Monday and Tuesday were

the coldest days in the Chicago area in this not-so-terrible winter. After a significant but hardly record

breaking snow over the weekend, skies cleared and the thermometer

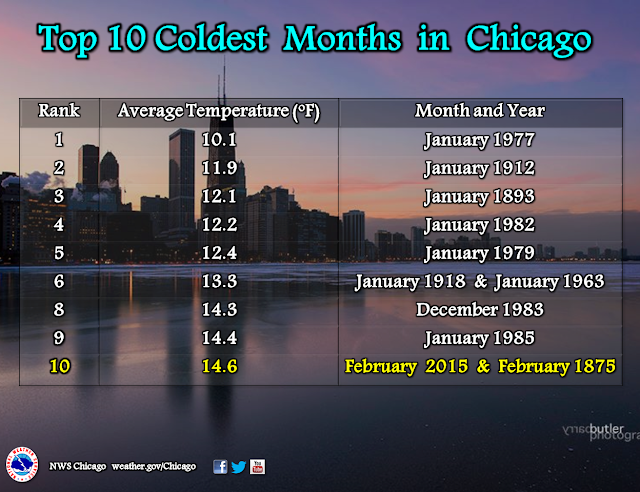

dipped below zero at night and just above in the day. Some TV meteorologists compare to

record shattering the cold snaps like the one in the days before Christmas in 1983 when the lowest day time high temperature of

-13° was recorded on December 24. The

days immediately before were nearly as frigid. And therein lays a tale.

Kathy

and I were living on the first floor of a graystone two flat on Albany Street

half a block north of Diversey with our daughters Carolynne age 13, Heather age

9, and not-quite four month old Maureen.

On

December 20 Kathy asked me to check up on her grandmother Helen Zgorski. Neither she nor her Aunt Benita had been able

to get her on the telephone to discuss Christmas arrangements. Kathy had been calling hourly and was getting

frantic. She called me at work to ask me

to check up on her. I could drop by the CHA senior housing

building on Sheffield just north of Diversey.

That was easy enough. I worked at

RaySon Sports on North Lincoln Avenue repairing football shoulder pads just a

couple of blocks away. I could pop in

before I took the bus home.

The

last of winter daylight was fading rapidly when I got there and took the

elevator to her floor. I knocked on the

door. There was no response. I knocked again. And again.

Alarmed, I went for the building manager who came with me to unlock the

door. Inside, lying on her bed was

Grandma. She was stone cold dead. My heart sank.

We

called 911 to report the death and I waited for the police and paramedics to

respond. Then I had to call Kathy at

home to break the news. She in turn

notified her mother Joan Brady, who everyone called LuLu, up in Round Lake and Aunt

Benita Wilczynski in Chicago.

I

stayed in the small apartment for a couple of hours as the paramedics examined

the body and the police investigated the scene.

Suspicious of the hippy looking guy in a cowboy hat, I was questioned

closely about who the hell I was and why I was trying to gain entrance to the

apartment. I had no way of proving I was

a grandson in-law. I’m sure they called

in my State of Illinois ID card—I didn’t have a driver’s license—and turned up

my arrest record for keeping a disorderly house when a fracas blew up at the IWW

hall while I was Branch Secretary, a disorderly conduct arrest on a strike

picket line at the Three Penny Cinema, and, oh, my conviction for refusing

induction into the Army during the Vietnam War.

That did not exactly endear me to the cops. Finally, while searching the rooms some

photos turned up of Kathy and my wedding and other family events. I was somewhat reluctantly off the hook.

Benita

and Uncle Al arrived on the scene after a while. I blocked her from the bedroom and seeing her

mother’s body. It wasn’t a pretty sight

They

brought her body down to the ambulance for the ride to the morgue. Benita and Al gave me a ride home. We arrived well into the evening.

Helen

Zgorski was a tiny, frail looking woman who could be sharp and abrasive. She was born in Chicago I 1907 to Polish

immigrant parents. Her mother operated a

bakery on North Ashland Avenue near Belmont.

She grew up as a first generation bi-lingual and often had to translate

for her parents. The family was, of

course, deeply Catholic and loyal Democrats, then nearly inseparable Chicago

Polish identities. As expected she grew

up, married, and had two children, Lulu and Benita.

But

her husband died in his 40’s leaving her a widow with two girls. That’s when her connections to the old Democratic

Machine paid off. George Dunne, who was

then 42nd Ward Alderman and would go on be the longtime President of the Cook

County Board, and Cook County Democratic Chairman after the death of Mayor

Richard J. Dailey, found Helen a patronage job as a housekeeper at the old Chicago

Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium.

As a

struggling single mother she was stern with her two daughters entering their

teens which affected her relationship with both.

She

retired from the Sanitarium after twenty years or so. When I first met her she was living in a

small rear apartment in a frame building not far from her daughter Benita and

her husband Al. She would attend family

functions, including frequent Sunday dinners at our Albany Street apartment. After dinner there would be card games—nickel

31 and Uncle Al and I would sometimes try to match her shots of Christian

Brother’s Brandy.

