prohibit Nuclear Weapons, Leading Towards their Total Elimination first met in March 2017 at U.N. Headquarters in New York City. 132 nations participated. At the end, the President of the negotiating conference, Elayne Whyte Gómez, permanent representative of Costa Rica to the UN in Geneva, called the adoption of a treaty by July 7 “an achievable goal”. Representatives from governments, international organizations, and civil society, such as the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, noted the positive atmosphere and strong convergence of ideas among negotiating participants. They agreed that the week-long debates set the stage well for the negotiations in June and July.

After Gómez presented a first draft of the treaty in May several European and NATO nations noted that draft Article 1, 2a prohibiting any stationing of nuclear weapons on their own territory would require them to end contracts on nuclear sharing with the US. They therefore refused to participate in on-going negotiations. The only NATO member participating in the treaty negotiations was the Netherlands which came under enormous diplomatic pressure from America and Germany.

The second conference started on June 15 and was scheduled to conclude on July 7, with 127 out of 193 UN members participating. On June 27 “Join and destroy” language was added for current nuclear powers which was somewhat modified later. A new provision added acceptance of the peaceful use of nuclear technology.

A final third draft clarified language but also debated a limited escape card. The withdrawal clause provided “in exercising its national sovereignty, [...] decides that extraordinary events related to the subject matter of the Treaty have jeopardized the supreme interests of its country”. The majority perspective was that this condition was subjective, and no security interests can justify genocide, nor can mass destruction contribute to security. Since a neutral withdrawal clause not giving reasons was not accepted by the minority, the respective Article 17 was accepted as a compromise. Safeguards against arbitrary use are the withdrawal period of twelve months and the prohibition of withdrawal during an armed conflict.

The much tinkered with final draft was adopted on July 7 was with 122 countries in favor, 1 opposed (Netherlands), and 1 abstention (Singapore). Among the countries voting for the treaty’s adoption were South Africa and Kazakhstan, both of which formerly possessed nuclear weapons and gave them up voluntarily. Iran and Saudi Arabia also voted in favor of the agreement although Iran seemed to be in development of the weapons and the Saudis had financed Pakistan’s Islamic Bomb and was suspected of planning to buy the results for its own use.

Global Parliamentarians, many of them from Western nations but not in governments, campaigned for the Treaty's adoption.Not every nation that voted for adoption ultimately officially signed the treaty or became parties to it. 57 nations signed in 2017. Others followed in fits and starts over the last four years until the critical mass to make the treaty official international law.

In December 2021, Joe Biden’s Secretary of State Antony Blinken, said:

We do not support the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Seeking to ban nuclear weapons through a treaty that does not include any of the countries that actually possess nuclear weapons is not likely to produce any results.Along with other nuclear-armed states, the United States said that it does “not accept any claim that [the TPNW] contributes to the development of customary international law”. It also called on all states that are considering supporting the TPNW “to reflect seriously on its implications for international peace and security.”

n October 2020 with the TPNW’s entry into force imminent the US called on states that had already ratified the treaty to withdraw their support. However, in September 2021, the Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and international Security Bonnie Jenkins, said that the United States is no longer “telling countries that they shouldn’t sign” the TPNW.

The incoming Biden administration was expected to resume negotiations with Iran over the agreement that Trump abandoned in which they agreed to halt arms development. It leaned on Israel on their implied threats to use the nukes that they pretend not to have against regional rivals.

Relations with North Korea were entirely unpredictable. The administration remained committed to the traditional American position of nuclear deterrence, although it left the door slightly ajar to negotiations to stave off an expensive new arms race and perhaps somewhat reduce the Pentagon nuclear arms budget.

In Russia Vladimir Putin has been belligerent on nuclear weapons believing that they are essential to rebuilding Russian prestige and influence as a world power. He has long promoted the use of tactical nuclear weapons which could be deployed if NATO pressed too closely in the old Soviet sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. After his full scale invasion of Ukraine bogged down with heavy casualties and enough heavy armament and artillery destroyed to seriously drain Russian arsenals and Western boycotts and sanctions devastated the economy Putin publicly advanced the notion he was ready to use nukes on the battle field, against infrastructure, and even against staging areas for Western arms supplies in adjacent NATO states. Trump’s cozy subservient relationship with Putin means that he would be glad to leverage those threats to pressure Ukraine’s allies to withdraw support allowing for an imposed “fair settlement” in which the invaded country would lose a third or more of its territory and most of its industrial capacity and would be barred from joining NATO or forming bi-lateral military alliances. Under that scenario NATO would be crippled, another long time Trump goal.

Putin has also touted the possible development and deployment of a new super weapon that would make Western nuclear deterrence and the doctrine of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) obsolete sort of like the Doomsday machine in Stanley Kubrick’s How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

The return of a now politically unrestrained Trump means Isreal’s Benjamin Netanyahu will be untethered from any US pressure for restraint and launch long-threatened strikes on Iranian nuclear program facilities and support, a flashpoint for a probably uncontainable broader war.

And then there is Trump’s bromance with the unpredictable Joker in the deck Kim Jung Un of North Korea whose erratic behavior and threatening bomb and medium and intercontinental missiles gave previous President’s fits.

All in all despite the well-meaning Treaty an adjustment closer than ever to midnight on the Doomsday Clock is in the offing.

Protestors at the White House demanded the US sing the Treaty.

The future of real nuclear elimination lies with the people of the world who could launch a major international uprising if annihilation once again overtly threatens us all.

No comments:

Post a Comment