Oppenheimer may be eye opening for generations for whom nuclear catastrophe seemed a distant possibility.

Note—The recent release of the highly praised film Oppenheimer must be a thunderbolt for the two, maybe three generations who grew up without the daily dread of imminent nuclear annihilation. This blog post, first appearing in 2012, looks back at growing up expecting to die in a nuclear war.

August 6 is always, inevitably, the day a city full of human beings was obliterated by the first use of an atomic weapon. No matter what else happened on this date, it is always Hiroshima Day.

I don’t think my daughters’ generation, or my grandchildren have any idea how we were shaped and warped by the long shadow of that mushroom cloud. To those of us who came into awareness in the years after The Bomb was dropped and as a Cold War heated up nuclear war, seemed as inevitable as Christmas. Maybe more so.

I don’t mean to whine about it. The school children who were burned into shadows in Japan and those who somehow survived with the long, lingering pain of radiation poisoning were the real victims, not the privileged kids of the people who unleashed the power of the sun in the air over a city going about its mundane business. Our nightmares and little terrors were of little consequence by comparison. Perhaps they were no more than we deserved.

After years of being rolled back after the end of the Cold War and the adoptions on new international arms control agreement, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has re-set their Doomsday Clock back to where it was in the early and dangerous day of the nuclear arms race due to saber rattling by North Korea and Israel, the possible construction of an "Islamic Bomb" by Iran, and recent threats by Russia during its war in Ukraine.

In 1953 we had recently relocated to Cheyenne, Wyoming. My twin brother and I were four years old. I, at least, was becoming aware of the world in odd ways. My mother, who had grown up in grinding poverty even before the Great Depression, was star struck by the new pretty young Queen Elizabeth, who had just been coronated with all of the pomp the British can muster, which is plenty.

Our coffee table was littered with Life, Look, The Saturday Evening Post, and other magazines that captured the details of the fairy tale event. I loved those pictures and my mother’s excitement over them. But on the back pages of those same magazines were pictures of mushroom clouds and worried looking men in uniforms.

About the same time, we got our first TV set and a signal could finally get to Cheyenne, relayed by microwave towers, from Denver. There were three hours of snowy TV a day and twenty-one of a test pattern with an Indian head in the middle. We would stare at that pattern waiting for the shows to come on. Mostly 15 minute musical programs, boxing three nights a week, Milton Berle, and I Love Lucy. But there was news, too. Mostly a guy who looked like an insurance salesman reading behind a desk. One in a while a picture would loom up behind him. Very often it was one of those daunting mushroom clouds.

Who knows how the mind of a curious four year old works? I do know that the first dream that I ever remembered—and snatches of it are vivid in my mind to this day—involved the pretty young queen in her fairy tale coach, that ominous cloud, and rockets going straight up and then coming straight down on the other side of a river. And I was on the side of the river they came down on.

A year or so later we moved into an old house on Bent Avenue just a few blocks from the state Capitol building. It had a nice, big backyard with trees, a row of old lilac bushes that formed wonderful caves, and a little lean-to shed by the garage that we made our playhouse. To add to the wonder, my dad brought home a loading palate and put it up in the spreading branches of an ancient plum as a tree house for us. He put up a railing around it and nailed boards to the trunk to help us climb the maybe three or four feet to where the branches fanned out to nestle the platform.

He imagined that we would play Cowboys and Indians there, then our main pastime. But I immediately had another use entirely for it. I scrambled to find the toy binoculars that I had gotten at Frontier Days. And then I made it my job to climb into that tree house every day and scan the sky with those binoculars…for Russian bombers. And I did it every day for most of the summer, not just for a few minutes, but sometimes for hours.

This is a map of likely top Soviet nuclear attack targets during the cold war. Note the huge black blob covering Cheyenne, Wyoming and adjacent Nebraska and Colorado. Although this map dates to the 1980's after Francis E. Warren Air Force Base added scores of underground ICBM missile silos over hundreds of square miles, we were just as central to Russian plans when there were a couple of dozen above-ground Atlas missile pads clustered more tightly around the city.

In 1958 Cheyenne’s Francis E. Warren Air Force Base became a Strategic Air Command (SAC) post. Over the course of two years 24 Atlas Intercontinental Ballistic Missile launch pads were built scattered over the Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska plains around the city. It became the first operational ICBM base in the country in 1959.

It was cause of considerable local pride that because of these missiles, Cheyenne had become one of the Top Ten Nuclear Targets in the event of what seemed to be an inevitable war with the Soviet Union.

By this time, we had moved out to a new ranch style house near the edge of town along the long runway of the airport. We went to the recently constructed Eastridge Elementary School. Across the road from the school was a large vacant track filled with tumbleweed, thistle, and button cactus. We called it a prairie.

In most schools across the country children hid under desks during bomb drills. At Eastridge Elementary we were sent to a vacant field to lie down among the tumble weeds and cactus to wait for the nuclear blast to "roll over" us.

More frequently than we had fire drills, we had air raid drills. In some places children were taught to cringe under their desks. But since we were so close to the primary blast zone, that was thought to be inadvisable. Luckily, we were told, we had the field right across the road. In case of an air raid, we were instructed to file calmly out of the building, cross the street, and lay down in the weeds with our hands clasped behind our heads. We were not to look up or move.

When the bomb would go off, the theory was, that the power of the blast would “roll over” us and we would be safe from collapsing buildings. I wondered, lying there one day as ants crawled up my legs and began biting me in unpleasant places, wouldn’t the fire ignite the prairie and roast our supine little bodies?

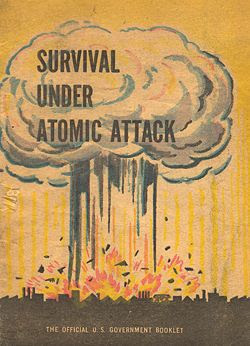

I became obsessed with nuclear war as the Cold War heated up to a fevered pitch. By the early ‘60’s I had gotten caught up in the fallout shelter craze and was unsuccessfully begging my father to build our own bunker in the back yard. Failing that, on the very day President Kennedy announced the Blockade of Cuba in 1962, I was at the Wyoming state Civil Defense headquarters scooping up preparedness pamphlets. I even devised a Civil Defense plan for Carey Junior High School, which, much to my own surprise was adopted by the school and even used district wide. They didn’t have anything better. The authorities probably knew we were all doomed anyway and that playing at preparedness would make the kids feel safer.

I collected and studied intently pamphlets and brochures like this from the Civil Defense office.

What does it mean to grow up with that level of intimate involvement with the shadow of the bomb? It would take a team of psychiatrists to figure it out.

Eventually it made me into a guy who very much wanted to stop that war…and any war that might lead to that war…before it ever happened.

No comments:

Post a Comment