For

a few months she took care of Carolynne and Heather when they got out of St.

Bonaventure School. They would ride the

Diversey bus and walk the couple of blocks to her apartment. Kathy often worked late at her job at Recycled

Paper Products so I would come to get them after my work and walk them the five

or six blocks home.

Preparations

for Christmas were put on hold as the family attended to the flurry of arrangements

that a death always set off. Lulu,

Benita, and Kathy did most of the heavy lifting. There was a funeral home wake which I must

have attended but don’t remember.

Meanwhile

Chicago temperatures were plummeting from merely standard cold to arctic.

On

the day of the funeral mass and burial dawned well below zero with cutting

winds. Baby Maureen was also sick—too

sick to be taken out in the cold. Kathy

told me that I would have to stay home with her while everyone else went to the

services and the traditional after burial restaurant meal with family and other

mourners. Since I had found the body, I

felt somewhat invested in the whole thing and protested resulting in kind of a nasty

spat. But in the end there was no real

alternative. I stayed home.

By

afternoon Maureen’s temperature spiked dangerously and was very sick. In those bygone days before cell phones there

was no way to reach Kathy or any of the other family members who by that time

were at the cemetery. I called the family

doctor and was told to get the baby in right away. On a workday there were no neighbors I knew

who had a car. Cab company dispatchers

could not even promise a pick up in a sketchy neighborhood to go a handful of blocks. Taxis could make all the money they wanted in

the Loop and lakefront neighborhoods.

There

was no choice. I had to carry Maureen to

the doctor. I dressed her in her warmest

onesie, pulled on her hooded snow suit, mittens, and wrapped her face in a scarf. I swaddled her in two baby blankets. And over the whole cocoon put her into a

hooded blanket of brightly colored strips that Kathy had knitted and woven

together.

Maureen

might have been well insulated, but I was not.

I had my long johns on, of course, a plaid flannel shirt, jeans, and slick

soled cowboy boots. My winter coat, blanket

lined denim with a corduroy collar like those worn by railroaders was fine in

ordinary cold but was way too thin for the below zero weather and stiff wind. On my hands I had canvas and leather palmed

work gauntlets pulled over thin brown jersey gloves. At these temperatures my fingers were frozen

in moments. I tied a red bandana around

my ears and pulled my old Stetson down tight.

It

was not far to the doctor’s office. Just

south on Albany a couple of blocks to Logan Boulevard, over the wide parkway to

the other side and another couple of blocks to the office near the intersection

with Milwaukee. But it was face-freezing

cold and snow blowing from rooftops stung.

I was most worried that I would slip on sidewalk ice or trip over the

rock-hard piles left by snowplows at the end of each block. It was a moustache freezer. Each breath was like a knife to the lungs. We

were probably outside less than 15 minutes, but it seemed infinitely longer.

The

doctor’s office was not crowded. Few

patients had ventured out in the weather.

Cooing nurses helped unwrap Maureen’s many layers. In fact, the baby may have actually been

over-heated by the bundling. She was

crying, fussing, and very flush. Her

face was almost burning to the touch.

The receptionist got me a hot, bitter cup of office coffee in a

Styrofoam cup.

Youngish

Dr. Findlay Brown saw us almost immediately.

He was the family doctor and had treated Kathy and the girls for some

time but barely knew me. He was caring

and concerned. He quickly ruled out the

most frightening childhood illnesses. He

wrote a prescription and gave me advice about how to cool her down at

home. He also said in no uncertain terms

that I was not to carry Maureen home.

The sun was going down and temperatures were plummeting again.

I

picked up a prescription at the small pharmacy that served the medical

building. It turned out that the druggist

used to own the drug store my family used in Skokie when I was in high school. We chatted a bit. I tried again unsuccessfully to call a

cab. I left Maureen with the nurses in

the office while I went out on the Milwaukee Avenue side of the building to see

if I could flag one on the street. No luck.

I

considered the CTA, but I would have to wait with Maureen for a Milwaukee Ave.

bus and then transfer to an east-bound Diversey Bus. Waiting for the busses could easily take

longer than the walk. I still could not

reach Kathy or Uncle Al who had a car.

An

hour or so after the appointment, I spotted a police car at the stop light on

Milwaukee. I ran up and tapped on the

window. It was a two-man squad car. Both cops were relatively young. I explained my situation and practically

begged them for a ride home. Despite my

disreputable appearance they agreed and waited while I ran in and re-bundled

Maureen. We arrived home about 5pm and I

was profuse in my thanks to the cops who had ignored rules and procedures for

us.

A

while latter Kathy and the older girls arrived home. I was scolded for taking Maureen out into the

dangerous cold.

The

next day her fever broke. Christmas came

despite it all.

I’ll

save the tale of losing our heat and our pipes bursting in another record

shattering cold snap in 1985 for another day.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment