On October 13, 1792 the cornerstone of the President’s Palace was laid in the virtual wilderness of the Federal

District designated as the future Capitol

of the infant United States. President George Washington was in the temporary

capitol of Philadelphia and did not

dignify the occasion, as he had when the cornerstone of the Capitol Building was laid by presiding

in his Apron for a full Masonic ceremony. Indeed there was no ceremony at all.

With the cornerstone in place the

workforce of mostly slaves hired

from their Virginia masters, Black freemen from the Georgetown area, and a handful of immigrant artisans began digging the foundations. Few

American citizens with full rights were ever employed on the

project which took eight years to complete at a cost of $232,372—$ 2.8 million

in 2007 dollars. To save money, common brick was used to line the exterior walls which were then faced by

sandstone blocks. The stone masonry was largely the work

of Scottish craftsmen employed by

the architect, Irishman James Hoban.

Irishman James Hoban, architect.

Although some interior work

and details remained unfinished, the house was deemed habitable

when the Capitol was transferred to Washington

City. President John Adams and

his dismayed wife Abigail officially

moved in on November 1, 1800, just days before the election that would

send him packing the next year and leave the building to his archrival,

Thomas Jefferson.

Jefferson, an amateur architect of some accomplishment, may have had mixed

feeling about the building himself. He

had anonymously submitted one of

nine designs competing for final selection for the building. He was disappointed when Washington selected

Hoban’s design.

Of course, that competition would

not have been possible without the delicate political maneuvering that located the future capitol city on the

banks of the Potomac instead of the

bustling commercial centers of New York

or Philadelphia.

It

was also a tribute to the enormous prestige and influence of the

first President. The authority to establish a federal

capital was provided in Article I,

Section Eight of the Constitution,

which designated a “District (not exceeding ten miles square) as may,

by cession of particular states, and the acceptance of Congress, become the

seat of the government of the United States.”

In what later

became known as the Compromise of

1790, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and Jefferson with

the benign approval of Washington, came to an agreement that the federal

government would assume war debt

carried by the states, on the condition that the new national capital would be

in the South. The precise location, personally selected

by Washington, was designated in the Residence

Act on July 19, 1790.

Washington

commissioned French military

engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant to lay

out the future city. He envisioned

the spokes-of-a-wheel plan with

broad ceremonial avenues and the

Capitol Building and President’s house on opposite ends of one such grand boulevard.

At the site

selected by the President, L’Enfant sketched in the footprint of a truly grand palace on the European scale for the President. His building would have been five times

larger than the one that was eventually built.

Those plans quickly proved to be impractical—both too expensive

and too difficult to acquire the necessary amount of building

stone. It was also politically unacceptable to those who demanded that the new

government be housed in edifices of sensible republican simplicity.

As Secretary of State, Jefferson

advertised the architectural competition which he entered anonymously. The final selection was to be made by the official

commission overseeing construction of public buildings in the new capital,

but in fact it was Washington who personally selected the design submitted by

Hoban.

Hoban was one

of the few—some say the only—trained architects in the county. He had emigrated from Ireland after the Revolution

and first established a practice in Philadelphia. But after moving to North Carolina, he began to get commissions for important public

buildings, like the Charleston County

Courthouse which Washington saw and admired on his presidential tour

of the Southern states. He personally

invited Hoban to submit a design to the contest.

For

inspiration, Hoban drew on the Georgian country

houses of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy

and particularly on Leinster House,

the Dublin seat of the Duke of Leinster and destined to become

the home of the Irish Parliament in

the 20th Century. Despite winning the competition, Washington

demanded substantial changes from his architect. He ordered the elevation changed from three

to two floors, but that the dimensions of the building be expanded by 30% and

include a large ceremonial space for balls and public receptions—the commodious

East Room. Hoban’s surviving

drawings reflect these changes—the originals submitted for the competition

having been lost.

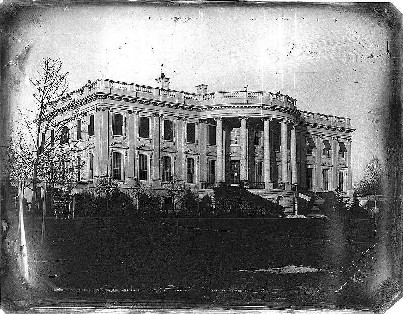

Upon completion

the porous sandstone was sealed with

a whitewash consisting of a mixture

of lime, rice glue, casein, and lead.

This belies the popular story that the building was only painted white to cover the scorch and smoke damage from the burning of Washington by the British during the War of 1812. Informal

references to the building as the White

House have been found as early as 1811.

It is possible that the original whitewash was fading or dirtied

by the time the British put a torch to the building. At any rate, the fresh white paint

applied during the restoration undoubtedly contributed to the informal use of

the name.

Jefferson rejected the name Presidential Palace preferred by Adams as too aristocratic. Under his administration it was commonly simply called the President’s House and for the next century the house was officially named the Executive Mansion. Theodore Roosevelt changed the official designation to the White House in 1901.

The building

has undergone many modifications over the years, starting with the colonnades that Jefferson had

constructed out from each side of the house to screen the stables, greenhouses,

and domestic outbuildings—including slave quarters—from view from Pennsylvania Avenue. The south

portico was constructed in 1824

during the James Monroe

administration and the north portico

was built six years later. Both followed

plans originally drawn by Hoban.

In 1881 Chester Arthur ordered a significant remodel of the building’s interior. Theodore Roosevelt added the West Wing, which his successor William Howard Taft expanded, and the Oval Office was added.

Herbert Hoover added a second floor to the West Wing following a

fire there and added extensive basement

office space for an expanding staff. Franklin Roosevelt moved the Oval Office to its present location by

the Rose Garden. Harry Truman added the still

controversial balcony to the South

Portico.

During Truman’s

administration the building was found in danger of collapse from neglect. The President moved to near-by Blair House for two years as the

interior was gutted and reconstructed. In 1961 First

Lady Jacqueline Kennedy began her interior restoration of the

building to its French Empire

inspired appearance during the later Madison and Monroe years.

The White House

now routinely undergoes modifications with the coming of each

administration. President Barack Obama ordered the instillation of solar panels

to replace those put up by Jimmy Carter

and taken down by Ronald Regan. His wife Michelle

built extensive vegetable gardens

on the grounds which had not been used for agricultural

purposes since sheep were kept browsing the lawn. Of course, among the former Resident first fits

of spite and revenge was to

remove the solar panels and obliterate the gardens. He also trashed up the interior with his

beloved gaudy gold bling wherever he

could, and Melania famously maimed the Rose Garden.

Joe Biden has so far been too busy undoing the

Cheeto’s disastrous policies and trying to get his ambitious agenda through

Congress to spend much time re-doing the official offices and dwellings beyond hanging

and displaying art and making the private residence rooms more modest

and comfortable.

There is continual

work expanding or improving the vast

underground complex that now extends below much of the White House lawn and

houses offices, communications centers,

and, reportedly, a hardened bunker

capable of withstanding a nuclear attack.

But the core of the building remains as Hoban and Washington imagined it more than two hundred years ago.

No comments:

Post a Comment