| Richard Fariña |

It

hardly seems possible now but 50 years ago tomorrow, April 30, 1966 Richard Fariña hopped on the

back of a friend’s motorcycle for a quick joy ride in the middle of a party

celebrating the publication of his first novel and his wife’s birthday. Only 29 years old, he was one of the most promising young writers and musicians in America. A

few minutes later he was dead.

That kind of tragic

early death has made legends and

cultural icons out of figures like James

Dean. But despite a devoted

cult following, mostly associated with the fans of his sister in law

Joan Baez and wife Mimi Fariña, his star has faded. Which is too bad. He was a very talented man who led the sort of swashbuckling life that should have attracted a lot of attention.

Partly his obscurity

lies in his own vagueness on the details of his biography. As an artist, he felt free to invent himself and he often confabulated real experiences with romantic extrapolations from their possibilities. He was not the first to do so. Ernest

Hemingway built a Nobel Prize winning

career convincing his readers

that he was really the hero of some

of his most famous novels. Woody

Guthrie’s “autobiography” Bound

for Glory was really a novel

about a character named Woody

Guthrie. Fariña’s friend and contemporary Bob Dylan re-created himself chameleon like until

there was almost no remaining connection

to Bobby Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minnesota.

This is what we think we know.

Fariña was born on March 8, 1937 in the Flatbush

neighborhood of Brooklyn, a stew of ethnicities. His father was Cuban and his mother Irish.

He would build a mythos on both of

these heritages. In childhood

he spent some summers with his father’s family in Cuba. He made his

first trip the British Isles, and his mother’s Ulster in 1953

while still in high school.

Back in Brooklyn, the boy was a star pupil in the Catholic and public schools he attended. In

January of 1955 he graduated from the elite Brooklyn Technical High School,

where he was President of the General

Organization which directed all extra-curricular

activities at the school, Chief

Justice of the Student Court, and had his own column in the school

newspaper.

Returning to Northern Ireland Fariña

became in some way involved—and may have even joined—the Irish

Republican Army (IRA). He may, or may not, have taken part in active operations in the

IRA’s low level guerilla warfare

against the British “occupation”

of the North. He incorporated

the experience in short stories he promoted as autobiographical.

With the help of a prestigious Regent’s

Scholarship—a full ride—he attended Cornell University. At

the urging of his father he began engineering

studies but quickly grew bored and switched to an English

major. He was crafting short stories and poems as an undergraduate as

well as being a part of a thriving

literary community on campus that included his closest friend, the future novelist Thomas Pynchon.

In his junior

year Fariña made national headlines

when he was charged with riot in a student protest against restrictions on female students led by

his friend Kilpatrick Sale. Despite what Sale considered peripheral involvement, he became the face of a minor cause célèbre

when 22 students were placed on trial by

the school. Eventually he and Sale were “paroled” and allowed to remain

in school.

Although Fariña returned to Cornell for

his senior year, he dropped out in

1959 before graduation. His college life, however, became the fodder for the novel Been Down So

Long it Looks like Up to Me.

After leaving school, he took another trip to his

ancestral Cuba, then on the cusp of revolution.

He soaked up the atmosphere and aura of intrigue in Havana and may have even made contact with and done some minor collaboration with revolutionary cells in the city.

Soon back in New York he took a job offer as a copywriter at the top advertising agency in the city, J.

Walter Thompson. Was he “selling

out” or just following the familiar

career path of some of his literary heroes like F. Scott Fitzgerald?

No matter. He was soon bored, restless, and alienated. He started to submit his stories and poems to literary magazines.

Previously a jazz aficionado, Farina began

to haunt bohemian Greenwich

Village and particularly the rich, socially

conscious folk music scene that seemed to be staking out a new cutting edge in American culture. The legendary White Horse Tavern was

a special haunt. There he fell in with the Tommy Makem and

the Clancy Brothers. He was particularly close to the Northern

Irishman Makem, with who he would drink

and sing all of the old rebel songs.

Within a very short period of time he was drawn into the world, if only on its periphery. He gave up the lucrative advertising agency job and

was soon scrounging with the rest of

the Village Beats.

| Carolyn Hester. |

In 1960 he re-connected with beautiful folk

singer Carolyn Hester, then a leading

star of the folk-revival scene

who he had first encountered during a drunken evening of rebel song with Makem

at the White Horse the year before. After an intense 17 day courtship the two married.

Without a job Fariña appointed himself Hester’s manager.

What many saw as a loving collaboration,

others viewed as his crude cashing in on a meal ticket.

Although not previously a performer,

he soon put himself of stage between her sets reading his poetry

with a brooding intensity. He was present in the studio when Hester recorded her third album with the then virtually unknown Bob Dylan sitting in on mouth harp. It was

the beginning of a close personal relationship with Dylan and his set.

Legendary Appalachian traditional folk artist Jean Ritchie introduced him to the simplest of all folk instruments, the three string mountain

dulcimer. When he and Hester briefly took up residence in Charlottesville, Virginia to study traditional music, Ritchie gave

him a dulcimer of his own. Soon he was sitting up on stage with Hester accompanying her on the instrument and

occasionally singing harmonies.

The couple toured

widely in the United States and then in Europe, particularly Scotland

and the British Isles. He got

himself co-billed with Hester at the

Edinburgh Folk Festival and separately

recorded a four song EP with the popular Scottish duo Rory and Alex McEwen

despite having barely mastered his

new instrument. Hester grew increasingly

resentful of his relentless

self-promotion and intrusion

into her career.

After he met the beautiful 16 year Mimi Baez, sister of rising folk star Joan and openly flirting with her at a summer picnic with fellow musicians in

the French countryside, Carolyn abandoned her husband in Europe, returned to the states to record a new

album without him, and filed for a hasty

divorce.

The affair

between Fariña and Mimi blossomed despite an eight year age difference. Mimi’s stunning beauty and the Latin/Celtic

heritage they shared—her father was Mexican and

mother Scottish—had him hooked on

her. His charm, intensity, and way with words won her heart. The couple was secretly married in Paris, without

the knowledge of her family because of her youth.

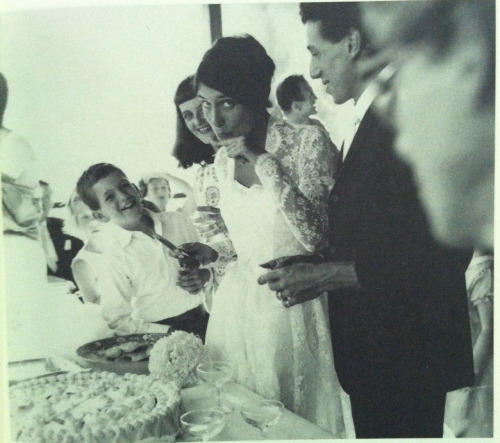

|

| Mimi and Richard on their wedding day. |

They publicly married in April of 1963 with Pynchon

as Fariña’s best man and Joan and

the Baez family in attendance. By that time Mimi was just 17. They set-up housekeeping in California’s

Big Sur in picturesque Carmel

near Joan and began on collaborating

on new songs for a stage act and recordings. Mimi wrote the melodies, sometimes with her sister,

and he wrote the words, some of them adapted

from previous poems.

This time spent in California, along with frequent trips back to New York where

the couple immersed themselves in the circle around Dylan and Joan, was filled

with hours of music. Jamming regularly

with friends and honing his craft.

Fariña was becoming the musician he only

pretended to be with Carolyn Hester.

All this time he had also been working his novel

and getting his stories published in increasingly

prestigious magazines.

The young couple debuted their act as Richard and Mimi Fariña at the Big

Sur Folk Festival in 1964. Their ecstatic

reception there won a contract

with Joan’s record label Vanguard.

They recorded their first album that fall with the help of old friend, guitarist Bruce Langhorne who

had worked with Dylan.

Awaiting the album release they played the folk circuit around Cambridge and

Boston that winter where they became favorites for their unique blend of

Appalachian inspired songs, lyrical expressions of ecstatic joy, death obsessions, and strong protest music.

| Celebrations for a Grey Day, Richard and Mimi's first album. |

The album, Celebrations for a Grey Day,

was released in April of 1965. Surprisingly, almost half the songs on the

album were instrumentals which showed off how he had advanced on his simple

instrument and learned to weave it

with Mimi’s supple guitar work with unique rhythms. Songs on the

album include their most familiar tune, Pack Up Your Sorrows, the

more complex Reno, Nevada, Richard’s ballad of Civil

Rights martyrs Michael, Andrew, and James, and the title song.

Although folk music was being eclipsed on the radio and

in many college dormitories by the British

Invasion and rise of a new,

sophisticated form of rock and roll, Celebrations for a Grey Day was

a solid hit among folk fans. I

owned a copy and it was among half a

dozen albums that I nearly wore out.

Richard and Mimi became true folk music super stars with their appearance at

the Newport Folk Festival. They won awards in a Broadside magazine poll in three

categories—Best Group, Best Newcomers, and Best Female

Vocalist.

Those were heady days. Richard felt he had

finally won recognition after years

of struggling in artistic obscurity.

They quickly began work on a second album, Reflections

in a Crystal Wind. This album was even more ambitious, and featured much more of

Richard lyrics. Memorable songs included Chrysanthemum, Sell-Out

Agitation Waltz, Hard-Loving Loser, House Un-American Blues Dream, Miles, and

Children of Darkness. It was, quite simply, a masterpiece.

Fariña announced

a reduction of public performance to concentrate on writing, both music and

finally finishing the manuscript of Been Down So Long it Looks Like Up to Me

with which he had been struggling

intermittently since 1961. But he had new-found confidence in himself as a writer, not just a character in the role of a writer.

His new fame also assured that major publishers would be interested in the manuscript. He completed a final draft in six intense

months of work and Random House picked

it up.

No comments:

Post a Comment