The modern era of passenger jet travel was inaugurated with great celebration on May 2,

1952 by British Overseas Airway

Corporation (BOAC) on its long London

to Johannesburg route. They were flying the De Havilland DH 106 Comet.

It was an aerodynamically sleek

aircraft with four powerful turbojet

engines buried in the root of its swept back wings near the commodious

fuselage. It carried 36 passengers

with plenty of leg room and reclining seats for the long flights

arranged four abreast with a center aisle. The lucky passenger could view the world far

below them through large, square windows.

Soaring above the clouds and foul

weather that conventional propeller driven airliners had to fly

through, the flight was remarkably smooth. And quiet. Despite early fears that the jet engines

would be loud, their configuration actually made them quieter

than the four heavy engines on most long distance air liners—and with less vibration

for the passengers.

The United Kingdom was fairly

bursting with pride at the achievement. They had beaten the Americans whose major aircraft companies were either tied up with military

production or complacent with the newest generation of prop

planes—the Douglas DC-6 and Lockheed’s mammoth Super Constellation—and perhaps even more satisfactorily the French who were dithering with their own plans.

The country was ready for some good

news in those days. The post-World War II years had been very tough. Much of its industrial production was damaged,

outmoded, or so long converted to military usage that transition

back to civilian production was hard. The

second consecutive generation of young men had been decimated

as casualties of war. Labor

discontent was rife.

Pridefully, the country had declined

to participate in the largess of the American Marshal Plan which was rebuilding

much of shattered Europe, including former foes Germany and Italy.

West Germany was quickly resuming its place as a center

of heavy industry and advanced engineering. Italy was rising on the strength of

extraordinary forward thinking design that was pleasing consumers around

the world. Britain slogged along.

Worse, its far flung Empire was unraveling. India,

the crown jewel, was already gone.

The protectorates in the Middle

East, and their vast oil reserves lost and dominance over Egypt was swept away by Arab Nationalism. Unrest and simmering

revolt stewed in Africa. Winston Churchill had returned to 10 Downing Street vowing, “I did not

become Her Majesty’s First Minister to preside over the dismemberment of the

British Empire.” But, of course, he did.

So, the success of the Comet was

looked on as a sign the Britain was resuming her place at the head of nations

in industrial and commercial development.

The Brits got a head start of

jet production because even as the war was raging. The Brabazon

Committee was charged by the Cabinet

to plan for the nations post-war civilian aircraft needs. By 1944 the

Committee had placed the highest priority on the development of a high

speed “mail packet” capable of carrying at least a few passengers and crossing

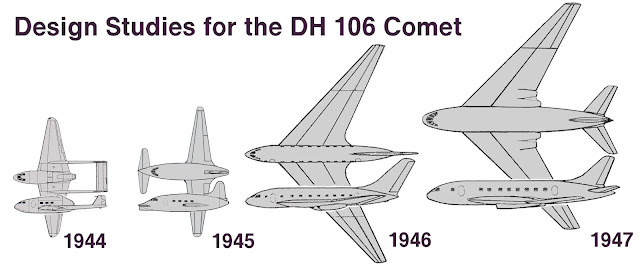

the Atlantic nonstop. Over the next

several years conceptual drawings were made that saw the plane grow from

a small twin tail boom craft to a

much larger, radical design with delta

wings and no horizontal tail

stabilizer. A prototype of

the latter was ordered for testing in 1946 but proved unstable. Some engineers wanted to continue to pursue

that path, but available jet engines were not deemed powerful enough.

Instead, the committee and De

Havilland settled onto a more conventional swept wing design originally

intending it for 24 passengers. As

prototypes of that plane began to be tested in 1949, it was decided that improved

turbojet engines could accommodate a longer body.

The resulting DH-106 model went into

commercial production in 1951 with pre-orders from BOAC and British South American Airways with

several other prospective customers in the wings if commercial service

proved profitable and successful. By the

end of the year orders were pouring in from France other European countries,

and Canada. At least three U.S. carriers pre-ordered

planned second or third generation Comets with expanded

passenger capacity.

But thing soon began to go sour. Within the first year there were three accidents

resulting in the loss of aircraft.

Two of them were failures on takeoff resulting in no loss

of life, but the third, a new Canadian Pacific Airlines Comet 1A, failed

become airborne while attempting takeoff from Karachi, Pakistan,

on a delivery flight to Australia on March 3, 1953. The aircraft plunged

into a dry drainage canal and collided with an embankment, killing

all five crew and six passengers on board. The Canadian Airline immediately canceled

its order for more planes, as did other carriers in a crisis of confidence.

|

| Investigators piecing together of the wreckage of the Karachi crash. |

The British government and De

Havilland launched a desperate investigation. After running down several false leads,

it was discovered that the then little understood metal fatigue had caused catastrophic hull failure. Specifically stresses at the corners

of the fuselage’s signature square windows caused cracks to develop.

The discovery was so sensational

in Britain that No Highway in the Sky, a popular novel and a film

starring James Stewart, Marlene

Dietrich, and Glynis Johns was

based on it. The pleas of the

company kept the plane in the movie from being a jet.

By 1953 the redesigned Comet 2

with round portal windows and other improvements was

introduced. It severed without the same

troubles and got orders. Two more basic

versions were introduced culminating in the Comet 4 in 1959 capable of

carrying 99 passengers. That version

remained in commercial service until 1997 and military reconnaissance

versions were flown by the British up to 2011.

But the Comet, whatever its virtues

and they were many, never really recovered from the stumble out of the

starting gate. It introduction spurred

American competitors into high gear in developing their own planes.

The Boing 707, which most Americans will swear was the first

jetliner, went into service with TWA and

Pan AM in October 1958 followed by

the Douglas DC-8 a year later in

service with United and Delta.

Together they and their successor aircraft would dominate Western

long range civil aviation for two generations.

One possible niche for the

smaller Comet 3 to be adapted as a short and medium range jet liner was

cut off when French Sud Aviation put

their revolutionary Caravelle with

its rear mounted engines into production in 1959 with first sales to Scandinavian Airlines. Soon they did what De Havilland could

never accomplish—sell planes to an American carrier when United Airlines

ordered 200 of them.

You might wonder about my interest

in an aircraft barely acknowledged on this side of the puddle. It might be because it was the first of many airplane

models I ever built as a boy in Cheyenne

who used to watch United DC-8s and Caravells practice take-off and landings on

the long runway of the airport which ran just behind my house.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment